BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Joe Biden and the Pitiless Society, Finito World

The question of whether we should feel compassion for our politicians is a complicated one. For some in today’s media, our leaders have surrendered the right to our pity by seeking to rule over us. Journalists talk of ‘holding politicians to account’: it is as if, if they don’t, some inherent venality will suddenly emerge.

Under such a view, without the presence of a harsh media, all politicians will immediately begin to cheat and lie. Hard-bitten journalists therefore have the opportunity to congratulate themselves, after each uncovering of political malpractice, that a form of public service has been undertaken.

We have seen during this election cycle in the UK, with the gambling scandal, that there is never a shortage of people in public life doing silly things. Sometimes, the tone of the coverage doesn’t allow the perpetrators room to express sincere remorse: if they do express regret at their own actions, we will say that we led them unwillingly to that expression.

Perhaps we did. But we must be careful to remind ourselves that we didn’t lead them there necessarily from a superior position. Except for the very few who on this planet may be in a place of genuine enlightenment – and how many of these really are there alive at any one time? – we are usually observing some version of human frailty which we also in some greater or lesser degree possess ourselves.

This is even more the case when it comes to old age. ‘Ask not for whom the bell tolls, it tolls for thee,’ wrote John Donne, for whom the bell tolled, as he had predicted in 1631. His words have remained true ever since.

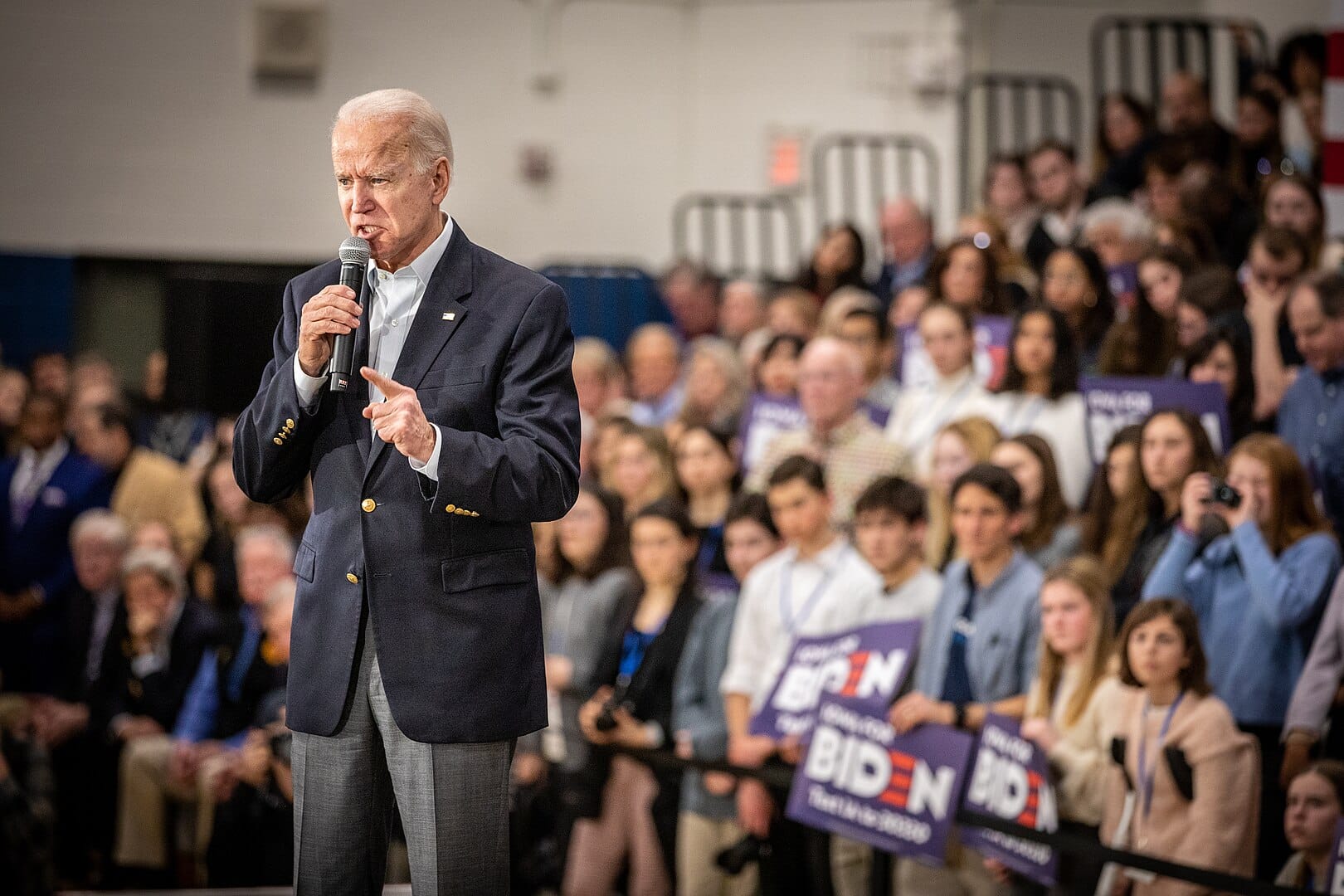

The sight of Joe Biden struggling on stage last night in the First Presidential Debate was a sad one, not just because of the specifics of what he said, or failed to say – but because it is also touches the universal. One day, suddenly or slowly, we shall all find the faculties we had relied upon desert us – and few of us shall be on stage when it happens.

It was heart-breaking to watch. Yet one notes sometimes an air of excited glee in the coverage. “Biden bombs!” ran The Daily Mail headline. “Joe-Matosed,” chipped in The Sun. This is the British media, and a degree of excitement at others’ misfortune is perhaps to be expected.

But interestingly, those broadly on Biden’s side exhibited a similar sort of surprise at the fact that President Biden, like all the billions of people who aren’t president, is also subject to the laws of nature. Here is Chris Cillizza, a pundit on the Democrat-leaning CNN, writing on X: “He looked old. His answers trailed off repeatedly. He was hard to understand. He would stop in mid sentence and move on to something else. I NEVER thought he would be this bad. Stunning. Truly.”

There is a note of amazement here which amounts almost to enjoyment of Biden’s predicament – as if that predicament weren’t also ours. Why did Cillizza never think this would happen? Did he think that Biden, by virtue of being president, had somehow the power to reverse the irreversible?

Sometimes, the mockery of Biden has a sort of worship of power on its reverse side. The implication runs something like this. Doesn’t he know he’s president and that this sort of thing is unseemly? Can’t he sign some sort of executive order against his own decline?

Our surprise at Biden’s mortality shows how disconnected modern Internet politics, and the security state, makes us from reality. Our way of life seems to sever us from compassion because the stage seems so vast and we are perennially cut off from those who take to it.

By seeking to rule over us, Biden has signed up to scrutiny in a whole range of ways. Good journalism is to monitor public life with an air of humility, knowing that we’re seeking to ward off the sorts of faults in our politicians which we also share.

But something changes when we get to a situation like this. It is a moment to pause, and allow ourselves the pity for someone powerful which we have almost come to think we’re disallowed.