BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

In the first of a series of articles on jobs within the religion sector, Robert Golding delves into how Anglicanism has coped during Covid-19

If you visit the Reverend Alison Joyce at the famous Wren church of St Bride’s just off London’s Fleet Street, there’s a decent chance that she’ll take you into the hub looking out onto Salisbury Court.

There you’ll find a stone memorial to a woman called Mary Ann Nichols, who is best known as one of Jack the Ripper’s victims. Bespectacled and intelligent – one of those Oxbridge-educated reverends who is also a theologian – Joyce points it out as I’m leaving. “It’s one of the things I’m most proud of. If you read the history books she’s a victim – but she was a member of this parish and we still owe her a duty of care.”

The plaque is moving. But you have to be here in Wren’s famous space to feel its full force. That’s true also of the memorial to journalists who have lost their lives the world over – among them James Foley and Clive James.

All our services have gone out online. Since March 2020, we’ve never missed a service. We can do that because we have an amazing choral tradition.

The Reverend Alison Joyce

“Covid has impacted on every aspect of our life as a church,” Joyce says. “The most challenging aspect has been the pastoral one. You add the Covid restrictions in a ministry where touch is very important – you need to be able to hold someone’s hand. We are a sacramental church which means things like communion are very important.”

The Biblical phrase which is most applicable to the pandemic is that which is supposed to have been uttered by Jesus upon his resurrection: ‘Noli me tangere’ – do not touch me. It’s still not clear why he says this, whether it is a warning of the physical ramifications of touching him – or as theologians might say, touching his ‘risenness’ – or whether to do so might be to incur some strange and insupportable physical sensation.

What’s certain is that the church has had to operate for the last year without touch. Like museums, they’ve been sent online; also like cultural institutions they’ve found a global audience which they might not have expected to encounter.

Joyce explains St Bride’s pivot to online: “All our services have gone out online. Since March 2020, we’ve never missed a service. We can do that because we have an amazing choral tradition. And of course the lovely thing about that is, we’ve got people contributing to those services internationally. There’s one woman who does readings from the States – so actually we’ve got an amazingly global congregation.”

So the Anglican church, which stretches back to the marital woes of Henry VIII, cannot avoid the need to think about tech provision. Last summer I visited St Lawrence’s in Ludlow and found myself immediately accosted by a warden extolling the virtues of the church’s new app. At St. Lawrence’s if you point at the famous misericords with your phone, you’ll see them flicker into interactive life: a medieval woman cooking, a knight galloping towards you.

During the pandemic, I’ve often found myself wondering about those medieval structures which I most came to mind about in the days when going to them was part of a typical calendar year. Durham cathedral, my vote for the most beautiful building in Europe, where the remains of St Cuthbert are buried, at time of writing lies numerous Covid tiers away.

Interested to know how they’re doing, I catch up with Charlie Allen, the residentiary canon at the cathedral to find out how things have been. The cathedral also moved to online worship, and now has, according to Allen, “a global community of prayer of 340 members.” (It is a feature of writing about the Anglican church that the numbers discussed can seem heartbreakingly small).

That’s all well and good, but central to Christian experience for thousands of years has been the Eucharist. Allen concedes the problem: “It has been impossible to engage with the subtleties of the Eucharist in this way. The touch of a wafer and the taste of wine cannot be communicated in digital form.”

“The touch of a wafer and the taste of wine cannot be communicated in digital form”

charlie allen, residentiary canon at durham cathedral

Even here Allen remains optimistic in a way which might help us all in our strange locked down lives: “We are looking forward to being able to gather physically again, but we are also aware that having to withdraw from contact for so long has heightened our senses and given us a deeper appreciation of that which we have missed.”

It might interest readers to know how many job opportunities there are in the Church, even during an era of apparently declining belief. That’s partly because the decline takes place against a backdrop of extremely high belief: Christianity remains the religion of the nation, even if church attendance is extremely low. Locally, it’s a part of the fabric of life, even if it is beset by indifference during a time when there is so much else to claim our attention. According to the Faith Suvrey, church attendance has declined from 6,484,300 to 3,081,500 for the period between 2008-2020. And yet as the state has shrunk, the church has sometimes rushed in to fill the void.

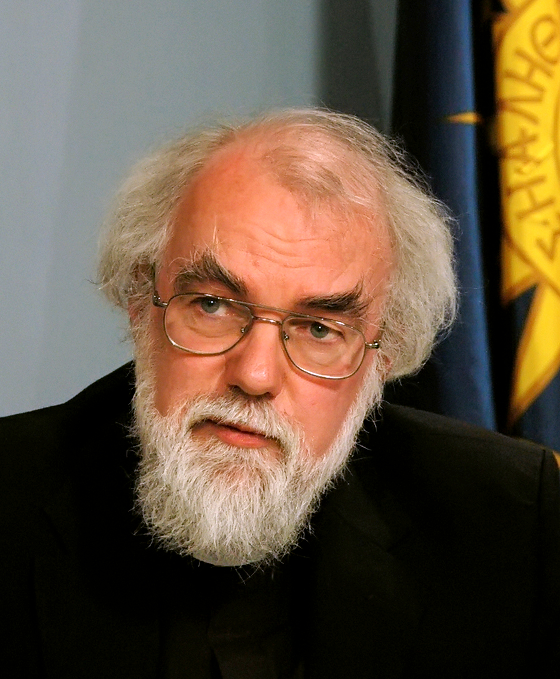

This author recently visited the home of the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams who joked that he had ‘made it big’ in the church, while making me a Nespresso.

For instance, the Church Times still has a jobs section which shows a lively number of options for people wanting to be involved. It might even be crudely said that it’s still possible to achieve stardom of a kind. This author recently visited the home of the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams who joked that he had ‘made it big’ in the church, while making me a Nespresso. His house was a vast receding grace-and-favour home round the corner from Magdalen College, which he would leave shortly after. Russian Christian art hung from the walls, and Williams’ study was jammed with books.

We talked about the low attendance at typical London church services, and he alikened the church today to those early services during the time of Paul of Tarsus, where meaning was arrived at not just in spite of sporadic attendance, but partly because of it.

“We have catering jobs, housekeepers and hospitality staff, education, facilities management, members and retail: there’s a considerable range of jobs for the laity”

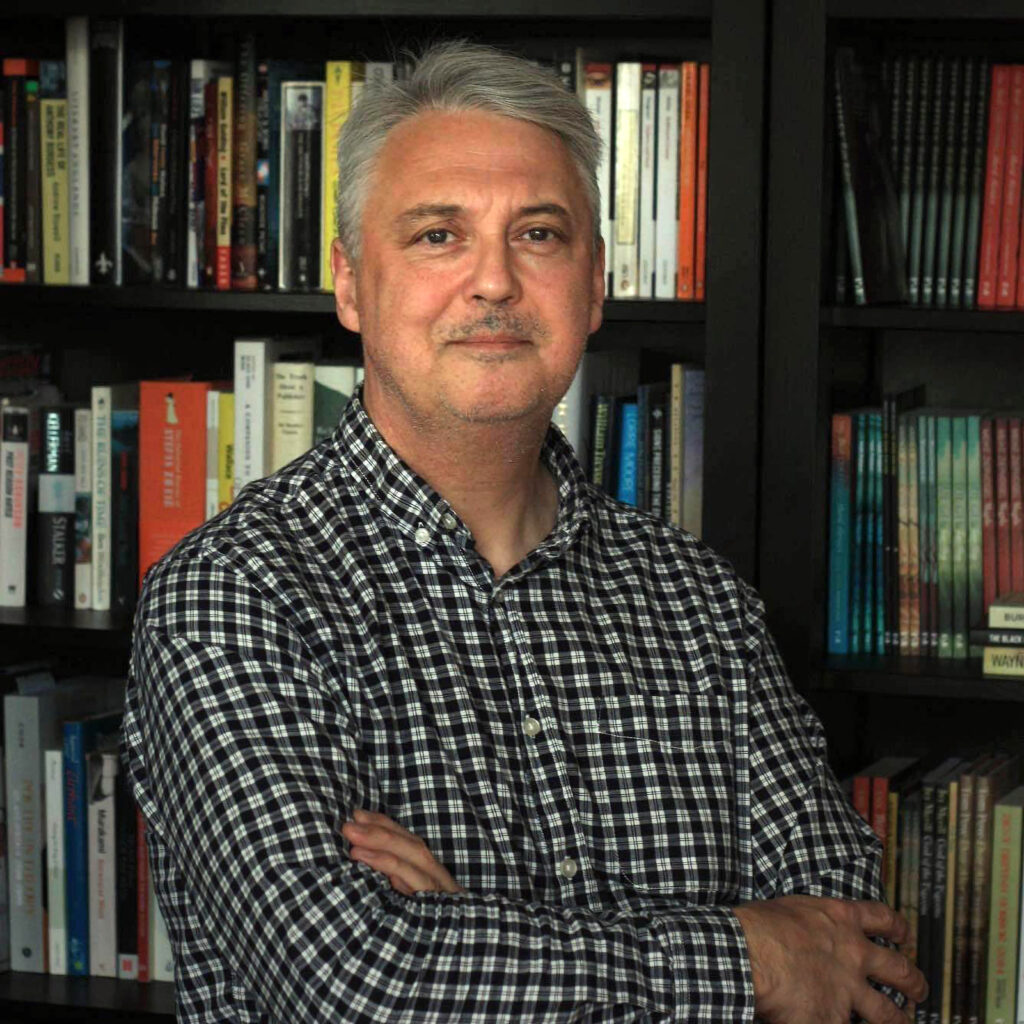

christopher hamilton-emery

Williams’ point may ring especially true during Covid, where people are especially searching for meaning. And if it does strike a chord in students, then job opportunities are there. “As a cathedral we have a team of paid staff, and an even more extensive team of volunteers,” Allen explains. One interesting figure who recently joined the ranks of the church is the great publisher and poet Christopher Hamilton-Emery, whose brilliant poem ‘And Then We’, which we reproduce opposite, celebrates his change of career.

Hamilton-Emery explains to me how he was “dislodged from my own [secular] convictions”. His role at The Shrine of Our Lady of Walsingham is a reminder that there are many roles available outside the route of taking holy orders. “At the Shrine, we have catering jobs, housekeepers and hospitality staff, education, facilities management, membership and retail: there’s a considerable range of jobs for the laity,” Hamilton-Emery tells me. “The Church has a lot to gain from experienced general managers coming into serve – so I hope people, even people with no faith, can see that the Church has lots to offer society and can come in and help develop businesses.”

And what traits are required? “You don’t need to believe, but you do need to sympathise. You need empathy with the aims, you need to accept moral goodness and love (which may strike some as odd). But most of all you have to care for people and to put the human at the centre of everything you do.”

That might appeal to some at a time when we’ve seen retired GPs volunteer to administer the vaccine, as well as an increase in people applying for nursing qualifications.

Of course, the career you have will depend on the locality of the institution you end up at. Joyce’s ministry at St. Bride’s is highly unusual, with a small residential population, which in usual times would predominantly serve commuters. This segment evaporated overnight in March 2020. “We have a very different community to serve from somebody in rural Oxfordshire or a parish on the outskirts of Birmingham,” Joyce explains. “We’re also lucky because obviously it’s a famous building and we’re also famous for being a journalist church. That in itself makes it an international ministry.”

Pre-pandemic I would give out between 10-20 food parcels and fuel card top-ups per week…We are now giving out 150-200 per week

The Reverend catherine shelley

Things are somewhat different for a nearby ministry run by Rev Dr Catherine Shelley – that of St Edward’s in Mottingham, in Kent, on the borders with south-east London.

This is a more impoverished area – but also in a suburban part of London where footfall has increased during coronavirus as more people work from home. Shelley implemented an unexpectedly eclectic online programme: “Karate and taekwondo, Zumba, dance and Slimming World have all been able to go online, though personally I cannot do Zumba online!”

However, the impoverished conditions of her parishioners differentiate Mottingham from Joyce’s parish, and from the wealthier area around Durham Cathedral. “A lot of the congregation and community do not have internet access,” Shelley explains. “One third do not have email and local schools are still using booklets for remote learning as families cannot access online provision. The circulation of sheets has increased from 55 at the start of the pandemic to over 100 paper copies and we also send out over 50 by email to those who are online. Some of the increased circulation is to families we have known previously through sporting and social activities in the church hall; some of it is to families we have come to know through the ever-expanding foodbank.”

We all have a role to play in healing and recovering and seeking forgiveness. It’s a moral failure if we don’t do this within society.

christopher hamilton-emery

It’s the food bank which has really taken off. “Pre-pandemic I would give out between 10-20 food parcels and fuel card top-ups per week,” Shelley continues. “We are now giving out 150-200 parcels per week. We have also prepared regular hot meals for some who struggle to cook, collected medicines, shopped for those shielding or self-isolating, provided access to IT to support job searches, benefit applications and advice, IT access for virtual court hearings, housing support and so on… We never really know what is going to be asked next.”

It is impossible not to admire the sheer range of the church’s response – after hearing from Shelley, the church appears far from a quaint and marginalised aspect of our societal fabric. It feels integral.

Eve so, Shelley is more pessimistic than Joyce, Allen or Hamilton-Emery about the financial position of many dioceses: “There have been rumours of significant cuts in clergy posts – with some mention of a reduction of 20 percent but it is too early to say what the picture will be across the country,” she says.

How does she think it will play out? “It will vary from diocese to diocese because each diocese is a separate charity, with differing resources and priorities. It is suggested that some are in a precarious position financially so more mergers, such as happened in Wakefield, Bradford and Leeds a few years ago, appear likely.” And what’s the prognosis in London? “One thing that will make a difference is the exodus of families from London. I am aware in my own area in South East London, that some parishes are losing up to 20 families who have decided to re-locate outside London because of the possibilities of home-working or due to redundancy. That will probably have a larger impact on church and diocesan profiles and jobs than the pandemic itself.”

And if working in the church isn’t of interest, what does it have to teach us at this time? All those I spoke with for this piece felt that there was great meaning to be found in lockdown – and everyone agreed that there would be a revelatory atmosphere in the world once restriction are lifted.

Hamilton-Emery is optimistic for the future: “We all have a role to play in healing and recovering and seeking forgiveness. It’s a moral failure if we don’t do this within society. I see this as an opportunity of unity and reengagement rather than fracture and dissolution.”

Over at Durham, Allen seconds that: “The pandemic has invited each of us to face up to our own mortality, and to the mortality of those whom we love. Rather than making us morbid, my experience has been that this has given people a fresh appreciation of all that they value in life.”

That rings true. It may be that the Anglican church, far from being irrelevant, is about to find itself more relevant now that people have been given time to pause and consider the direction of their lives. Reality, it turns out, has a way of impacting on us, even if we can’t touch one another. Perhaps somewhere in there is the true meaning of that mysterious phrase: Noli Me Tangere.

And Then We

And then we embraced, sprawling on the green deck like scattered gulls.

And then we knelt under bound flax sail cloth, stinking and making the day.

And then we carried whom could not stand to the red chapel blithely.

And then we walked through your pristine marsh without hours or love or trees.

And then we drew about us buckram cloth and wool dyed with kermes and slept.

And then we pierced cockleshells and yearned for a tangled feast of eels.

And then we walked by sordid wolves and boars in corporal torment.

And then we met with hirsute leather brigands and were lost.

And then we starved, Lord, and knew concupiscence, gnawing your works.

And then we heralded salt wind, seal routes and spectres and walked dully on.

And then we saw your slipper chapel and spread our toes on a mile of stones.

And then we wept. At the ruin of our bodies we wept. At our just ruin.

And then we dressed and swayed, all the same, through the unifying street in a love queue.

And then we bent and entered Nazareth to see her and to know her choice.

And then we knew a high permanent land, our eyes fixed on accommodating angels.

And then we fell in stone-sealed Walsingham, with our fiat ringing, unanchored, teeming.

And then we left to see ice oak burials, flame drift farms, our backwards night talk blazing.

And then we sailed on, working new bones, each a prayer to the star of the sea.

--Christopher Hamilton-Emery