BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

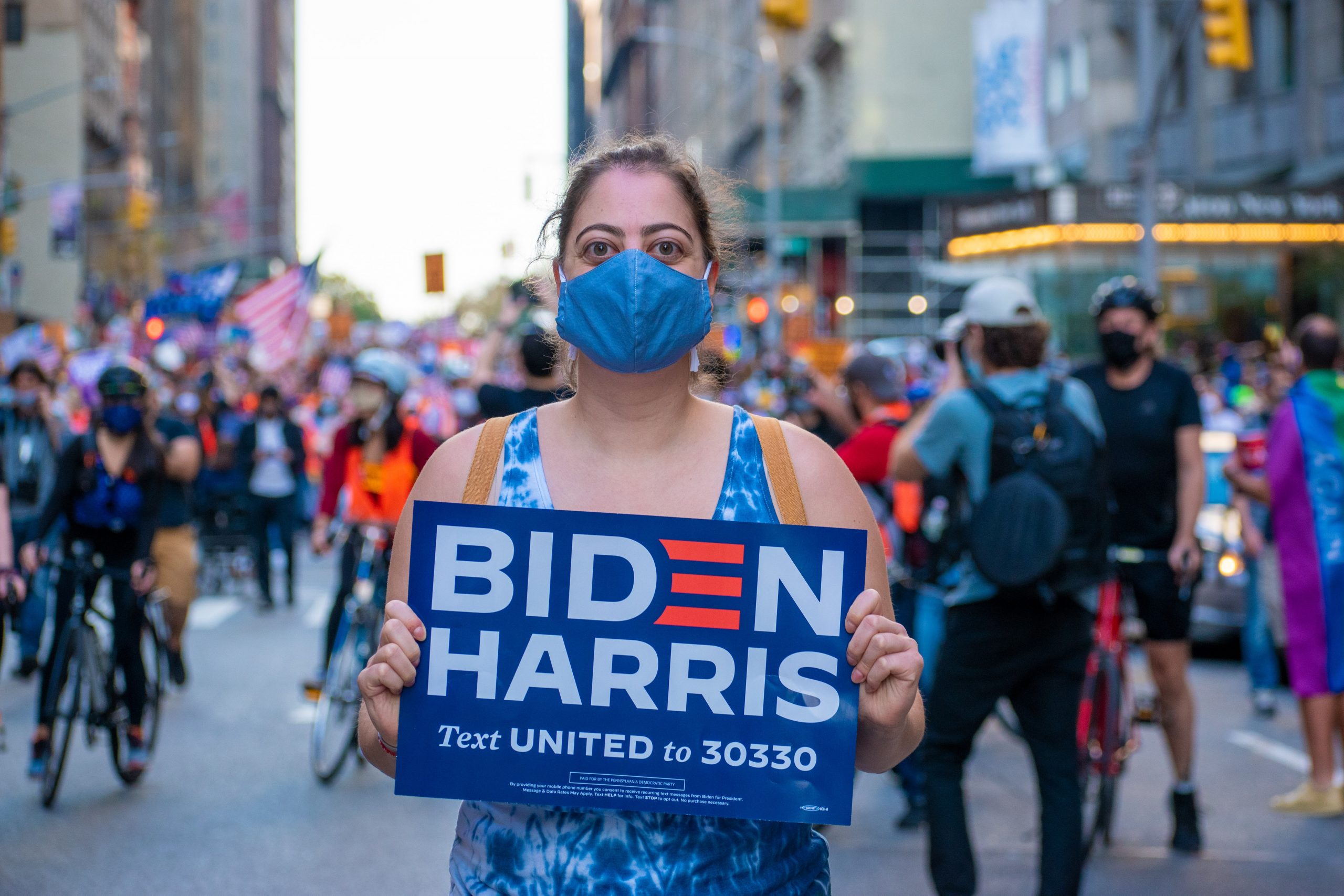

Young people and experts on climate change, diversity and arms sales reveal the significance of the new Biden administration for the UK

Georgia Heneage

There has been much hype around what the new Biden administration signifies for a politically divided country infected with issues of social inequality, racial injustice and a deadly virus which has killed over a million of its people.

In his first month in office, Biden seems to have already conducted (or at least promised) a systemic upheaval of many of the unpopular and controversial policies in place during the Trump administration, such as its sceptical approach to climate change, immigration and foreign policy. With Kamala Harris as the first female vice president of colour, there is a new mood around questions of diversity and inequality which were largely ignored under the Republican regime.

But the impact this seismic shift for America will have on the UK is yet to be seen: will it really be that seismic? And, if it is, will the effects be negative or positive?

The view of those working in these key areas in the UK is that the large scale shake-up which Biden is promising should urge us to follow suit, but the likelihood that it will is less than certain.

‘We want to fight for change’: the view of the young

For 21 year-old Connor Brady, Staffordshire University’s Labour Student’s society manager, the “tone” and “conversation” in the UK changed immediately following Biden’s inauguration.

Though he is unsure that “policy-wise” much will change in America for young people, Brady believes that Biden’s environmental policies will play a large part in emphasising the UK’s thin approach to climate: “His new policies highlight the fact that we’re not really having that discussion in the UK. I don’t think that we are going to make the changes necessary to save the planet, whereas in America the thought process is at least there”.

The fault, says Brady, lies with a media system in the UK much less attuned to climate worries than across the pond, and a political culture “defined by indecision”.

“I’d love it to be the sort of example that we’d follow,” says Brady, “and say that we need to take it seriously because they are. But I don’t think we really have a political class that are ever going to really take notice of the way other countries are doing better: we’ve seen it with Covid.”

Staffordshire’s society’s communications officer Jagdeep Jhamat, 20, said Biden and Harris’ appointment was “a sigh of relief; the moment we found out the results we realised that a saga had just ended in American politics, and it was not a good one”.

For Jhamat, though, the appointment of Kamala Harris does not signal a substantial benefit for people of colour in America or the UK. “Just because she has credentials of being the first woman of colour doesn’t excuse the fact that she was a judge who sentenced people of colour to prison with insufficient evidence. It’s not the best representation of minorities in America.”

And Jhamat sees a parallel in this respect with UK politics: “I have nothing in common with ethnically ‘diverse’ MPs like Rishi Sunak or Priti Patel: all I see is them selling out to the interests of a ruling white international capitalist class.”

Despite this, Connor Brady says the Black Lives Matter protests which started in America last year had a hugely positive affect on young people in the UK who are increasingly “politically disenfranchised”.

“The movements that we’ve seen over the past year have shown that young people are ready for change, and they are going to fight for change,” says Brady. “They aren’t going to wait five or ten years. They are willing to stand up and say no: we need change now, and we’re going to take it. That’s what I’m really excited about.”

His worry, though, is that “if Biden and Kamala don’t follow through on their promises, or if their policies aren’t radical enough, then it’s going to increase the disenfranchisement of young people in the UK who look up to them”.

‘Embarrassment is a useful tool’: Natalie Bennett on environmental policy

One of the areas most transformed by the Biden administration to date is his climate policies. After years of climate denialism and environmental destruction under Trump, the White House has now recognised global warming as an “emergency”: they’ve rejoined the Paris accord, promised new opportunities for clean energies and green technologies, and signed an executive order to freeze new oil and gas leases on public lands and double offshore wind production by 2030.

These are just a few of hundreds of ambitious executive decisions established in an effort to position climate change as an essential part of all American foreign and domestic policy going forward.

Biden’s extensive environmental policies show his awareness that beating climate change requires systemic change; a scooping out and refilling of the American economical and political systems rather than a sprinkling on top.

So where does this all leave the UK?

For Natalie Bennett, former leader of the Green Party from 2012-2016, Biden’s appointment signals a golden age for the global fight against climate change.

More importantly, she says it puts a huge amount of pressure on the UK as the chair of COP and highlights what a mess the UK is in. “Embarrassment can be a very useful tool”, says Bennet. “If a country like the USA, which has so many similar problems to us like poverty, inequality and the dominance of giant multinational companies, are doing better than we are, that makes us look really bad.”

Bennett says the US’ Green New Deal is far more sophisticated than the Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution announced by the UK government in November last year.

“The Biden administration has come in with a very clear plan of action on whole areas of key policy, whereas our plan looks like something written down on the back of an envelope then hastily sketched up into something. It’s not long-term thinking,” she said.

Bennett sees these issues with making long-term executive decisions in the UK as part and parcel of a binary, first-past-the-post electoral system which means that “we are terrible at decision-making”, and the “last significant change in Westminster was women getting the vote 100 years ago”.

It’s also down to our deeply centralised political system, where power and resources are concentrated in Westminster and local government’s ability to make independent decisions has been “slashed to ribbons, to the point where most local governments have their hands tied”. Bennett says the rhetoric of the Green New Deal is, by its natural structure, locally based: it’s about doing things in communities, whereas “our industrial strategy is about what the top level decides and what companies invest in.”

Despite the UK government’s promise to create 250,000 jobs in the green sector, Bennett says Biden’s new policies are far more rooted in a recognition that climate change should be rooted in the labour movement, technological progress and job creation. His “just transition” policy “suggests change everywhere”, whereas in the UK there’s a sense that everything needs to level up to the status quo set in London.

“What we are talking about here is business as usual with added technology. Biden is talking about transformation,” says Bennett.

Lee Pinkerton on Kamala Harris and diversity

One of the most predominant issues brought to the international stage last year was racial injustice: these were voiced in mass Black Lives Matter protests which started in America, a country for whom racial discrimination is a daily reality for millions and is deeply embedded in the political and justice system.

Biden’s appointment signals a shift in this area, partly because of his pledge to tackle social and racial inequality in America, partly because of the sheer weight lifted by expelling a president who many deem openly racist, and partly because America is now enjoying the first woman of colour as its vice president.

Though some see Kamala Harris as an exciting new change in political black representation for women, Lee Pinkerton, communications officer for ROTA (Race on the Agenda), a leading social mobility think tank, agrees with student Jagdeep Jhamat that Kamala Harris’ appointment will “in truth have very little real effect on people of colour around the world”.

“They had a short feel-good moment, but it will have very little real impact on the quality of black people’s lives in America in terms of things like employment or criminal justice”, says Pinkerton, “especially because Harris wasn’t all that popular among black communities when she was a judge”.

In the UK a similar kind of “superficial” diverse representation can be seen in government. “The Tories are boasting of the most racially diverse cabinet in UK history- which is factually true- but it hasn’t improved things for black people at all. If you look at the back story of MPs like Home Secretary Priti Patel or Chancellor Rishi Sunak, they come from the same privileged, privately-educated backgrounds as their white peers. They are cut from the same cloth, and in terms of diversity of thought- there’s little to none”.

‘Our blind spot’: arms sales to Saudi Arabia

The ethical, political and economic impact of the UKs involvement in the war in Yemen, in part a result of us being the second largest exporter of weapons to Saudi Arabia, has long been a source of controversy.

This week tensions intensified as the new Biden administration announced its intention to freeze all arms sales to Saudi Arabia and work towards a lasting peace agreement to end the war that has now killed around a quarter of a million people and placed at least 4 million on the brink of famine.

When asked its response the day after Biden’s move was announced, the UK government were clear on one thing: they are not going to alter their approach towards selling weapons to Saudis, many of which reportedly end up killing innocent civilians.

The UK’s arms export licensing information reports that licenses worth £5.4 billion for sales to Saudi Arabia have been issued since March 2015, though they also consider this an underestimate. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, since 2015 Saudi has been the largest importer of arms in the world, with the UK accounting for about 15% of these exports, and the US around 75%. Saudi Arabia represented 40% of the volume of UK arms exports between 2010 and 2019.

So will America’s decision to roll back from its heavy involvement in Yemen have any impact on the UK?

For Dr David Blagden, senior lecturer in International Security and Strategy at the University of Exeter, Biden’s decision will “potentially leave the UKs tacit support in Yemen even less tenable”.

But Blagden says following suit may be unlikely, since the key difference between the UKs involvement and the US’ is that, whilst America “is less and less dependent on gulf hydrocarbons and it doesn’t really need gulf oil anymore,” in the UK we still rely on Middle-Eastern oil and gas and have in fact been “doubling down on gulf commitment over the last few years with the new base in Bahrain and Oman.”

Blagden says the UK previously used the US’ involvement in the Gulf as “cover” and because America was so involved the UK didn’t really stand out. “But the US revising its position on that will, I think, produce some even starker tensions for the UK.”

Blagden suggests that our continued support may be rooted in the fact that the arms sales contributes to so many “highly paid and highly trained jobs” in manufacturing and munitions sales. But according to Oliver Feeley-Sprague, Amnesty International UK’s Military, Security and Police Programme Director “the jobs argument is overstated in terms of the impact. Yes of course big contracts would suffer, but in the overall scale of things, Saudi is only one of many destinations we sell to and we’re not talking about stopping every sale of equipment to the Gulf.”

Feeley-Sprague also doubts the validity of the argument that arms sales contributes so much to our economy: “If you look at the economies of scale, the UK is the second largest arms supplier after the United States. But the US is by far the largest: 75% of all weaponry over last 5 years that Saudi has imported in terms of monetary value has come from the USA.

“Yes we are the second, but the US is by far the largest, so if we flip that argument on its head it’s a much more valuable market for the US than for the UK. If the US have said they’ll stop, that puts the UK in a very isolated position”.

Feeley-Sprague says the biggest impact of the US’ decision for the UK will be felt on individual companies: “In a globalised market the arms trade is intrinsically linked to international supply chains. US restrictions will have practical implications on companies reliant on US defense companies for their own sales.”

This should never be a reason not to take the ethical path, though. “We always say you should never allow strategic, economic, political factors to override the pure principles of international law which is the protection of innocent civilians in armed conflict,” says Feeley-Sprague.

For Paul Tippell, Constituency Coordinator for UNA-UK Yemen, the UKs leading source of analysis on the UN, the biggest issue in the UKs position with regards to Yemen is not arms sales but it’s failure to play a part in the ceasefire of a war which has been called the biggest humanitarian crisis of our time.

“Our job is to set the agenda and come up with resolutions; we have a big responsibility and there’s a real opportunity to work with the new administration in the US to try and secure peace. The UK has been singularly lacking in this respect.”

So why have we been so ‘singularly lacking’? Feeley-Sprague says the UK has had a “blind spot” for Saudi Arabia for decades, and are prepared to tolerate more issues than almost any other “customer”, because they are seen as “a key market for money and a strategic partner in the UK’s foothold into the wider region”.

But Brexit has placed the UK in a precarious position on the international world stage, and we must be careful: “If ever there was a way of announcing on the world stage that we were a major power who considered human rights and the rule of law to be important, now is the time.

“Because the UK hasn’t done that, I think it puts a question mark in the post-Brexit role that the UK wants to play in the world,” says Feeley-Sprague.

Brexit and an indecisive government may place the UK in an isolated or precarious position on the international stage, but the entrance of Biden means the return of America as a neoliberal international economy with one eye always turned outwards. It signals a golden dawn, full of hope, for young people.

Gone are the days of protectionism and reckless international policies which governed America under Trump; the age which a new Biden administration ushers in appears to be one of global consensus, free trade and rigorous attention to the key issues. Let’s hope he achieves what he promises to.