BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson

I. At Claridge’s

Dame Judi Dench doesn’t walk; she glides. Even at 90, she seems to move as though through some different element — air, yes, but mixed with light. There’s an effortlessness to her presence, a practiced grace that doesn’t just enter a room; it reshapes it. I see a group of girls have their photo taken with her, and she moves away they jump up and down in delight like they’ve just finished their final exams: “She’s so lovely!”

The scene is Claridge’s and her 90th birthday – well, not exactly, since her real birthday was las year and it is now May 2025, as close to her 91st birthday as that other milestone. In fact, it’s a fund-raiser organised by the photographer and protégé of Henry Moore Gemma Levine to help raise funds and awareness for lymphoedema research. This is a disease that rarely receives the attention it deserves, despite its often devastating effects. Since her own diagnosis, Levine has thrown herself into the cause with both urgency and grace, and this event was another example of how she leverages art for activism.

As part of her training, Dench was taught what is known as the Alexander Technique, and I notice how a fluency of movement characterises her, and how a spatial awareness is still there even in someone now very near total blindness.

All of the famous have their power. In my own life, I remember the gallery of the well-known: the jauntiness of Roger Daltrey; the quiet bafflement of Andre Agassi at all the fanfare; Sting’s seigneurial good cheer; and the

And it’s never anything less than very bizarre.

Often I’ve seen a well-known person arrive at an event and, almost involuntarily, you flinch slightly. There’s a ritual in that moment, one which both parties know by heart: the person is recognised; the observer performs recognition. And in the eye of the storm, the famous person — that weary dancer in a dance they never quite chose — steels themselves once more.

It is sometimes possible to see her there up on the stage and think that there must be many better things in the world than to be globally famous and admired. It’s possible to study Shakespeare all your life, to devote every fibre of yourself to the transmission of language, memory, and meaning, and to find yourself paraded in public like some curious relic — an artefact of culture in a time that increasingly undervalues it.

Despite this, grace can go a long way, and as I talk to Dench while she’s being sculpted I notice that she has a considerable amount of that. I am aware too that she must be under a certain amount of stress, not being able to see, and sensing people, coming in and out of her orbit, but not knowing who they might be. Even for someone used to being looked at, this must be difficult. Even so, there is no hint of diminishment.

For a while I must admit I’m one of those looking at her and this gives me a moment to look at the famous face, and then look at the sculpted likeness by Frances Segelman. “I can imagine what Dame Maggi Smith would say if she were alive today. How wonderful to see Judi being turned to a monument before our eyes.”

Segelman works swiftly and clearly enjoys her work. What one thinks as one watches is not just of this face: the kindly eyes, the look of earned wisdom and the quiet dignity – but of all the characters it’s also inhabited.

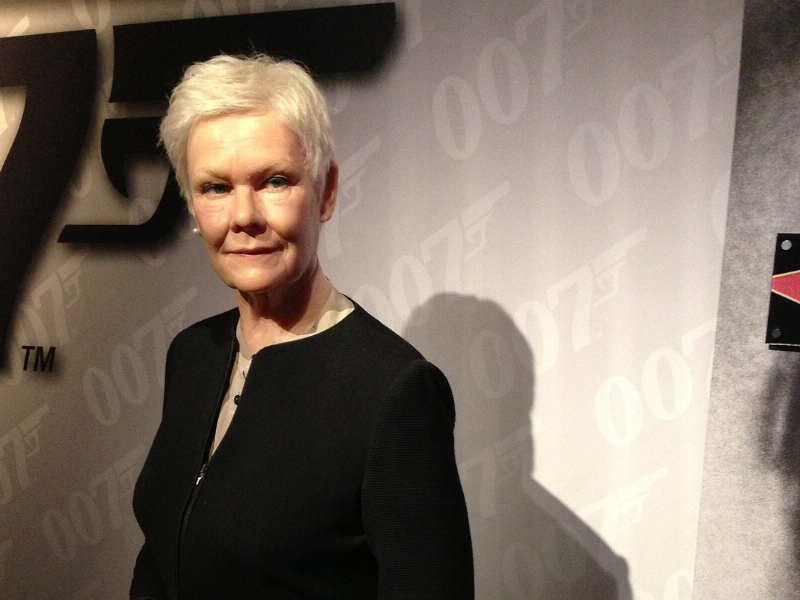

This is the face that has been Queen Victoria in Mrs Brown and again in Victoria & Abdul, where warmth and steel lived side by side. It’s the face that was both commanding and broken as Iris Murdoch in Iris, and that brought a quiet, terrifying gravitas to M in the James Bond franchise. On stage, it’s been Ophelia, Cleopatra, Lady Macbeth – each one rendered unforgettable with that unmistakable blend of clarity, humanity, and force.

Across film, theatre, and television, Dench has worn the masks of monarchs, matriarchs, mentors, and mischief-makers – from the imperious Queen Elizabeth I in Shakespeare in Love to the humorous and warm-hearted Jean in As Time Goes By. The face Segelman sculpts is not just Judi Dench’s; it is layered with the memories of all the lives she has brought to life – a composite of performance, power, and presence.

She has moved audiences in quieter, more intimate roles too – as the devoted Philomena Lee searching for a lost son, or the steadfast Mrs. Fairfax in Jane Eyre. Each portrayal feels deeply lived-in, shaped by empathy and an acute understanding of human complexity. Even in smaller parts, she lends depth and nuance that make scenes linger in memory.

What Segelman captures is not just a likeness, but a legacy – the embodiment of a performer who has shaped the emotional landscape of British acting for more than six decades. Dench’s face, rendered in clay, holds more than expression: it holds stories, centuries, and an enduring commitment to truth in performance.

As the speeches went on, Dench, ever the professional, dissolved the reverence with a deft quip: “I hope you’ve got my good side,” she said to the sculptor, with perfect comic precision. The room exhaled.

II. The Spell of Beginnings: York, Shakespeare, and Siblings

To understand Judi Dench, one must return not just to the geography of her beginnings, but to the atmosphere. Born in 1934 in Heworth, a suburb of York, Judith Olivia Dench grew up in a house where the arts were not some lofty ideal but part of the nature of daily life. Her father, Reginald, was a GP and medical officer for York Theatre Royal; her mother, Eleanora, a devout Irish Catholic who valued education and civility. In respect of the latter, we can imagine that Dench may have drawn on her in her most recent great role in Sir Kenneth Branagh’s Belfast. It was at this intersection of science, discipline, faith and theatre that Judi Dench was formed.

She was the youngest of three children. Her elder brother Jeffery Dench would go on to become a respected Shakespearean actor himself, and it was in watching him perform that young Judi had her first brush with destiny. She has spoken often of the moment she saw her brother playing in Macbeth at St. Peter’s School, York. The line — “What bloody man is that?” — shocked and enthralled her. “Shakespeare was swearing!” she recalled, wide-eyed, even in later retellings. She was seven or eight, and she was hooked.

From those early years, she was marked not by arrogance, but by an intense, almost sacred curiosity. One of her childhood friends later recalled that Judi “seemed older than the rest of us, even when she was little. There was something in the eyes.” Those eyes, which convey so extraordinarily everything from Iris Murdoch’s bafflement at her own declining powers to Lady Macbeth’s hunger for power, have been an essential part of her art ever since.

Dench’s path to the stage wasn’t linear. Her first ambition was to become a set designer. It was only when she attended the Central School of Speech and Drama in London — then housed at the Royal Albert Hall — that she began to move from behind the scenes to centre stage. Her time at drama school has become semi-mythical. In her first audition, the examiner famously told her she would never work in film due to her “funny face.”

And yet that face — now iconic — has gone on to inhabit queens, spies, lovers, mystics, and mothers with an emotional clarity that has moved generations. It’s a useful reminder not to listen to people who say you can’t do something – the truth is that many people have secret potential within them, and that this simply needs to be allied to the will, as it was in the case of Dench.

At Central, she trained under luminaries like Yat Malmgren and was part of a golden generation that included Vanessa Redgrave and Ian McKellen; the latter would decades later play Macbeth to Dench’s Lady Macbeth in seminal roles for them both. One of her teachers, who later directed her, remarked that Judi “listened harder than anyone I ever taught. She was completely present.” It is a reminder that commitment to a task

After graduation, she joined the Old Vic Company and made her stage debut as Ophelia in Hamlet in 1957. To this role, she brought a startling freshness and emotional directness to the role of Ophelia. Though it was her professional debut, Dench was already marked by an instinctive clarity of speech and a remarkable emotional intelligence. Her Ophelia was not a fragile, ornamental figure, but a young woman whose descent into madness felt palpably real — driven not by hysteria, but by heartbreak and confusion in a collapsing moral world.

Dench avoided sentimentality, instead grounding Ophelia in a youthful sincerity that made her unraveling all the more painful to witness. Audiences and critics noted her expressive face and voice — tools she would later wield with great power — already carrying the seeds of the control and grace that would define her career. In a role often reduced to tragic passivity, Dench offered something more searching: the quiet fury of a woman undone not by weakness, but by betrayal.

From there, she joined the Royal Shakespeare Company, where she would become a cornerstone. But it wasn’t all triumph. Early reviews were sometimes tepid. A Times critic once dismissed her Cleopatra as “too small, too northern, too polite.”

And yet, she remained grounded. One former stage manager described her as “the most generous person in the green room.”

What we begin to see here is a career not built on celebrity, but on trust: trust from colleagues, trust in the work, and ultimately, trust from the audience. That trust has never been broken.

III. Apprenticeships in Genius: Mentorship and Magic

There is a moment in every great artist’s life when imitation gives way to innovation — when homage transforms into authorship. For Judi Dench, that transition didn’t come with fanfare or flashing lights, but like a candle taking to flame: quiet, resolute, irreversible.

It began at the Royal Shakespeare Company — that fabled, ruthless crucible — where Dench, still in her twenties, found herself among titans. She didn’t blink. Instead, she watched. Paul Scofield, with his extraordinary presence best gauged today in A Man For All Seasons; the legendary Peggy Ashcroft; Ian Holm, flickering with intensity. She was learning not in classrooms but in the theatre itself — from how they entered a scene, how they paused, how they said nothing. Greatness was not a performance, she realised. It was an accumulation of attentiveness. It is out of the crucible of this experience that Dench’s particular kind of watchful acting was born: by paying attention herself, she discovered over time that her acting could have exactly the intelligence of someone learning about the world. All her performances show people unusually alert to the world, and this is why we watch her so minutely – because it tracks our sense of how life might be if we were similarly switched on.

One day, she was rehearsing The Merchant of Venice and faltering. John Gielgud, never one to dispense compliments lightly, murmured from the darkness: “Don’t push. The words will carry you.” That phrase — deceptively simple — became something like a mantra. She understood that the actor’s job wasn’t to impress but to channel. Not to dominate a text, but to be possessed by it.

I ask Dench what Shakespeare would have been like to meet, and she says, unconsciously echoing Schofield’s most famous film role: “A Man for all Seasons.”

Would he have been the quietest person in the room? “Perhaps,” she says, “but certainly the most intelligent.”

The anecdotes from this time are instructive. Peter Hall once stopped a rehearsal and, after a long silence, simply said, “Judi, you’re not acting the emotion — you’re being it. Carry on.” And so she did. With quiet ferocity and humble genius.

Simon Callow — her later friend and sometime co-star — first encountered her as a member of the audience. He was watching television, the four-part John Hopkins masterpiece Talking to a Stranger. “She was on fire,” he said. “The camera didn’t just love her — it obeyed her.” The performance was a psychological scalpel: Dench playing a daughter navigating the wreckage of family, each episode rotating the point of view like a lens turned to focus. Even then, she had that extraordinary control — to let the emotion tremble just behind the line, waiting, coiled.

From the outset, she rejected the glitz. After curtain calls and critical raves, she would retreat. Make tea. Call her mum. “You mustn’t believe them when they say you’re brilliant,” she once said. “Because then you might have to believe them when they say you’re not.”

There’s something profound in that: a refusal to be made a monument while still breathing. A faith in work, not worship. And what astonishing work it was. There was Sally Bowles in Cabaret, a part so closely associated with Liza Minnelli that it might have been suicide to attempt it. But Dench was “the quintessence,” said Callow. Her Sally wasn’t all sparkle and sin — she was bruised, human, riveting. You saw a person, not a performance.

There was London Assurance, that half-forgotten gem from Dion Boucicault, dusted off and suddenly glimmering, thanks to Dench and Donald Sinden. Critics didn’t know what to do with it. The text was antiquated, fussy — and yet she made it sing. Pregnant with her daughter Finty during the run, she joked about being wildly miscast as a dewy Gloucestershire ingénue. But her comedic timing was surgical. She made every syllable land.

These weren’t just performances; they were demonstrations of a philosophy. Dench doesn’t perform to show off. She performs to serve the work — and perhaps, deeper still, to serve the truth. Her entire career has had that sense of being in quiet alignment with something larger. She carries lines like prayers. You get the feeling she’s never said a word on stage or screen she didn’t first feel vibrating in her bones.

The genius of Judi Dench lies in her restraint. She never shouts. She barely gestures. But she listens so completely that everyone around her becomes better. Like all great artists, she seems less interested in expressing herself than in making herself available to expression.

Her mentors taught her to aim for the real. They taught her to distrust applause. They showed her how to be timeless without ever seeking to be fashionable.

And so she became something rare in British theatre: an actress whose fame does not obscure her, but clarifies her. Whose presence on stage makes everything else more visible. Whose entire life is an argument for the kind of greatness that is only possible through attention, patience, and a nearly devotional humility.

IV. The Daughter, the Day, and the Dance of Grace

After the sculpting had finished and the crowd had begun to disperse into Claridge’s mirrored corridors, I found myself chatting with Finty Williams — Judi Dench’s daughter. Finty had just performed a poem onstage which she had written for her mother, and I was moved by it: I could sense that performing the poem had been hard and so asked if she wrote poems generally. “This is my only one,” she said and I expressed surprise and congratulated her on it.

It was a soft moment after the spectacle, and something about Finty’s openness made it clear: she has grown used to living next to greatness — and though it has likely not been an easy life, she has handled it well, and is now an important support to her mother. I notice when she takes me over to Dame Judi, that she whispers in her ear: “Don’t worry, it’s only me” – meaning perhaps that the evening is indeed a little bit of an ordeal for her mother.

But before that moment, I learn a bit more about Finty, who is an actress in her own right. There is a trait I pick up on too and which I often find among the sons and daughters of the well-known – a kind of deliberate downplaying, designed to ground your life in something realer and more helpful than fame. She is the sort of person who seems to know — without ever needing to say so — that the world will never quite see her without comparing her to her mother. And yet she speaks of Judi not as a figure of public adoration, but as something deeper, something quieter: her mum.

Has it had its benefits? “She’s always been just there,” Finty said. “That sounds banal, but I mean it in the best way. Always listening. Always ready. The only time I ever used Mum’s fame is when I had a huge crush on Antonio Banderas and she managed to get me along to a film premier to meet him. I was so incredibly star-struck.”

Which tells you quite a lot about the absurdity of celebrity, as it’s not too difficult to imagine Banderas in turn being star-struck by Finty’s mother. Although he may not have been, one might say that given their respective acting abilities, he perhaps should have.

Finty has often offered a warmly candid glimpse of what it’s like living in the orbit of someone so globally known—both the perks and the little absurdities. She’s spoken about the moment their family went public with Tom & Geri, her mother’s beloved stage show, joking that fame became real when everyone at school started calling her “Dame Judi’s daughter.” From that moment on, everyday family life—shopping trips, casual meals—were seen through a new lens. Finty recalls her dear mum taking a deliberately normal role at home, one who adored cooking simple dinners and quietly retreating after a shoot. In these reflections, you see not the actress commanding stages and screen, but the mother coming off set, shedding roles and fame, and stepping gently back into familiar routines—always a little bit more tired but firmly grounded in the cocoon of family.

I then find myself saying that it’s a curious thing to talk to celebrities and say that it would be very interesting to ask Judi abut Shakespeare. Finty, cheerfully and kindly, says: “Well, let’s go and ask her.”

V. The Roles That Built the Myth: A Catalogue of Greatness

And so the career continued. It’s impossible here to survey the breadth and depth of the work. It is not that she has played many roles. It’s that she has redefined how those roles are meant to be played.

Let’s begin with Macbeth. Dench first performed Lady Macbeth for the RSC in 1976 opposite Ian McKellen. It is, by all accounts, one of the greatest performances ever given in the role. McKellen himself, not exactly prone to hyperbole, called her “demonic, carnal, and terrifying — like a woman possessed.” But what made it special was not its volume but its silence. Her Lady Macbeth did not scream for power — she whispered it into the ear of fate. And in doing so, she transformed the role from the shrill into the shrewd.

Then there was A Midsummer Night’s Dream, where she played Titania while heavily pregnant. “I looked like a Christmas tree,” she would later joke. But the effect was anything but comical. In her hands, Titania became a force of nature — not merely a fairy queen, but a matriarch of the cosmos, wielding her magic with earthy sensuality and unimpeachable command.

It is worth pausing to reflect on this: how many actresses could go from Lady Macbeth to Titania without breaking stride? And do so while working on tight budgets, in freezing rehearsal rooms, while raising a child, while staying human.

And then came the screen years — or, perhaps more accurately, the screen’s surrender to her.

Let’s talk about Iris (2001), where Dench played the older Iris Murdoch, while Kate Winslet portrayed her in youth. In that film, the descent into Alzheimer’s is rendered not as tragedy but as bewilderment. Dench didn’t act illness. She acted the slow disappearance of language. She made you feel the theft of memory. One of the final scenes, where Iris can no longer speak but smiles faintly at her husband, was described by The New Yorker as “an education in how to act without words.” You don’t watch Dench in Iris; you ache alongside her.

And then, of course, there was M.

When Dench was cast as M in GoldenEye (1995), the franchise had just endured the end of the Cold War and was looking for reinvention. What they got, when Dench entered, was revelation. In one scene, she refers to Bond as a “sexist, misogynist dinosaur,” and you could feel the tectonic plates of cinema shift. Here was authority not as masculinity, but as intellect. As stillness. As wit sharpened like a blade. She brought ballast to Bond, grounding the fantasy with something like actual stakes.

Pierce Brosnan was so intimidated he practically wilted on screen — and it worked. Judi was the real power in the room, and everyone knew it.

She would return again and again, reprising the role until her character’s death in Skyfall (2012), in a scene so touching it reduced audiences to stunned silence. No other character in Bond had ever been allowed a farewell like that. Because no one else had earned it.

Kenneth Branagh, who directed her in Belfast (2021), said recently: “You don’t direct Judi. You listen to her. You watch what she’s doing and then,

if you’re lucky, you get out of the way.”

In Belfast, she plays the grandmother — and in the hands of any other actor, that would’ve been a minor role. But with Dench, it becomes the emotional fulcrum of the film. Her eyes, framed in soft light, seem to contain all of Northern Ireland’s pain and resilience. You don’t realise until the final scene how much you’ve depended on her to keep the whole film afloat. And when she’s gone, the film dims slightly, like someone has turned down the wattage on the screen.

She’s often asked how she prepares. Her answer is always the same: “I don’t. I learn my lines, and I try to tell the truth.”

This is not false modesty. It is a reminder that acting, in her philosophy, is not about artifice but about access — access to feeling, to silence, to timing. There’s a scene in Notes on a Scandal (2006) where Dench’s character manipulates Cate Blanchett’s with the subtlest flick of an eyebrow. It’s not the words. It’s the breath between them.

Critics have tried, for decades, to name her magic. “Effortless,” they say. “Invisible technique.” “Stage presence.” But perhaps the best summation came from Ian McKellen: “She has a soul that listens. Most actors are trying to be heard. Judi is always hearing.”

And perhaps that is the secret. In a world of shouting, she listens. In an industry of surface, she gives us depth. She is not above us. She is among us — and yet, somehow, ahead of us.

Watching Judi Dench perform is to be reminded not only of what acting can be, but of what people can be, if they choose grace over ego, truth over display, and excellence over fame.

VI. Meeting the Monument

There is a temptation, with the elderly, to patronise — to use words like “sprightly” or “sharp as a tack,” as if mental clarity after 85 were an amusing party trick. But Dench obliterates that kind of thinking. She is — and there is no better word — present. Utterly, unnervingly so. You feel it in conversation: her gaze locks onto yours like a camera lens. You say something half-clever, and she quietly raises an eyebrow — not in judgement, but in a kind of mischievous encouragement.

When she speaks, it’s not about herself. It’s about the work. About the people she’s learned from, especially Shakespeare. “He was capable of being all things, “she says, “of imagining his way into every condition or attitude of life.”

What is it which makes the work so good? “It is all to do with intelligence. If a writer isn’t intelligent then they simply can’t surprise you – and they certainly can’t create work which endures like his does. I think what we’re seeing is somebody who is always in some way ahead of us. It’s this which accounts for the richness of the work.”

So the work is satisfying down the generations because intellect is always satisfying? “That’s right – it’s something that crosses the generations and is always exciting. That’s how it seems to me – it never seems to lose interest, only to gain it, the more you understand it.”

She is looking in my general direction, and I wonder what it’s like for her to be talking to me: am I shape? A strange suggestion of an interviewer? Or can she make me out a bit.

Not everything we say is serious. I say I heard that one of the soldiers in Macbeth ended up being eaten on the toilet by the T-Rex in Jurassic Park (1993). It’s not quite that she shrieks at that but she is obviously delighted: “Yes that was a surprise ending, wasn’t it?”

It is a nice image of how her own career has alternated between high art and the popular – how an actor today might be mastering iambic pentameter one minute, then eaten alive on by a dinosaur on a commode.

But as I speak with her, I notice the precision of her speech. It was said of the tennis great Roger Federer that he always seemed to have more time on the ball: Dench is a bit like this in interview, her answers seeming to come with a surprising immediacy and clarity. One suspects that this might be to do with the years spent caring — really caring — about each syllable of text. It’s the choice, again and again, to show up with all of yourself, whether you’re starring in a West End production or recording a radio play in a damp BBC basement.

I also get another sense. That kindness, in Dench’s world, isn’t decoration — it’s foundation. She has spent her life refusing the cynicism that so often creeps into fame. She doesn’t wield her celebrity like a sceptre. She wears it like the shawl she is wearing on the night I meet her — something to be shrugged off when it gets in the way.

As our conversation continued, Finty hovered protectively, as daughters do, not with panic, but with love that had clearly been deeply rehearsed across years.

VI. Grace Under Fire: The Psychology of Poise

There’s a moment just before the curtain rises — the hush, the breath, the eyes adjusting to shadow. It’s the moment when lesser actors panic, when the body betrays you with sweat, tremor, or forgetfulness. Judi Dench has admitted to this feeling. “I’m always frightened,” she has said. “Always.” But she shows up anyway.

What is that? Bravery? Grit? Madness? Or something rarer still — grace?

To understand Dench, one must understand not only her performances but the psychology beneath them. Dr. Paul Hokemeyer, the distinguished psychologist and author, has spent a career studying what he calls “grace under pressure” — and he places Judi Dench in that rare category of individuals who have mastered it.

“She speaks often about nerves before a performance,” Hokemeyer tells me. “And yet what she delivers is brilliance with warmth and control. That’s not contradiction. That’s grit — the ability to tolerate discomfort in pursuit of something meaningful.”

In this framing, Dench’s stage fright is not a flaw but a feature. It means she still cares. It means the work still matters. Hokemeyer explains that high-functioning people — whether actors, CEOs, or parents at the school gates — often experience intense emotion just before key moments. But what separates the truly exceptional is the ability to narrate those feelings without being controlled by them.

“She knows those nerves are part of the deal,” Hokemeyer says. “They give meaning to what she’s doing. And she knows that on the other side of that discomfort is something extraordinary.”

This is not just a professional skill. It is a life skill.

You see it in the way Dench handles interviews — gently correcting the questioner when they overstep, but never shaming them. You see it in the way she navigates fame — not with the hauteur of someone bored by attention, but with the amused patience of someone who knows it to be both ridiculous and, at times, useful. At one point, when I wish her Happy Birthday, she almost yelps: “But it was six months ago! This whole thing is just obscene!” But she is here, I can see, for her friend – and to do whatever she can to fight her friend’s disease.

Hokemeyer calls this ability “participant observation” — the capacity to be both in the experience and outside it, observing it. Judi, he says, has perfected this. “She can be in the moment emotionally, but also aware of how that moment fits into a larger story — the character’s, the audience’s, her own.”

It’s an emotional and intellectual feat. And it’s made possible by what Hokemeyer calls “a cultivated grace.”

“Grace is not just personality,” he says. “It can be learned. Judi Dench has it naturally, yes. But she’s also practiced it — with every line she’s delivered, every silence she’s held. She knows how to move through the world without causing harm. That’s the most elegant kind of power.”

In a world of overstimulation, where noise is often mistaken for significance, Dench reminds us that attention is a kind of gift. That composure is not about suppression but about alignment. That to be still is sometimes the most radical thing you can do.

Watching her, you get the sense that she’s not performing for applause. She’s not even performing for us. She’s performing for something older — perhaps even eternal. Call it craft. Call it vocation. Call it, simply, the work.

And when that work is done — when she steps away from the stage or the screen — she does not seek validation. She seeks tea. A dog to walk.

A friend to call.

This, too, is part of the psychology of grace. Knowing that the role is not the self. That the spotlight is not home. That the performance, however brilliant, is only one part of a larger life.

Hokemeyer leaves me with one final thought: “In moments of pressure, I sometimes ask my clients: What would Dame Judi do? The answer is usually to pause. To listen. To act with kindness and courage. And then — to go on.”

Go on. That’s the phrase that keeps echoing.

Go on, despite fear. Go on, despite grief. Go on, because you still have something to give.

It’s what she’s done, again and again. And it is, perhaps, the truest definition of grace there is.

VII. The Long Light: Opportunity, Legacy, and the Next Generation

What do you do when your role model is still better than everyone else?

It’s a question that young actors — and older ones too, if they’re honest — ask whenever Dame Judi Dench appears on screen. Her very presence is both galvanising and humbling: a reminder that mastery doesn’t always roar, and that longevity isn’t a fluke — it’s a form of character.

But Dench’s career also invites a more uncomfortable question: would a Judi Dench be allowed to become Judi Dench today?

Consider the landscape. Young actors today enter an industry more saturated and less forgiving. Image often trumps depth. Audiences scroll faster than they watch. Casting directors want followers, not apprenticeship. And yet — into that world, Judi Dench still stands as proof that another path is possible.

She didn’t come up through YouTube, she wasn’t “discovered” on a whim, and she certainly never danced for the algorithm. Instead, she trained. She waited. She failed. She learned. And slowly, carefully, she built something.

The arts are always in crisis. This is not new. But the current crises — of funding, of attention span, of cultural memory — have a way of making serious artistry feel like an endangered species. And yet, when Dench appears, something shifts. For a moment, we remember what we’re losing if we let the craft fall away.

She is proof that the long game still matters.

At 90, she is still working — albeit more selectively — and still changing how we understand what an actress can be. In an industry that too often discards women after 40, she has redefined late style. In an ecosystem allergic to subtlety, she’s made minimalism magnetic. And in a world that insists on categorising us — dramatic or comic, stage or screen — she has wandered freely, obliterating borders.

But more than her roles, it’s her approach that has created space for others. She is not jealous of younger talent. She praises them. She watches them. She invites them in. This generosity is not theatrical; it’s ethical.

And yet she never makes it easy for them. She is, in her way, an accidental gatekeeper. Not because she excludes — but because she raises the bar. Anyone aspiring to the life she has lived must confront not only her greatness, but the path it took to get there. The hours. The humility. The discipline.

This is the quiet revolution of Judi Dench. Not in speeches, but in choices. Not in manifestos, but in presence. She has made it harder for the culture to reward laziness — and harder still for it to forget what greatness looks like.

She also reminds us that the arts, when properly valued, are not a luxury but a necessity. In every society, there are those who interpret, who translate, who empathise and echo. That’s what actors do — and what Judi Dench has done better than most. She has reflected us back to ourselves — sometimes flatteringly, sometimes not — and asked us to look more closely.

She once told a young actor: “Don’t act the part. Be the person. Make me believe you exist.”

That advice applies just as well to the industry itself. Make us believe you exist — with integrity, with rigor, with meaning. Give us stories that hold rather than manipulate. Give us the patience to care again.

We need Dench not only for her talent, but for the reminder that real opportunity isn’t about being in the right place at the right time. It’s about staying in the game long enough to earn your moment — and then using that moment to lift others.

There is something profoundly hopeful in this.

Because if someone like Judi Dench — born in 1934 in York, in a time before television, in a country still reeling from war — could become the most beloved actor of her generation without ever compromising her values, then perhaps it is still possible.

Perhaps the next Dench is out there now — in a cramped flat, reading Shakespeare out loud to no one, wondering if it will ever matter.

And perhaps, one day, it will.

VIII. The Final Bow: Stillness and Storm

My favourite Judi Dench performance? It’s actually not quite so well-known. It’s her rendition of Send in the Clowns by Stephen Sondheim.

She performed it during a revival of A Little Night Music in the mid-1990s at the National Theatre, and it is, simply, devastating. Dench doesn’t sing it with the technical perfection of a classically trained vocalist — that’s not the point. She speaks-sings it with such raw, controlled emotion that the pauses between the lines are almost as powerful as the words themselves. Every syllable is loaded with regret, affection, bitterness, and self-knowledge. It’s a masterclass in how a song can become a monologue.

What makes it so unforgettable is that Dench doesn’t perform the song — she performs Desirée’s heartbreak. When she sings “Isn’t it rich?” she doesn’t project — she almost whispers, as if the line has just occurred to her. And when she reaches “Well, maybe next year,” the irony is like a blade. In her hands, Send in the Clowns becomes not just a torch song, but a quiet, perfectly measured collapse — one that leaves the audience breathless and utterly undone.

All of this is why, in the end, it is not the accolades that define Judi Dench — though there are many — but the effect. She leaves a trail not of applause but of transformation.

To meet her, to watch her work, to speak with those who love her, is to enter a kind of moral weather system. You find yourself recalibrating — not just what you thought about acting, but what you thought about what it means to move through the world.

At 90, she does not insist on reverence. She rolls her eyes at sentimentality. She would, one suspects, be slightly horrified by all this fuss. “I just got on with it,” she’d probably say, and she wouldn’t be lying — but she’d be omitting the miracle of how she did so.

She got on with it while reimagining Shakespeare for new generations. She got on with it while elevating every actor lucky enough to share her stage. She got on with it while grieving, while laughing, while ageing in public. And she continues to get on with it — because for her, the work is never done. Not because she’s restless. But because she’s faithful.

Remember again the story she tells about being taken as a child to see her brothers perform Macbeth, and that one line which caught her ear: “What bloody man is that?” And something stirred. She was, she says, “bewitched.”

The word is perfect. She has never stopped being bewitched — by language, by mystery, by the need to tell stories. And in return, she has bewitched us.

If we are lucky, we will see her again — on screen, or on stage, or perhaps just walking down a street, where someone might do a double-take, unsure whether they’ve seen a person or a statue come to life.

In truth, she is both.