Costeau reports on how the cost of living is affecting one of Mayfair’s oldest institutions: the Private Members’ Club

As Costeau walks into 5 Hertford Street, he receives that jolt of self-importance which he has learned to distrust: there is a sense, which surely must be foolish, that one has somehow arrived. Isn’t that Robin Birley sitting over there? Didn’t that tall chap used to chair the Conservative Party? And I seem to remember that woman has a title which she only uses when she comes in here.

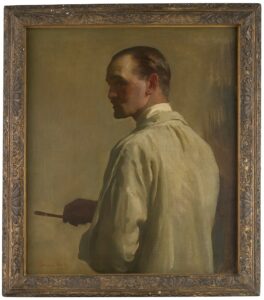

Of course, 5 Hertford Street has an immaculate aesthetic, the bloodline of which one might trace back past Robin Birley, through his father Mark Birley – also the founder of Annabel’s and a myriad others – back to his father Sir Oswald Birley, the middling portrait-painter. Part of its pleasure is the sense of a very plush warren, where some of the most important meetings are taking place in some attic or anteroom whose existence you certainly wouldn’t intuit in the foyer.

Oswald Birley, Self-Portrait

Even so, as nice as it all is, the suspicion remains that people join Private Members’ Clubs not just because they’re convenient, but also to say they’ve joined them. There is perhaps a certain commercial power to saying to a prospective client: “Let’s meet at my club.” This sentence alone suggests the existence of disposable income, and therefore success.

When I speak to an ultra-high-net-worth individual who seems to be a member of almost all the clubs of London, including Alfred’s where the Dover sole is especially to be recommended. “This is my kitchen,” he says, with a gesture at the whole of Mayfair, not referring to one of these clubs, but to all of them.

The job opportunities in these places mirror those in the broader hospitality industry, marrying up the possibilities of working in a Michelin Star dining setting with working in a luxury hotel. One manager tells me candidates wouldn’t stand a chance of success without “discretion, presentability and perhaps a quiet enjoyment of the finer things in life” – even if you are serving people who are experiencing those finer things and not experiencing them yourself.

The expansion in these clubs these past years has meant that it is possible, if you have the income, to be never far from a possible exclusive spot. If you’re somewhat exhausted after a meeting with your banker in the City, then for five years or so it’s been possible to swing by Ten Trinity Square. Here you enter a world of wood-panelled comfort: an experience which ought to rub away at the fact of having spent the morning in a financial institution discussing the interest rate.

While Ten Trinity Square is still relatively new, one of the features of the world of private members’ clubs is to feel a connection with the city’s past – and especially with its aristocratic past. In Home House, there is the magnificent staircase by Robert Adam, spiralling up towards a skylight. The dining room offers expansive views of Portman Square as you eat what may be the best cuisine in the city.

Ten Trinity Square, the go to club for the City

But perhaps there is an increasing sense of disconnect in today’s cost of living crisis. Pampered luxury isn’t always the best look when, a few streets away, others are struggling to make ends meet. If joining one of these clubs is tantamount to admitting to a spare £5,000 a year, one may sometimes wonder if that money might not have been better spent. Many of the members of these clubs publicly remind the outside world that they’re engaged on extensive charitable works after all.

Perhaps this is why I was rather fond of the House of St Barnabas just off Soho Square where the food was so reliably bad as to salve one’s conscience. I say was because news has now reached me that the club has sadly closed, but I think there is much other clubs can learn from the attempt. In the House, the coffee possessed the unmistakeable tang of Nescafé Instant, the pizza – one of the few things on the menu – tended to almost laughably inedible, and even the nibbles could reliably bring on any number of gastric illnesses.

But there was method in this madness, since the place doubled up as a homeless charity. The club’s website tells visitors that the House is on a mission to change the conversation around homelessness, broadening the definition away from rough sleeping to encompass the 104,510 households currently in unsuitable accommodation.

The House of St Barnabas sadly announced its closure in January 2024

Chief Executive Rosie Ferguson explained in the club’s 2023 Impact Report: “Private member’s clubs have existed for centuries. They have often acted as exclusive spaces for the elite, an environment created in order to give wealthy people their own networks and careers, and their exclusivity has been at odds with diversity, inclusion and social progress.” This is an important document – one searches in vain for evidence of 5 Hertford Street’s social impact report. That’s not to say Robin Birley doesn’t do any good – most people do – but The Guardian has reported that staff were lobbying in 2019 for a living wage, with porters paid £8.50 an hour. This report may need to be taken with a pinch of salt, since it was written by that scourge of the right, the left-wing commentator Owen Jones who might be said to have a certain predisposition to paint Birley et al. in a negative light.

But it does make one wonder a bit about the ultimate purpose of these places, even as one always enjoys dining at them. One also can’t help but feel that their original historical intention has been slowly mutated by a failing politics.

These clubs originally emanated out of the coffee shops, and were places of political debate: one has an image of William Pitt the Younger holding court at White’s or Charles James Fox issuing his latest opinions at Brooks’s just down the road. This was not an undebauched time, especially not for Fox who, being the Boris Johnson of his day, was as dedicated a philanderer as he was an orator. But nobody doubts they had concrete matters to discuss.

William Wilberforce, who was in the Pitt set, extricated himself from the club scene after his conversion and the result, after a long period of attrition in Parliament, was the expedition of the abolition of the slave trade. One wonders whether the House of St Barnabas, with its impressive Employment Participation Programme, where 95 per cent of participants have completed the course, might have marked a new seriousness of purpose more suitable for these times. The club had worked with 42 employers, partnering with Bafta 195 and Nimax Theatres. Let’s hope that despite its failure it has some sort of legacy.

Similarly, there has been a marked rise in the women’s only private members’ club, with the Allbright leading the way. This is named after the first female US Secretary of State Madeleine Allbright who once remarked: “There’s a special place in Hell for women who don’t help each other.” Notable members include actress Olivia Wilde, filmmaker Gurinder Chadha, and the business woman Martha Lane-Fox.

All of this shows that the sector is shifting, and that the opportunities for a meaningful career are broadening. This is now an area where you can work in a thoughtful environment as much in the service to ideals, as in the service to ultra-high-net-worth individuals whose opinions you might not agree with. Obviously, if the coffee had been better at the House of St Barnabas that might have helped with the membership numbers; but equally, it might not be an idea for 5 Hertford Street to do a bit of visible giving back to the community.