BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Iris Spark

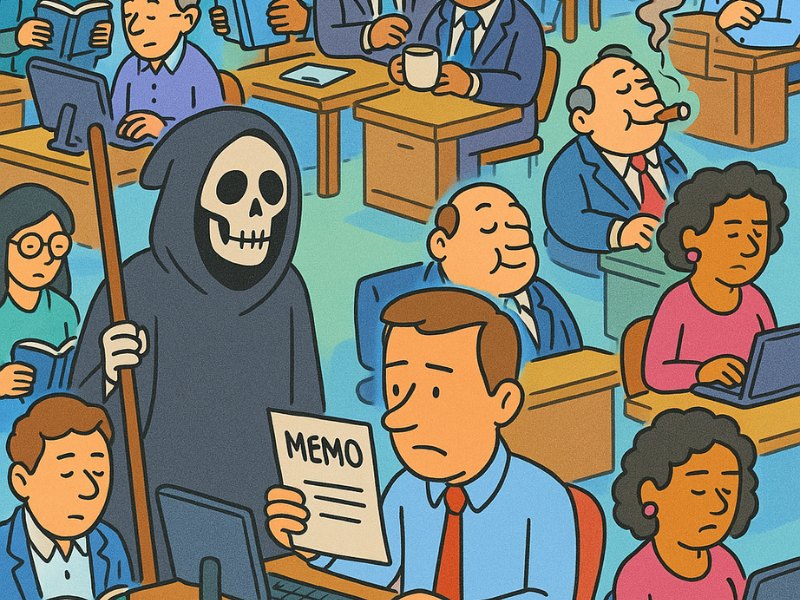

There is a moment in every great crisis where someone, somewhere, knew the problem was coming. But their concerns were ignored, dismissed, or buried under the weight of bureaucracy. We’re not really in a position to say this sort of thing is entirely to do with other people: we all in our lives have things flash across our desks – or even across our minds – and we think: “Might that be significant?” “Should I do something about that?” But there might be a million reasons not to: we’re tired, or there is something else pressing down on our attention, or perhaps we tell ourselves it’s not really our responsibility. Someone else will handle it. It’s only later that we realise we ought to have done something.

These things in our daily lives might be trivial enough: forgetting to renew a parking permit with the angels at Southwark Council; replying to an email; planning ahead for a birthday party.

But the problem is that this exact habit when it replicates during a senior decision-making role can be catastrophic. And we’re seeing that pattern repeat again and again. It happened with the Post Office scandal, where sub-postmasters were falsely accused of fraud due to a flawed IT system. It happened with Grenfell, where residents warned of fire risks long before tragedy struck. It happened in the Church, where allegations of abuse were overlooked to protect reputations. In each case the same pattern is at work.

It happens, repeatedly, because of one fundamental flaw in leadership: a lack of curiosity.

The Psychology of Power and Incuriosity

Dr. Paul Hokemeyer, a leading clinical psychologist, explains why those in power often fail to ask the right questions. “People in positions of power tend not to be particularly curious because they have no reason to be,” he says. “They are either getting what they want or myopically focused on getting what they want. Both situations diminish the leader’s motivation to stretch beyond what is in their immediate sight line.”

In other words, when things are going well—at least for those at the top—why shake things up? Why listen to the low-ranking employee waving a red flag when it’s easier to dismiss them as a pessimist?

But this isn’t just about laziness; it’s about psychology. Hokemeyer warns that “curiosity requires humility. Unfortunately, in today’s ethos of authoritarian regimes, humility has been replaced with hubris. And as we know from the Greek tale of Icarus, hubris breeds destruction.”

It’s a damning assessment, but history backs him up. Theresa May, in her book The Abuse of Power: Confronting Injustice in Public Life, reflects on how those in charge repeatedly fail to engage with difficult truths: “The powerful reassure themselves that nothing is wrong—until the weight of evidence is too overwhelming to ignore.” By then, of course, it’s too late.

The Importance of Curiosity in Leadership

Nicky Morgan, former Education Secretary, believes curiosity isn’t just important—it’s fundamental to good leadership. “There have been a lot of instances in the UK recently where the world would have been a lot better if the people at the top had been more curious about the problems beneath them,” she says.

Her list is long. “We’ve had the Post Office scandal, scandal in the Church, as well as Grenfell and a myriad of others.” In each case, disaster could have been mitigated, if not prevented, if those in charge had simply asked more questions.

But curiosity doesn’t just happen. Leaders need to build cultures where truth can rise to the surface. According to Hokemeyer, “The best way to maximize the flow of information from low to high is in a culture of psychological safety. The construct was developed by Amy Edmondson at Harvard Business School and refers to a culture where people can come forward with their mistakes, uncertainty, and doubts and be supported rather than judged.”

Edmondson first introduced the idea of psychological safety in the late 1990s while researching how medical teams function. She discovered that the highest-performing teams weren’t necessarily making fewer mistakes—they were simply more willing to admit them and learn from them. As she explains, “Psychological safety is not about being nice. It’s about giving candid feedback, openly admitting mistakes, and learning from each other.” In her book The Fearless Organization, she warns that in cultures where fear dominates, there’s a tendency for employees to stay silent, and for vital issues go unaddressed: “Silence is the enemy of high performance. If you don’t have psychological safety, people are afraid to speak up, and when that happens, organizations fail.”

This means no more punishing the whistleblowers. No more fostering an environment where bad news is something to be buried. Because, as Morgan points out, “The most vital information has to land on the desk of the ultimate decision-maker.” If it doesn’t, what’s the point of leadership at all?

A Failure to Listen

Look at what happened at Grenfell. In 2016, resident Edward Daffarn wrote in his community blog: “Only a catastrophic event will expose the ineptitude and incompetence of our landlord.” One year later, the tower burned. As Theresa May later reflected in Abuse of Power, “Grenfell was not just a tragedy; it was a national shame. Time and again, warnings were ignored. Those in charge simply did not listen to the people they were supposed to protect.”

Look at the Post Office scandal. When sub-postmasters complained that the Horizon IT system was faulty, they were dismissed. Alan Bates, who led the legal fight to expose the scandal, recalls how impossible it was to be heard: “You were either lying, incompetent, or on the take.” The independent inquiry into the scandal later found that the Post Office had “repeatedly and deliberately” ignored evidence of faults, prioritizing its own reputation over the lives it was destroying. It took over two decades before justice was even acknowledged.

And look at the Church of England, where the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, resigned after admitting that survivors of abuse had been failed. The Church’s safeguarding failures weren’t new. Reports had been coming in for years, but, in Welby’s words, “we simply didn’t listen.” The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA) was damning: “The Church’s culture of secrecy and deference allowed abusers to hide in plain sight.”

These aren’t just missteps; they are systemic failures rooted in a refusal to be curious about the uncomfortable. When W.H.Auden wrote that ‘the crack in the tea cup opens a lane to the land of the dead’, he was observing that sometimes the greatest catastrophes stem from small things.

The Opportunity for Change

So what is to be done?

Firstly, organizations need to build psychological safety. “This, like all organizational cultures, needs to start at the top,” says Hokemeyer. “The C-suite executives must cultivate humility, strength, curiosity, wisdom, patience, and drive.” That’s a tall order, but necessary. Without it, businesses, governments, and institutions will continue to repeat the same failures – and we’ve seen enough of what that looks like.

Secondly, curiosity needs to be embedded in education. “We need to be teaching young people not just to learn facts, but to question them,” says Morgan. She believes that fostering curiosity early is the best way to create a generation of leaders who don’t accept things at face value. “It’s not enough to say ‘this is the way things are.’ We need to encourage young people to ask ‘why?’ and ‘what if?’”

Thirdly, we need to abandon the mistaken belief that workplace culture should be “nice.” As Edmondson points out, true psychological safety is not about avoiding discomfort but about making space for honesty. “Psychological safety is not being nice. It’s about candour, about making it possible for people to speak up,” she argues.

The problem is that many workplaces conflate niceness with people-pleasing, which, in reality, leads to avoidance and stagnation. As psychologist Dr. Harriet Lerner explains, “Niceness is overrated. When we prioritize being nice over being honest, we end up betraying ourselves and enabling dysfunction.” Dr. Jordan Peterson echoes this sentiment, warning that people-pleasing is often “a deceptive strategy” to avoid conflict while allowing issues to fester unchecked. If organizations want to solve real problems, they must replace superficial harmony with a culture where respectful challenge and tough conversations are the norm.

Finally, we need to reward those who speak up. Right now, the systems we operate in tend to punish dissenters, not elevate them. That has to change. The biggest disasters of the past few decades weren’t surprises to everyone—someone always saw them coming. The challenge is making sure they are heard before it’s too late.

Because incuriosity doesn’t just lead to stagnation. It destroys careers, damages institutions, and—when taken to its worst conclusion—costs lives.