BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Finito World

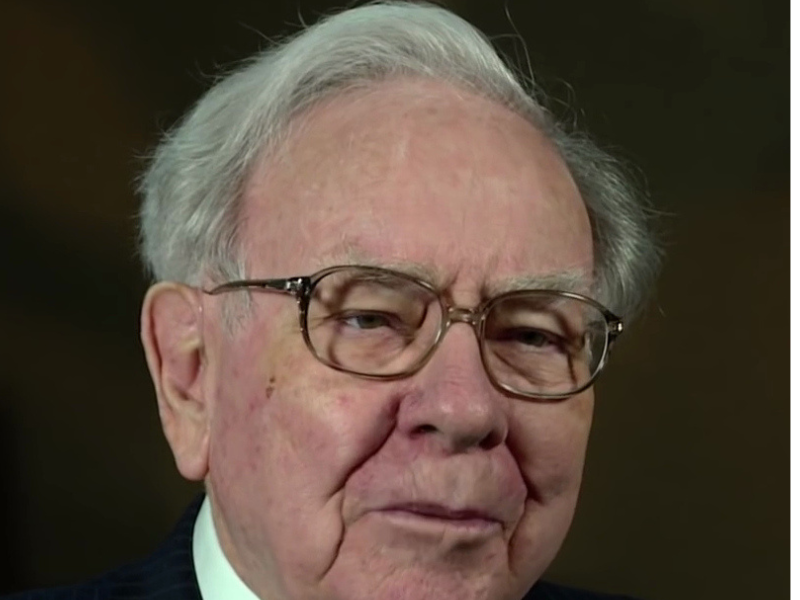

In his final letter to shareholders, Warren Buffett didn’t offer forecasts or grand economic pronouncements. Instead, the 95-year-old investor — writing after nearly six decades at the helm of Berkshire Hathaway — left readers with something more lasting: wisdom.

There was no CEO swagger, no Silicon Valley spectacle. Just a man, nearly a century into his life, reflecting on the strange combination of discipline, loyalty, fortune, and friendship that made Berkshire into a $1.1 trillion enterprise — and him into something rarer still: a capitalist revered for his conscience as much as his compound returns.

From the quiet streets of Omaha to the boardrooms of Coca-Cola, Buffett’s journey has always run against the grain of Wall Street’s usual ambition. It is in that spirit that the lessons from his last letter are best read — not as bullet points to be quoted, but as principles to be lived.

The first is geographical: you don’t need to live in New York or Silicon Valley to build something world-shaking. Buffett never left Omaha. His home, office, mentors, and memories were all within a six-mile radius. His story is a rebuke to the idea that greatness requires migration. For Buffett, roots were not a constraint but a kind of compass. In a world that prizes novelty, he championed familiarity — and bet the house on it.

But that geography of success, he reminded us, was underwritten by luck — the second great lesson of the letter. Buffett acknowledged that he was born with every advantage: male, white, healthy, American, reasonably intelligent. He didn’t sanctify his own rise — he contextualized it. And now, he said, that luck is running out. At 95, banana peels and balance issues loom larger than bull markets. And yet, with characteristic humility, he calls it as it is: “I was late in becoming old… but once it appears, it is not to be denied.”

Still, he argues, age is an asset — to a point. His own successor, Greg Abel, is a spry 63, old enough to know the culture, young enough to lead it. In succession planning, as in investing, timing matters. Wisdom compounds, but so does wear.

Buffett doesn’t shy away from fallibility. The fourth lesson is simple: everyone makes mistakes. He offers no macho myth of infallibility. Instead, he recalls the Coca-Cola fiasco of “New Coke” — and the graciousness with which his friend, then-CEO Don Keough, admitted failure. What mattered wasn’t perfection, but the willingness to admit error, pivot fast, and preserve trust. The market forgave — sales soared.

From there, Buffett’s tone grows more personal. Don’t ruminate, he urges. Learn, forgive yourself, and move forward. That’s lesson five. Then comes six: imagine the obituary you’d like and live to earn it. Not exactly a spreadsheet strategy, but for a man who sees life itself as a form of capital allocation, it fits. Think long-term. Value what endures.

His seventh lesson is moral: be kind. Buffett reminds us that the cleaning lady is as human as the chairman. Greatness, he writes, isn’t money or fame. It’s in helping someone — quietly, consistently. There is a moral economy beneath the financial one, and in that realm, the golden rule beats the golden parachute.

And finally, if kindness seems too ambitious, Buffett offers one final plea: at least don’t be a jerk. It’s a line delivered with a wink, but it carries weight. You can be rich. You can be brilliant. But if you can’t be decent — or at least try — then what’s the point?

This was not a letter about quarterly earnings. It was a meditation on how to live, invest, and lead. As Buffett prepares to leave the office he’s worked in for 64 years, just a few blocks from his grandfather’s grocery store, he offers a kind of American stoicism — one rooted in decency, patience, and faith in people over algorithms.

There will be bigger fortunes (although not many). Louder voices. Flashier letters. But there will never be another Warren Buffett. Not because he was a genius — though he surely was — but because he remembered something so many forget: business, in the end, is personal.

And life, like Berkshire stock, is best judged over the long term.