BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson asks what we can learn from the great general in our working lives

There is a famous line by the 20th century Chinese statesman Zhou Enlai. When asked what he thought of the French revolution, he replied: “Too soon to say.” The same might be said about Napoleon: we’re too near him to know for sure what he means to us.

That doesn’t stop us trying to find out. The recent release of Ridley Scott’s film Napoleon (2023) has proven beyond doubt that Napoleon remains both compelling and controversial – as lively in his importance as many a living figure. By discussing Napoleon, we somehow give an account of ourselves.

Scott’s film establishes itself as a must-watch just by virtue of its title. It isn’t quite the film we want or need, but it is better to have it than not. All Stanley Kubrick fans lament the fact that the great director never finished his own version – and there is much hope surrounding the news that Steven Spielberg is now filming a seven-part series for HBO based on Kubrick’s script. For now, we can make do with this: Joaquin Phoenix as a gruff Napoleon, less intelligent by many magnitudes than the actual Napoleon; brilliantly shot battle scenes; and a film that feels oddly both too short and too long at the same time. What’s good about it will make us want to know more about Napoleon; what’s not so good will ensure that our appetite for stories about Bonaparte will not allay.

After Scott’s film was initially screened, and the reaction came in, one came to realise that however porous the world’s nations have become, they still mean something to most people. That’s because in France, the film has been considered anti-French, a viewpoint which has been much less notable in the English and American coverage. It was as if the Napoleonic Wars had never been away, which in itself brings to mind another quote, this time by the American novelist William Faulkner: “The past isn’t dead. It isn’t even past.”

This quote, whose truth has grown on me over the years, is undeniably the case with Bonaparte. Napoleon, perhaps more than any other historical figure, retains the power to affect us in the here and now, though he has now been dead for over two centuries.

What is it that makes him so powerful and even attractive? His daring, his military competence, and his glamour tend to spark the imagination of successive ages. Nobody is really immune from his dash, his competence, and the outsized nature of his deeds. Readers of Andrew Roberts’ Napoleon the Great will find it striking how much Napoleon wrote, especially in his youth – stories, plays, essays, all of them very bad. But really Bonaparte is the archetypal man of action and our interest in him perhaps speaks to a deficit in us: compared to Napoleon almost everyone else in history is too sedentary. To look on him is to marvel at a different energy altogether, one we can learn from.

But there’s a paradox at work here. Napoleon’s very power to interest us may make us wonder a bit about the validity of the helter-skelter progress we sometimes think we are making. Why, if we’re so content to rush off into a future of general artificial intelligence and drone cars and so forth are we so easily arrested by this man who lived not only before the Internet and air travel, but who lived most of his life without the steam engine having been invented?

One possible answer is that Napoleon, as Scott’s film shows well, remains a fascinating instance of human potential made actual. By any measure, he did amazing things – even though we might not agree with much of what he did. He stalked continents; proved himself one of the best military commanders in history; and created a legal system, the Napoleon Code, which is still in force in some 120 countries. It was the historian Kenneth Clark who said that Napoleon, for all his faults, was a difficult person entirely to discount. “We can’t quite resist the exhilaration of Napoleon’s glory,’ as he said in his landmark TV series Civilisation.

Glory, it must be said, has had a hard time of it in the past two centuries – not least because Napoleon, its principal embodiment, was defeated in the end. The poetry of Wilfred Owen (1893-1918) contains the best descriptions of why glory is at the very least to be distrusted. Put simply, it leads to needless death – Owen’s among them. So Napoleon embodies a discredited notion, but still we find ourselves affected by him.

I think some clue can be found in the etymology of the word ‘glory’ which comes from the Old French ‘gloire’: “the splendor of God or Christ; praise offered to God, worship”, though it also has connotations with the Latin word ‘gloria’ which naturally has pre-Christian associations of ‘fame, renown, great praise, or honour”. This might make us realise that Napoleon, in so embodying glory, is a sort of ladder we might descend into the deep past – almost into another version of human achievement, full of a kind of blazing intensity and adventure.

There is evidence that Napoleon knew that he might serve as a powerful, almost Pharaoh-like, symbol for his contemporaries. Take, for, instance, Ingres’ superb portrait which summons to mind Charlemagne: here we see the paraphernalia of immutable power. Napoleon, too fleetingly, understood himself as a force for stability – and, of course, in relation to what had gone before in the shape of the anarchy of the revolution, that wasn’t necessarily difficult.

But he was too complex to be only that – he was also on the move, athirst, full of a certain wild rampancy. He could never be a figure of unity and a figure of conquest at the same time. In his essence he was too questioning for that. This tendency to ask quick volleys of questions was the backbone of his character. Here is Roberts describing an encounter with the prostitute to whom he probably lost his virginity in Paris when a young man:

“He asked her where she was from (Nantes), how she lost her virginity (‘an officer ruined me’), whether she was sorry for it (‘Yes, very’), who she’d got to Paris, and finally, after a further barrage of questions, whether she would go back with him to her rooms…”

And here he is towards the end of his life, as witnessed by William Warden on the Northumblerand in transit to his final ending up in St Helena:

“His conversation, at all times, consisted of questions, which never fail to be put in such a way as to prohibit the return of them. To answer one question by another, which frequently happens in common discourse, was not admissible with him. I can conceive that he was habituated to this kind of colloquy…’

He certainly was habituated to it – it was a lifelong trait, which it would have been good if Scott’s film could have better conveyed. Napoleon’s curiosity was insatiable: given command when very young of the French army in Italy, he threw himself into the history of campaigns there.

But his curiosity also had its limitations. If we ask to what end he was asking questions then the answer is conquest. This was his raison d’être – and territorial conquest is always bound up in space and time, and so can never quite be enough. Perhaps it is never especially sane. Restlessness was the chief characteristic of his time – usually a restlessness combined with a nodding understanding of the centredness of the classical world. This paradox can be seen in figures as various as Byron, Beethoven, and Goethe. Goethe worshipped Palladio but wrote The Sorrows of Young Werther.

Napoleon til Hest fra bogen Kunstnere Z: David, Jacques-Louis 2005

Fotograf:.

ACC:.

HD Afdeling. Det Kongelige Biblotek.

The boon of this romantic restlessness was that it was exciting; the problem was that nobody particularly knew what they were travelling towards, a characteristic we often seem to have inherited in our own hyperactive inattention. One of Napoleon’s greatest contemporaries William Wilberforce, in his passion to abolish slavery, had a far clearer understanding of what life is than any of those others. This is one of the reasons why, in the end, Britain won the Napoleonic Wars: it was more securely anchored in a sense of identity than revolutionary and Napoleonic France. Napoleon was a far better military leader than any alive – in fact, he was the best military commander of all time. But his brilliant victories were always in service to nebulous aims.

This heady Napoleon – the one who, unlike Ingres’ version, actually existed – can be seen in David’s Napoleon Crossing the Alps: it is a picture full of movement, of appetite for the next thing. It is this need of motion – the lack of a viable centre – which really came to define him, and which brought about his own destruction. Some of the more picturesque scenes in Scott’s movie show the magnitude of Napoleon’s error in marching on Russia in winter.

This then is Napoleon: a new kind of hero, but someone also redolent of the old Christian Kings, and the pre-Christian Emperors. Of course, Napoleon himself isn’t someone we would think of as Christian in any meaningful sense – the body count alone arising out of his campaigns might make us laugh at such a notion. But in our disconnected and inchoate world, there will always be those who look to the strongman for solace, even a dead one. They are markers of what might be possible when we are feeling downtrodden and small. The spread of digitalised democracy hasn’t decreased this hunger; it has augmented it, as the existence of figures as various as Donald Trump and Viktor Orban, Vladimir Putin and Narendra Modi shows. Most of the people alive today who support these people, would have been sure to have supported Napoleon in his own day. The dynamic towards authoritarianism is a recurring one, and it is partly because it must always be fought that we can’t always be sure at any one time about the precise state of Napoleon’s legacy.

Yet our strongmen are neither so clever nor so interesting as Napoleon. Our politics seems full of a sort of pantomime glory which is sometimes called Punch and Judy politics. It is tempting to argue that without Napoleonic conquest the stakes simply aren’t high enough to make genuinely gigantic political figures.

Certainly the idea of glory seems to reach its apotheosis somehow with the conclusion of the Napoleonic wars. A sort of grey filter appears to descend which has to do with the nature of the victors – the dowdy Victorians – and with the absence of Napoleon himself. The wars which occurred during the 19th century lacked the drama of Napoleon’s wars. We don’t really watch films about the Crimean War. In fact, the principal development in war in the 19th century after Napoleon’s death is probably the writing of Tolstoy’s War and Peace, in which the romantic view of Napoleon is admitted into a vast canvas which is also at pains to show the grim reality of war. Tolstoy anticipated the War Poets by around half a century.

Clearly, the Tolstoyan view of war was important and much was gained: a healthy loathing of carnage. Human beings felt able in the wake of Napoleon to think about the individual life which is sacrificed by the Bonapartist need of conquest. We began to loathe, quite rightly, what war actually is. Owen called the idea that it’s sweet to die for your country the old Lie – and every Remembrance Day we come together in full agreement. One of the leitmotifs of my own life has been to visit the sites of atrocities. I have seen Hiroshima, Auschwitz, Anne Frank’s House in Amsterdam, Kilmainham Jail and Robben Island. They all tell the same story of the collateral damage which governments inflict on people when they hope nobody is watching. In one sense, Napoleon is on the side of the governments not the people.

Yet watching Scott’s film, it doesn’t feel quite so simple as that. He was also in another sense of the people, in that he was charged with bringing to some kind of order the unruly energies of the revolution. Napoleon’s Hundred Days would not have occurred without his having secured some powerful connection with the people. The complexity of Napoleon is that he emerged out of a set of forces which we have to some extent accepted. Furthermore, there was always a degree of treachery in Britain about Napoleon. Charles James Fox – essentially the Leader of the Opposition during the lengthy administration of William Pitt the Younger – had three meetings with Napoleon, and lavished Bonaparte with praise, saying that he had “surpassed…Alexander & Caesar, not to mention the great advantage he has over them in the Cause he fights in.” We would be surprised to hear Starmer say something like this about Vladimir Putin – but perhaps it is a measure of Napoleon’s attractiveness that he had supporters even in the House of Commons.

Yet it was also Kenneth Clark who approvingly quoted John Ruskin’s observation: “All the pure and noble arts of peace are founded on war; no great art ever yet rose on earth, but among a nation of soldiers.” Predominantly because of the horrors of the 20th century, and in our era of declining defence budgets, we find it hard to understand how much our forebears accepted soldiery as a pursuit. Much of the admiration towards Napoleon was therefore aimed at his military ability.

It can be possible to admire a thing done well for its show of technical and leadership ability – and few people have done anything as well as Napoleon made war. His strengths included a rapport with his troops, an ability to think tactically around the terrain of a situation, and an ability to ruthlessly seize the opportune moment. It might be added that these traits would be just as useful in the boardroom as on the battlefield: everyone who aspires to leadership will therefore have something to learn from Napoleon. This is categorically not true of Hitler, who people, possibly including Scott, sometimes want to adduce as a comparison to Napoleon.

Where I think Napoleon is deficient is in his sense of himself, and in his worldview. Heroes forget they are human at their peril. Bonaparte once said that if he were to fall off a building, he wouldn’t be scared but would take a last calm look around. This is unlikely – he would be as scared as the rest of us. In forgetting his humanity, he was unable to accept that humanity is wedded in some way to fear since we are in a universe we don’t understand. As a result he miscalculated about the wishes of others, what they would and wouldn’t do: most notably, the whole world was unlikely to want to live under his regime. Other considerations, which he didn’t understand, were in play. This is because his worldview was essentially Voltairean, and I don’t think it occurred to him in the insane rush of his life that the Voltairean view of life might be limited, or wrong, or both. In this he was very much a man of his time, and not, as he wished to be some eternal Caesar who straddles all the ages. The Voltairean view has nowhere to go, since it refuses mystery.

Nevertheless, some of the best scenes in Scott’s movie bring the 19th century battlefield to life: we witness the sheer flurry and insanity of battle, as well as Napoleon’s ability to exist within a complex situation and calmly read it. When asked who was the best general in history, the Duke of Wellington (conveyed here in a hammy performance by Rupert Everett) replied: “In this age, in past ages, in any age, Napoleon.”

Ruskin’s quote about the connection between military ability and literary output is open to the objection that we wouldn’t necessarily call Napoleon’s reign a brilliant time for literature. In fact, his biggest contribution to literature was again probably War and Peace, in which book he appears and which is impossible to imagine having been written without his extraordinary life. It took a writer of the magnitude of Tolstoy to approach Bonaparte.

But Ruskin’s idea cannot nonetheless be easily dismissed. It might be that soldiery and the skill that surrounds it are what’s missing from our society – that we have become too inward, bloated and self-regarding in a time of peace to produce work that is sufficiently vibrant and true to feel great.

In time, the example of Napoleon faded and the only clear historical example of le gloire since his life, is contained in the life of his admirer Sir Winston Churchill, who also depended on a war – albeit one he didn’t start – as the crucible in which to forge his own reputation. The peace of 1945 has broadly lasted until the present day, and it remains the case that wherever we see war we despise it, as in Ukraine or in the Holy Land.

This makes it all the harder to say that something was lost with the demise of Napoleon. But if something was indeed lost then that something was ambition. Most of us today, as we leave university, seek to join society and joining is an inherently unglorious thing to do. To coopt oneself can be to dream small. In his book Bullshit Jobs, the late philosopher David Graeber issued a brilliant takedown of the contemporary economy, which can sometimes seem to specialise in creating roles whose mundanity might be deemed the polar opposite of the glorious. There is something almost preternaturally un-Napoleonic after all about a middle manager.

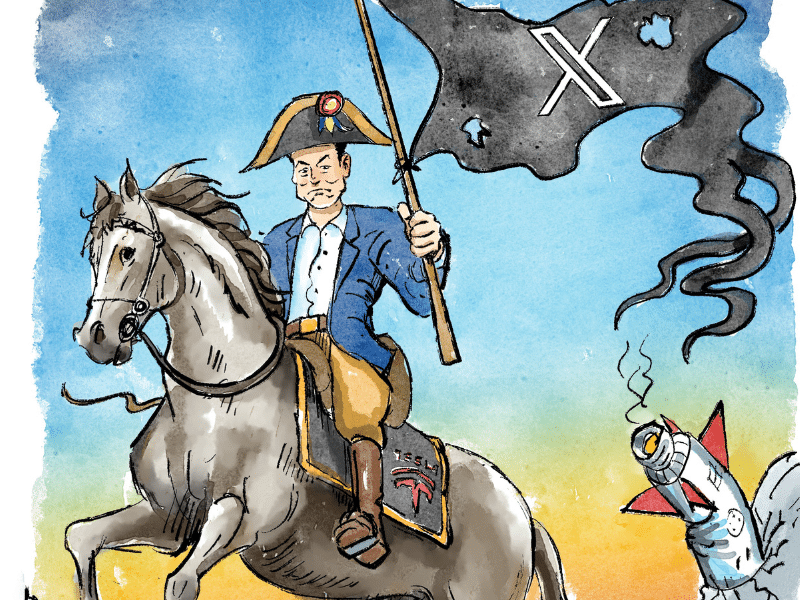

This is not to say that the Napoleonic spirit is entirely absent in our world. In many ways, his example can most be found in today’s tech giants, especially in the companies of Elon Musk. Musk himself, when we see him at SpaceX or Tesla, in his constant questioning, his invention, and his desire to push frontiers, bears a remarkable resemblance to Napoleon in a battlefield situation.

Did Napoleon’s defeat lead to the banality of the modern world? No, we created that – and in fact, there’s a good case that Napoleon’s ultimate influence is now more to be found in the realm of the imagination than in political reality. Napoleon left remarkably little political legacy. Gore Vidal mischievously jokes in his novel Burr that Thomas Jefferson had a far bigger impact on history than Napoleon: the American revolution actually lasted and is still admired today, though it is also in peril.

Napoleon in fact never could have united Europe, especially without being able to control the seas. George III and his brilliant Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger were not about to agree to it, and he was probably temperamentally ill-suited to the creation of anything lasting. Napoleon’s bout of conquests came in the wake of the French revolution and since we to some extent inhabit the aftermath of those times, we can hardly access now the note of dismay across Europe at the idea of the old medieval order being so absolutely swept away.

Very occasionally, we glimpse what we were fighting for in opposing Napoleon. Napoleon’s greatest contemporaries have all had a subtle but real influence – in fact their comparative gentleness is liable to make us underestimate them. Arguably, the greatest of them was William Pitt the Younger, whose quiet conservatism and remarkable financial competence have had their own legacy. Pitt, like most of his contemporaries, believed in the monarchy, and although the monarchy has been watered down to a considerable extent, we saw in the coronation of Charles III last year how it has continued – and how its symbolism is even in many respects unchanged. Conservatism has had its victories too; we live in the time of Charles III as much as in the era of Rishi Sunak.

Similarly, we can see how the Founding Fathers of the United States, also Napoleon’s contemporaries, remain in the collective consciousness in a more meaningful way. Napoleon is a kind of a blaze, but he never, as Jefferson did, defined a philosophy. Life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness may in some way be a limited goal for a government to espouse – but it has been remarkably durable. Similarly, the financial system created by Alexander Hamilton has endured – and there is now a musical to show for it.

This isn’t to say that Napoleon is without concrete political achievements: in education with the creation of the University of France, and of course in law, he had remarkable impact. His love of books is an appealing thing about him, as is his occasional generosity when in power to those who had helped him on the way up. But Napoleon remains a riddle – since he opens up with startling immediacy onto the riddle of ourselves. If we ask what we really think of him, I suspect Enlai was right. It’s too soon to say.