BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

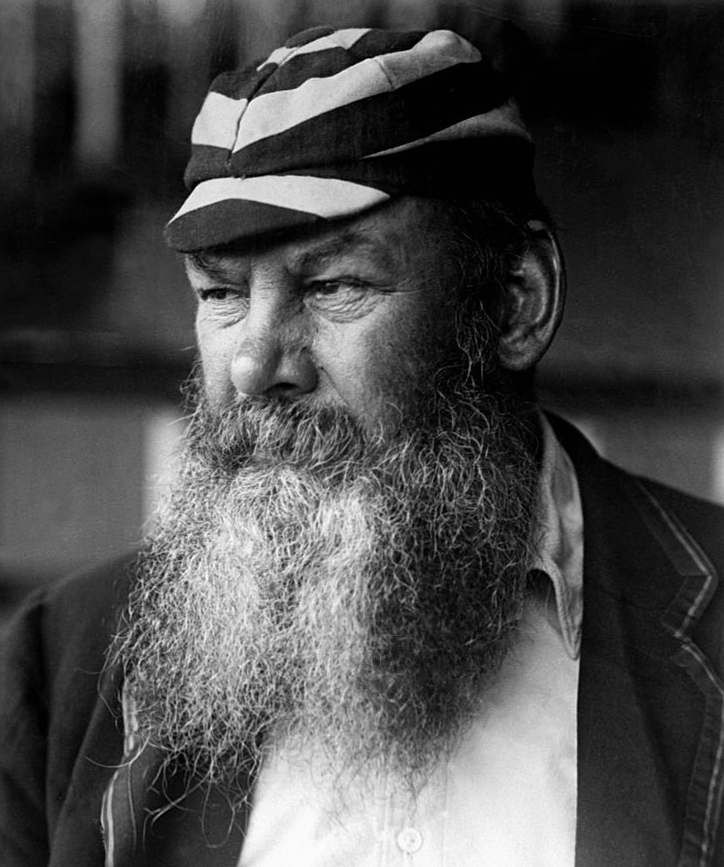

by Robert Golding

In the post-war period, my grandfather used to go to Lord’s and the Oval every year without fail. In his later years – he died in 2013 – he’d tell me about the time he watched the last innings of the great Australian batsman Don Bradman.

As the story goes, Bradman needed to score four runs to finish his Test match career with an average of over 100. He received a guard of honour and the most sentimental version of the story claims that he was still wiping the tears from his eyes when his second delivery by Eric Hollies bowled him. He would finish with the famous average 99.94.

The story is well-known. But what I particularly remember is the civility of cricket as my grandfather recalled it. In those days, if you suspected you had trapped a batsman leg before wicket, you would witness the delivery, mull the possibility of an appeal, and then, on the way back to bowl, politely enquire of the umpire: “How was that?”

In little details like this, we realise how fast the world is changing. Today, a typical appeal will involve frenetic shouting of Howzat!, and an utterly theatrical despair if the appeal is turned down. The way the sport is played today reflects a society which wants it all – and, to paraphrase, that well known cricket fan Queen guitarist Brian May – wants it now.

Our cricket, then, speaks to the society we’ve become. Alongside these developments, cricket has grown exponentially as a professional sport – as every other sport has also done. Many of these activities – including billion-dollar industries like football, tennis and golf – were invented to supply activity to the Victorian gentleman liberated from drudgery by the Industrial Revolution.

Suddenly everyone had a weekend to fill. The growth of village cricket and other pastimes might also be put down to something more mundane: the invention by Edwin Budding of the lawnmower in 1832. This, the year that Goethe and Sir Walter Scott died, feels like one of those hinge years when a whole way of life cedes to another. Without Budding’s invention, the English summer with its sound of leather on willow, its players in cricket whites moving towards the batsman ‘like ghosts’ as the poet Douglas Dunn observed, and its sense of the day unfolding with relaxed culinary predictability – sandwiches for lunch and cake for tea – would have been impossible.

2020 feels like just such another year, and it finds cricket also at a crossroads. Today, if you type the phrase ‘cricket jobs’ into Google, you’ll discover a bewildering array of options – although applying for many them appears to contain the implicit stipulation that the applicant be extraordinarily good at cricket. At time of writing, jobs are already being advertised for player coaches and coaching and talent specialists for the coming season in Australia. Although many of the ads require the applicant to have played at a high level of cricket, most also require significant administrative ability.

In addition, as cricket has become more complex, the number of roles of a purely administrative nature has also increased: ads for operations officers, and brand managers abound. In addition, there’s even an ad for an umpire manager posted by Queensland cricket. The job description explains to applicants that they will need to ‘develop and implement strategies designed to attract and recruit potential umpires across the state’ while also ‘building and overseeing a network of appropriately skilled people who can provide umpire training and assessment.”

The ads in Australia are a reminder of the international nature of cricket, but they also point to the great hinterland of people who are talented at cricket, but no longer able to consider playing professionally. Or perhaps they never were never in the running.

As cricket has resumed, I’ve had a sense that this is a sport peculiarly suited to post-pandemic life. Yes, it’s always been international which rather goes against the grain of our travel-restricted lives this past year. But it’s also one of the remaining sports which are really to do with stasis and patience – qualities which we have been forced to learn during the pandemic.

That’s not all. It was John Arlott who in his great book on Jack Hobbs asked himself what made Hobbs great and decided it was his “infallible sympathy with the bowled ball”. When I mentioned this to Jonathan Agnew recently, he looked delighted at the remark, and nodded vigorously: “Yes, yes, I like that. That’s what cricket’s all about – and it’s also why I don’t like football.”

This opens up onto the essential civility of cricket. It is what makes it, beyond other sports, relevant to our wider lives – including our careers. We wouldn’t speak of the spirit of football, or tennis, or golf: but we can and do talk of the spirit of cricket.

It is, in fact, an essentially democratic sport. For instance, the phrase ‘good cricket’ refers to a passage of play where typically, a good delivery has been bowled, a fine shot made, engendering in return a skilled piece of fielding and wicket-keeping. Usually in such moments, the actual score hasn’t been advanced but something has been achieved by both teams together.

It’s this civility, and undercurrent of decency, which creates a sense of hiatus from the stress of the world, and therefore makes the sport an ideal way to switch off. Sir David Lidington recalls how the sport sustained John Major in his time in office. “To John, cricket remains a great solace, a place where he can switch off, and cares fall aside for a time,” he tells us. Most famously, Major, having lost the 1997 General Election to Tony Blair, declared he was off to watch the cricket: one could feel his delight.

For many of us therefore, cricket has been a dimension almost beyond capitalism, and certainly beyond the cut and thrust of politics. It is this notion of cricket as a protected zone of our lives which accounts for the indignation at the rapid commercialization of the sport, especially by the IPL and The Hundred.

But perhaps we should be careful about saddling cricket with a Victorian flavour forever. Major himself was no classist as Lidington points out: “What was true about John was his absolute commitment to social mobility and loathing of snobbery.” One cannot imagine Major ever minding, say, Ben Stokes’ tattoos; one can only imagine him delighting in his talent.

So now cricket enters a new phase, where an international test championship hopefully heralds the beginning of a new purpose for cricket. It may also be that we’ve been reminded of the importance of the slow. I’ve no doubt my grandfather would have heartily approved.