Cosmo Landesman

My parents had a cabaret club in America in the mid-West. They did plays and had performers – people like Woody Allen, and Lenny Bruce – and a then unknown singer called Barbara Streisand. They put on plays by Pinter and Beckett and had a show on Broadway and moved to London in 1964.

I was too young to remember Woody et al. but I remember going to the club and Albert King – B.B. King’s brother – was there and I went up on stage and did the twist. My Dad went on to do all sorts of things; he was a theatre producer, who put on a play at the Edinburgh Theatre Festival. My mother was a lyricist and wrote jazz songs and became a performing poet.

I think my Bohemian upbringing gave me a taste and a leaning towards the unconventional. I’ve never followed the traditional path of most of my peers. I didn’t go to university and didn’t go to Oxbridge. I dropped out – and hung out.

There are disadvantages to that, and I don’t think it makes me superior at all. It gives me a certain unique perspective and that’s good. That Bohemian tradition of which my parents were part of in the 1960s is something I miss. The classic moan is that Soho isn’t what is used to be. But cities have to change. Soho, which was once the Mecca of the Bohemian, has gone.

But sometimes I look back at people who I thought of as square and conventional, and think of how they have the pensions. When you’re in your twenties, you think: “Pensions be damned!”

I know quite a lot of people who did law, for example, not out of passion or interest, and regret it. I could never do something like that; I’m too dumb. I went into journalism because I was too stupid for everything else. I always wanted to write and I’m happy with my choices. I know plenty of deluded journalists who think they’ll write the great novel. Robert Harris is the exception everybody names. I realised I had no talent in that area; I abandoned all hope!

Fleet Street used to be fun. Last time I went to The Sunday Times office it was like going into a library; it was so quiet and calm. Nobody hangs out and has lunch anymore. I meet young journalists who remember The Modern Review and it seems exciting to them. I was invited by Robert Peston to come to his Academy to talk about jobs in journalism. I would say: “Don’t do it – or only do it if you’re driven by a crazed passion that you must.” It’s a bit like becoming an actor – have a reserve job.

I don’t do the kind of journalism that aims to change the world; I want to make people think, but mainly I want to make them laugh. You just do the best you can do, and pray to God that somebody will be moved. You try to be good and say something original and fresh. 95 per cent of what I read is this sludge of opinion and punditry.

Book-writing is very unlucrative too. If you look at the statistics of the number of writers who make a living from their writing alone, it’s tiny, especially for a country as cultured and book-oriented as the UK. That’s not to say that you shouldn’t write books. It’s very rewarding.

My real advice to young people is to try and be different. In this day and age, there’s such conformity – especially in the mainstream. 25 people writing the Harry and Megan article: do something different even if it will be a bit harder. Don’t follow the herd.

If you devote yourself to journalism and writing, you’ll have what we call cultural capital. Don’t not do it because of fear about your pension.

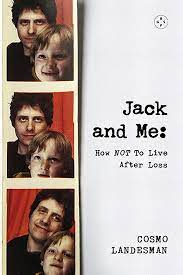

The death of my son Jack, who committed suicide after developing a drug problem, isn’t an easy topic – especially if you’re a parent. Who wants to read a book about this? It came out over the Christmas period last year. I hope people will find in the book more than just a sad memoir. I wanted it to be thoughtful and to have something to say about loss; I wanted it to be entertaining. I wanted to think about what it means to be a Dad.

Parenting is trial and error; you bumble along and try your best. One of the things I write about in the book is that I had this idea of being a great Dad. I realise that I wasn’t being the Dad that my son needed, but I was trying to be the Dad I might have wanted. You don’t have to be a great Dad, you have to be a good enough Dad. You have to show up; you don’t have to be spectacular. It’s not just showing up at the parents’ evening. They’ll remember you sitting you in a chair, and leaning over and smiling at them, and pulling a funny face. It’s those small things: as long as there’s an atmosphere of support, love and care.

You’re going to make terrible mistakes; being a Dad is about being a flawed human being. You’ll shout and lose your temper and regret it. That’s part of the business; it’s what you have to learn.

There are days when I think Jack could have had more support for his condition, but I didn’t give him enough support either.

But I can’t point the finger of blame; these things are complex. You often read that so and so committed suicide because of bullying. I don’t believe that; what drives people to that state of despair is a whole set of complex reasons. It’s not just one thing which does that. We always have these initiatives and drives, but I don’t think there’s a magic wand we can wave. We don’t really know why certain individuals commit suicide. Some will have suicidal thoughts; it’s only a minority will actually go through it.

We need to give young people more tools when they face adversity and unhappiness. Suicide shouldn’t be an easy option; I sometimes wonder it’s become a sort of lifestyle choice – a human right. It should be understood that it’s a terrible thing to do, not just in relation to oneself, but in relation to others. But sometimes the mind orders its own destruction and that’s a scary thing.

The trouble is my son had a terrible drug problem. We’re beginning to wake up to the impact of drugs on young people. I grew up in a generation where drugs were considered recreational and even mind-expanding, and people thought that anyone who disagreed with this view was a right-wing lunatic. Well, that’s just not true.

I don’t think prosecuting people is going to solve the problem. You have to get people to understand what they’re doing. Our drugs problem also enriches the drug dealers, who are the worst in our society.

People feel embarrassed to say they find my book funny, because it deals with tragic things. But humour is important – it’s perhaps especially important here. You don’t have to have a damaged son to enjoy this book.

Jack and Me: How NOT to live after loss is published by the Black Spring Press Group