BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson looks at the career of the tech titan and asks what we can learn from his extraordinary success

It is a shame to begin on an ad hominem note but it must be admitted that of all our billionaires, Jeff Bezos bears the greatest resemblance to Dr. Evil. “Be nice to geeks,” Bill Gates once said, adding: “Chances are you’ll end up working for one”. He was pointing to a perennial underestimation of a certain kind of problem-solving type. He was likely referring to himself to some extent – but he might just as well have been referring to the Amazon and Blue Origin founder.

There’s always something of a juxtaposition between the man the tech CEO was and the man he has become. We all know that success engenders some form of internal transformation – and this is why we all want success. You see this with all the billionaires down the years, whatever the sector: suddenly, as the billions roll in, we get the confidence; the TV shine; the measured cadences that let you know there is nothing left to prove to anyone.

In Bezos’ case we also have the superyacht, the fiancée Lauren Sanchez who turned Zuckerberg’s head at the Trump inauguration, and the transition from the unglamorous world of e-commerce into his current incarnation as a Space Cowboy.

But who is Bezos really and what does his journey tell us about ourselves and our own careers? For this article we spoke with experts in business, politics and journalism to gauge Bezos’ contribution.

New Lexicon

Seated across from Lex Fridman, the thinking man’s tech podcaster – whose carefully measured questions often elicit philosophical musings from his guests – you certainly feel that Bezos is a man who is now used to success, though perhaps still can’t quite believe its scale. There’s a moment, mid-conversation, when Bezos leans in slightly, the edges of his mouth curling upward in that unmistakable, booming laugh that has launched a thousand memes. In another sign of confidence, Bezos is dressed in a simple green polo neck—a departure from the corporate uniform of his Amazon years.

His words are deliberate, his tone genial but confident. This is a man who has spent decades refining his understanding of the world—one calculated decision at a time. “I think people assume I’m an optimist,” he says, cheerfully. “But I think of myself as a realist. The world is messy, unpredictable, and you have to build systems that anticipate change.”

It’s a playbook that has defined his career, and taken him from a Wall Street analyst to the architect of one of the most influential companies on the planet. It’s probably the first thing that strikes the viewer about Bezos – what a clear thinker he is, and how articulate.

Those who have read Bezos’ letters to his shareholders, which are compiled in Walter Isaacson’s brilliant book Invent and Wander: The Collected Writings of Jeff Bezos, won’t be so surprised by that. In his introduction – the first thing you should read about Bezos – Isaacson writes that Bezos possesses “an unending curiosity that leads him to explore new realms,” and notes how he “remains, like Steve Jobs and Leonardo da Vinci, someone who can connect the arts and sciences.”

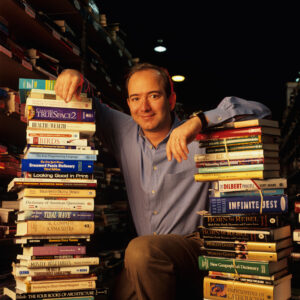

Those are some big names to be placed alongside, but the results – Amazon’s market cap is currently $2.11 trillion – won’t allow you to call it hyperbole. Besides, Bezos’s talent for connecting the arts and sciences is evident in Amazon’s literary origins as an online bookstore, where his technical innovation met his deep appreciation for literature. As Isaacson notes, “Bezos chose books as Amazon’s first product because there were millions of titles in print, far more than a physical store could stock.”

It was a masterstroke, and on many levels. James Badgett, the CEO of Angel Investment Network, has seen numerous entrepreneurs up close and has studied Bezos’ career closely. He tells me: “Bezos also understood that books were the one thing people would be most likely to buy online – he understood that a book is in a sense a trusted thing. And he never could have arrived at that insight without some sense of books – perhaps even a reverence for them.”

Great Scott

This intersection of commerce and culture was further enriched by his relationship with his first wife, MacKenzie Scott, a novelist who studied under the Nobel Prize winning Toni Morrison at Princeton. Morrison later praised Scott’s fiction as having “a rare power and elegance.”

AJ2MCF USA Washington Amazon com President Jeff Bezos with stacks of books inside huge warehouse in Seattle

Their partnership during Amazon’s formative years embodied this fusion of literary and technical worlds. What distinguishes Bezos as an intellectual entrepreneur is his ability to not merely execute business strategies but to conceptualize entirely new paradigms—creating what Isaacson calls “a flywheel that would disrupt multiple industries.” In a sense Bezos isn’t predominantly a technical innovator: what he does instead is to approach problems with a philosopher’s mindset, asking fundamental questions about human behaviour and desire. He then builds systems to address them.

The results are, appropriately for the founder of Blue Origin, out of this world. Consider the following, and try to imagine the extent of what has been achieved. As of 2024, Amazon generates over $500 billion in annual revenue, making it one of the world’s most valuable companies. The platform boasts over 300 million active customer accounts and processes more than 66,000 orders per hour. Amazon Web Services (AWS) alone contributes nearly $90 billion in revenue, powering a vast share of the internet. The company employs over 1.5 million people worldwide, and during peak shopping seasons like Prime Day and Black Friday, Amazon ships over a million packages per hour. With a global reach spanning over 100 countries, Amazon continues to revolutionize online shopping, cloud computing, and logistics at an unprecedented scale.

So how did he do it? Put another way, how did the man with the nervous geek giggle become the man with the billionaire’s laugh?

Back at the Ranch

Interestingly, in his conversation with Lex Fridman, Jeff Bezos reflects on the childhood experiences that shaped his problem-solving skills: “I spent all my summers on a ranch from age four to 16… I did all the jobs you would do on a ranch. I’ve fixed windmills, and laid fences, and pipelines, and done all the things that any rancher would do.”

Bezos is referring to the ranch of his maternal grandfather, Lawrence Preston Gise, who instilled in him his values and work ethic. Gise, a former regional director of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, retired to his 25,000-acre ranch in Texas, where a young Bezos spent countless summers immersed in the world of cattle, horses, and the challenges of rural life.

These formative experiences on the ranch left an indelible mark on Bezos, shaping his character and worldview in ways we need to understand.

“My grandfather was a self-reliant man,” Bezos recalled in a 2010 commencement speech at Princeton University. “He could fix anything, build anything. He taught me the value of resourcefulness and how to solve problems with limited resources.”

What’s important is that Bezos’s grandfather was not just a skilled handyman, he was also a meticulous planner – not to mention a man of unwavering determination. “He taught me to think big,” Bezos said in a 2018 interview with Forbes. “He always encouraged me to pursue my dreams, no matter how audacious they might seem.” This is good because his dreams were destined to be very audacious indeed.

On that ranch, it seemed as though no problem was permitted to be left unsolved. Bezos would later recall in a 2016 interview with The Washington Post, the newspaper he would later buy: “I helped fix windmills, vaccinate cattle, and do other chores. We also watched the Apollo moon landings on television together.” Let’s remember that this was the man who would later declare in 2019: “I want to build a spacefaring civilization. “We need to go to space to save Earth.”

2JBEJ46 1967 ca, USA : The celebrated american rich JEFF BEZOS ( Preston Jorgensen – born 12 january 1964 ) when was a young boy aged 3 . American entrepreneur, media proprietor , investor , computer engineer , and commercial astronaut . He is the founder, executive chairman and former president and CEO of AMAZON . Unknown photographer .- INFORMATICA – INFORMATICO – INFORMATICS – COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY – HISTORY – FOTO STORICHE – TYCOON – personalita da bambino bambini da giovane – personality personalities when was young – INFANZIA – CHILDHOOD – BAMBINO – BAMBINI – CHILDREN – CHILD – RICCO – RICH -. Image shot 1967. Exact date unknown.

The role of a mentor is transformative, but when that mentor is a family member—especially a grandparent—it’s as if the lessons take on a different weight. The difference between being mentored by a family member rather than an outsider is often one of depth and longevity—there is an unspoken trust, an inheritance of values that is absorbed as much through osmosis as instruction. It seems possible to speculate that had Bezos’ primary mentor not been a family figure, then Bezos might have gained professional insights but perhaps not the same deep, instinctive approach to problem-solving that defined his leadership. The emotional layer of mentorship within a family can create an unwavering confidence in one’s own abilities—a trait Bezos has carried into every venture – and which he would show in his early days at Amazon.

Confronting Gravity

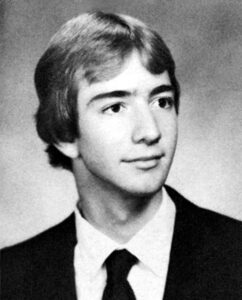

That was in the future. Initially, Bezos thought he would be a physicist. Bezos’ journey from aspiring physicist to e-commerce titan is a testament to the profound impact of self-awareness and pivotal encounters. While at Princeton University, Bezos grappled with a challenging partial differential equation for hours alongside his roommate, Joe. In their frustration, they sought help from their peer, Yasantha Rajakarunanayake, whom Bezos described as “the smartest guy at Princeton.” Upon presenting the problem, Yasantha glanced at it and promptly provided the solution, stating, “cosine is the answer.” This swift resolution left Bezos both astonished and introspective, leading him to realize, “That was the very moment when I realized I was never going to be a great theoretical physicist.”

This epiphany prompted Bezos to pivot towards computer science and electrical engineering, disciplines where he felt his strengths were better aligned. This decision laid the groundwork for his future ventures, including the founding of Amazon.

2M4KE2X 1981 ca, USA : The celebrated american rich JEFF BEZOS ( Preston Jorgensen – born 12 january 1964 ) when was a young teenager aged 17 , from HIGHT SCHOOL YEARBOOK . American entrepreneur, media proprietor , investor , computer engineer , and commercial astronaut . He is the founder, executive chairman and former president and CEO of AMAZON . Unknown photographer .- RITRATTO – PORTRAIT – INFORMATICA – INFORMATICO – INFORMATICS – COMPUTER TECHNOLOGY – HISTORY – FOTO STORICHE – TYCOON – personalita da giovani da giovane – personality personalities when was young – INFANZIA – CHILDHOOD – RAGA. Image shot 1981. Exact date unknown.

Badgett tells me: “Bezos’ experience underscores the importance of recognizing one’s limitations and adapting accordingly—a trait common among many successful individuals. In Bezos’ case, acknowledging that he might not excel as a theoretical physicist led him to a domain where his talents thrived, ultimately revolutionizing global commerce. This ability to pivot, informed by both personal insight and the recognition of others’ strengths, is a hallmark of adaptive and successful individuals.”

Founding a Behemoth

Fast forward to 1994 and Jeff Bezos, then a 30-year-old vice president at the hedge fund D.E. Shaw, made a pivotal decision that would forever alter the landscape of retail and technology. Since he has subsequently been so successful, we almost forget how inspired his decisions were; they seem inevitable in retrospect precisely because they’ve altered every aspect of our lives, and become so embedded.

Observing the rapid growth of internet usage, Bezos envisioned an online marketplace that could capitalize on this burgeoning medium. He identified a list of 20 potential products to sell online, ultimately deciding that books were the most logical starting point due to their universal demand and extensive selection.

With this vision in mind, Bezos resigned from his lucrative position and, along with Scott, embarked on a cross-country journey from New York to Seattle—a trip during which they refined the business plan for their nascent company. Operating out of their rented garage in Bellevue, Washington, they laid the foundation for what would become Amazon.

It’s often overlooked what a crucial role MacKenzie Scott played in Amazon’s early development. Drawing from her background in research and administration, she took on multiple responsibilities, including bookkeeping, writing checks, and negotiating the company’s first freight contracts. Brad Stone, an author who chronicled Amazon’s rise, noted, “She was clearly a voice in that room in those early years.”

One of the earliest and most significant challenges Amazon faced was securing adequate funding. Bezos invested a substantial portion of his own savings and sought investments from family and friends. His parents, Jackie and Mike Bezos, contributed approximately $300,000, despite the high risk involved. Bezos candidly warned them that there was a 70 per cent chance the company would fail.

We now know that they needn’t have worried. In July 1995, Amazon.com officially launched as an online bookstore. The response was overwhelmingly positive, with orders pouring in from all corners of the United States and beyond. This rapid growth, while encouraging, presented logistical challenges. The fledgling company had to adapt its operations quickly to meet the surging demand, often improvising solutions to ensure timely deliveries.

A pivotal decision during this period was Amazon’s commitment to reinvest profits into expanding its infrastructure and improving customer experience, rather than focusing on immediate profitability. This strategy allowed Amazon to scale rapidly and diversify its offerings, setting the stage for its evolution into a comprehensive online retail platform.

In 1997, Amazon went public, raising $54 million on the NASDAQ exchange. This infusion of capital enabled the company to further expand its product lines and invest in technology to enhance user experience. Bezos’s vision extended beyond books; he aimed to create a platform where customers could find anything they wanted to buy online.

Throughout these formative years, Bezos’s leadership was characterized by a willingness to take calculated risks and a relentless focus on customer satisfaction. He famously stated, “We’ve had three big ideas at Amazon that we’ve stuck with for 18 years, and they’re the reason we’re successful: Put the customer first. Invent. And be patient.”

Very often, MacKenzie Scott’s contributions extended beyond administrative duties. She was involved in brainstorming sessions and played a part in shaping the company’s culture and values. Her support allowed Bezos to focus on strategic initiatives, knowing that the company’s foundational operations were in capable hands.

“It’s not enough to succeed. Others must fail,” Gore Vidal once wrote. Many of the bookstores simply didn’t see it coming. Today in the UK, it can sometimes seem as though only one man in the books industry is holding out against it all.

Daunting Situation

James Daunt, the CEO of Waterstones, tells us that it’s been an uneasy accommodation. Despite the looming threat of Amazon to the book world, Waterstones has been “able to prosper” over the past ten years and sales have been gradually increasing. This, says Daunt, is mostly down to the experience created in-store, which remains the main point of differentiation between Waterstones and Amazon, with the latter providing neither customer-facing relations nor a warm “social” environment.

“Bookshops are nice places,” Daunt continues, “where you can find a book by recommendation or have the serendipity of picking up a book and thinking ‘Oh, I’ll read this’.” And the book you buy is “just better”. “I truly believe that there’s pleasure in walking out of a bookshop with a bag and feeling the weight of the book. You feel kind of virtuous – like you’ve almost read it.”

Badgett agrees with this adding: “You’re going to see this in many sectors. Retail outlets have to create experiences for customers or else they will perish – and they’ll perish precisely because Bezos is so successful at creating a streamlined customer experience.”

If Daunt had to point out the most important ingredient of bookshops, it would be the people. If at the start of the 21st century everything was about “cutting costs and getting rid of staff”, the past decade has been marked by reinvesting in the people of the industry. “The personality of your shop is, at the end of the day, embedded in your staff. If you invest in knowledgeable people who care about what they do, you’ll run a much better bookshop: this is what underpins the strength of Waterstones.”

And of course, this is another differentiator with Amazon, which has, in the past, been criticised for bad customer relations.

Waterstones dominates a quarter of the book market, and has been able to thrive in recent years. But what of smaller independents, who collectively hold a mere 3 per cent share of the market? “The good ones are actually in a better position than chains like Waterstones,” Daunt says, pointing to the backing such shops receive from their local communities. And again, it’s “survival of the fittest”: “If you’re good enough, and you genuinely create a nice environment, you’ll be fine. The rise of Amazon actually weeded out all the weak ones, and it’s the good ones that remain,” Daunt argues.

Even so Daunt is realistic about what’s achievable in the age Bezos has created. “The market share is tiny, because at the end of the day Amazon will always undercut. They invest much more, and they’ll always have the advantage of having created the market in the first place. Everybody else is just playing catch up.”

In other words, the only way to compete with Bezos is in some way to imitate him – to become swifter, smarter and more decisive. Daunt has also said that it was important to the success of Waterstones to put the Kindle in the shop to demystify it and make sure the staff weren’t afraid of it.

Of course, it hasn’t all been rosy for Amazon. Throughout his career, Bezos has demonstrated an unusual tolerance for failure as part of the innovation process. After the spectacular flop of the Fire Phone, he famously remarked, “If you think that’s a big failure, we’re working on much bigger failures right now.”

This perspective transforms apparent contradictions into competitive advantages, allowing Bezos to pursue high-risk, high-reward opportunities that more conventionally minded business leaders might avoid.

Even so the overwhelming trajectory is one of success – and a success hardly paralleled in human history. The question then is: “What business philosophy underpins his achievements?”

Thought Leader

I speak with Dr. Paul Hokemeyer, a clinical and consulting psychotherapist, who offers a psychological perspective on Bezos’ leadership style. I remind him that Bezos makes a distinction between hiring ‘missionaries’ over ‘mercenaries’, with an obvious preference for the former. This seems wise to me but often in HR processes we don’t know what we’re being presented with. How do these different types – those who are just in it for the salary and true believers in a company, often present at first?

“What Bezos is talking about here is character,” Hpkemeyer explains. “Character manifests relationally over time. In this regard, missionaries are people who are invested in ideological outcomes and long-term relationships. They stand in contrast to people who are transactional, focused on zero-sum wins and self-advancement.”

It’s clear he finds Bezos’ perspective intriguing, but he also sees the challenge in identifying these qualities at first glance. “HR executives who want to find these people need to study candidates through these two lenses,” he explains. “They need to engage in due diligence to see what the person has invested their time, energy, and capital in and how they manifest themselves relationally over time.” The distinction, he suggests, isn’t always immediate. People don’t walk into an interview labelled as either missionaries or mercenaries—these differences only become apparent when you observe how they interact, what they prioritise, and how they respond under pressure.

The conversation shifts naturally to Bezos’ framework for decision-making—the ‘one-door’ decisions that are high-stakes and irreversible, and the ‘two-door’ decisions that can be undone with minimal cost. Hokemeyer says: “Human beings are relational creatures. We orient ourselves according to similar traits, interests, and goals. While this provides a sense of security, it also subjects us to biases and limits our creativity,” he says. Bezos’ two-door decisions, he explains, represent this tendency towards safety and familiarity. “They reflect safe and familiar decisions but do not push creative boundaries. They are also subject to limitations. Think of lemmings who follow each other over a cliff. In the realm of psychology, this is referred to as ‘groupthink’. In it, people prioritize group harmony over critical thinking. Too often, this type of thinking leads to irrational and even harmful decisions. As such, they need to be considered thoughtfully.”

One-door decisions, however, require a different mode of thinking. “These decisions are based on reduction, induction, and deduction. Through them, a person analyses complex data and simplifies and derives conclusions from observation and generalized principles. People can advance existing knowledge to higher and better states through such a process.” He adds: “The best leaders know when to lean into each type of decision-making. They don’t just follow instinct—they create structures that allow for clarity.”

Bezos’ success is no accident. The Princeton graduate who left a high-powered hedge fund job to sell books online didn’t stumble into greatness—he engineered it. His approach has always been methodical, his belief in long-term vision unwavering.

“We don’t make decisions at Amazon with slides,” he reveals. “We do it with six-page memos. Everyone reads them, and then we debate.” The process is about achieving clarity, stripping away unnecessary fluff. “If the memo isn’t great, the meeting doesn’t happen. If it is great, we rip it apart and make it better.” It’s a relentless pursuit of improvement, a refusal to let stagnation creep in.

Referring to the memo approach, Hokemeyer explains: “Bezos has been a genius at reinventing the industry, maximizing customer service, and capturing market share,” he says. “His approach focuses on experimenting and breaking from conventional thinking, encouraging leaders to think big and pursue unconventional solutions. So, starting with an articulate memo and then engaging in a relational exercise to tear it apart to make it better is very much a part of his ethos.”

He links this back to the neuroscience of problem-solving. “From a neurophysiological standpoint, he harnesses the brain’s capacity to make order out of chaos and, in so doing, builds better and better mousetraps.” The balance between structure and creative disorder is, in Hokemeyer’s view, a significant driver of innovation.

The Wonder of the Wander

Our discussion turns to Bezos’ belief in ‘wandering’—the ability to allow thoughts to drift, to embrace the unexpected, to step outside the rigidity of structured work. This, too, has deep historical roots. “The notion of the creative wanderer is grounded in the writings of Charles Baudelaire, a poet who wrote during the Age of Enlightenment,” Hokemeyer explains. “Baudelaire wrote of the ‘flâneur’—a person who would aimlessly wander the streets of Paris, looking for creative inspiration through sensory and intellectual observation.”

It’s an elegant comparison. “Bezos is a pioneer in the second wave of enlightenment, wherein new technological advancements can be used to improve the human experience. For businesses seeking to replicate their work in the realm of ‘technological flânerie,’ companies must be mindful of providing workspaces where employees can go and just be—or encouraging them to go out in their local communities and wander whilst drinking in the immediate ethos of the environment.”

But can too much wandering lead to a lack of urgency? Hokemeyer disagrees. “This work should be seen not as the exclusion of task and goal-oriented work but as an integral part of it.” He suggests that companies should actively build time for exploration into their structures rather than treat it as an afterthought.

Always at the centre of Bezos’ story is this ability to think round problems. Badgett points to this as one of Bezos’ defining strengths. “He understands that most entrepreneurs make the mistake of not making the funnel wide enough. What Bezos does is make sure every step of the customer experience is frictionless. It’s deceptively simple but incredibly hard to execute.” Perhaps other organisations don’t wander enough.

Global River

Bezos’ career is a mosaic of bold decisions, relentless execution, and a willingness to be misunderstood for long periods of time. Amazon was dismissed as an internet bookstore before it became a trillion-dollar behemoth. Amazon Web Services (AWS) was once seen as a side project before it evolved into the backbone of the modern internet. Prime, Alexa, Kindle—all ideas that were initially ridiculed before they redefined their industries.

Amazon’s global expansion strategy has been marked by both significant investments and notable challenges across various regions, particularly in India and China.

In India, Amazon has demonstrated a robust commitment to establishing a substantial presence, with Hyderabad emerging as a focal point of its operations. In 2019, Amazon inaugurated its largest campus globally in Hyderabad, spanning 9.5 acres and designed to accommodate over 15,000 employees. Amazon’s investment has contributed to the city being labelled Cyberabad. I happen to have been there, and remember its offices rising out of the glorious excitement of modern India, as if it were somehow presiding over the next period of history.

This facility underscores Amazon’s dedication to the Indian market and its intent to leverage the country’s burgeoning tech talent. Akhil Saxena, Amazon’s Vice President of Global Customer Fulfillment, remarked during the campus inauguration, “This campus is also a tangible commitment to our long-term thinking and our plans for India.”

Further solidifying its investment in the region, Amazon Web Services (AWS) announced plans in March 2025 to invest approximately $8.2 billion in the Indian state of Maharashtra over the next few years. This investment aims to bolster local cloud data storage capabilities and support the rapidly growing cloud services market in India, which is projected to reach $24.2 billion by 2028. It is another sign of the scale of Bezos’ thinking. Ashwini Vaishnaw, India’s Minister of Electronics and Information Technology, highlighted the broader impact of this investment, stating, “Along with the investment, there will be significant growth in employment.”

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has engaged with Amazon’s leadership, notably meeting with CEO Andy Jassy on June 23, 2023, in Washington, D.C. During this meeting, discussions centered on e-commerce, digitization efforts, and the logistics sector in India. Amazon announced plans to invest an additional $15 billion in India by 2030, bringing its total investment in the country to $26 billion.

Bezos hasn’t had it all his own way. Amazon’s journey in China has been fraught with challenges, leading to a strategic retreat from the domestic e-commerce market. Despite early ambitions, by 2019, Amazon’s market share had dwindled to a mere 0.6%, prompting the closure of its local marketplace operations. Industry analysts attribute this outcome to fierce competition from local e-commerce giants like Alibaba and JD.com, as well as Amazon’s struggle to adapt to local consumer preferences and regulatory landscapes.

Jack Ma, co-founder of Alibaba, has previously delineated the fundamental differences between the two companies’ business models, emphasizing that Alibaba’s role is to empower others to engage in e-commerce, whereas Amazon operates as a direct e-commerce entity. Ma stated, “Amazon and eBay are e-commerce companies, and Alibaba is not an e-commerce company. Alibaba helps others to do e-commerce. We do not sell things.”

Reflecting on the broader responsibilities of tech giants, Ma also commented, “Google, Facebook, Amazon, and Alibaba—we are the luckiest companies of this century. But we have the responsibility to have a good heart and do something good.”

Interestingly, there is no public record of Chinese President Xi Jinping making direct comments about Amazon. However, in 2019, the Chinese government requested that Amazon remove customer reviews and ratings for President Xi’s book, “The Governance of China,” on its Chinese platform. This move came after negative reviews appeared on the site, leading Amazon to disable the comments section for the book. A source familiar with the matter noted, “I think the issue was anything under five stars.”

Despite these regional complexities, Amazon’s overarching vision remains unchanged: a commitment to long-term thinking and continuous reinvention. But as the company expands into new markets and navigates shifting regulatory landscapes, its internal structures must evolve to keep pace. This is where Amazon Circles comes into play—an organizational experiment designed to maintain agility while scaling the company’s decision-making processes.

Squaring the Circle

A radical departure from corporate hierarchy, Amazon Circles is built on decentralized decision-making, empowering small teams to innovate without bureaucratic bottlenecks. Much like AWS reshaped cloud computing, Circles aims to create a flexible, networked model of management. This reflects Bezos’ belief that Amazon must always be a “Day One” company—nimble, customer-focused, and resistant to stagnation.

Circles is Amazon’s latest attempt to balance scale with the start-up energy that drove its early breakthroughs. Just as AWS and Prime redefined their industries, Circles seeks to reshape corporate structure itself, fostering an environment where bold ideas can emerge from any level, rather than trickling down from the top.

Amazon, the e-commerce juggernaut delivering everything from diapers to drones, has a secret weapon: Circles. These Circles are self-organizing teams—an agile framework quietly fuelling Amazon’s relentless growth and customer obsession. Imagine Lord of the Rings, but instead of hobbits on a quest for a ring, it’s software developers chasing the ultimate customer experience.

The model is deceptively simple. A Circle typically consists of 8-10 employees from various departments, united by a shared goal. They meet, brainstorm, and implement solutions collaboratively. Hierarchy dissolves—ideas win regardless of job title. Picture a marketing manager, a software engineer, and a warehouse worker debating the best way to deliver dog biscuits. That’s Circles in action.

“Circles have been instrumental in fostering a culture of ownership and accountability,” says Dave Clark, former SVP of Worldwide Operations at Amazon. “They empower employees to think big, take risks, and drive meaningful change.” Jeff Wilke, former CEO of Worldwide Consumer, echoes this: “Circles allow us to move faster, be more agile, and respond to customer needs with greater speed and efficiency.”

Amazon’s approach to organization balances agility, innovation, and relentless customer focus. Central to this is the “Two-Pizza Rule”: teams should be small enough to be fed with two pizzas. This principle underpins Amazon’s decentralized model, ensuring that innovation happens at a pace large bureaucratic organizations can’t match.

A key strength of Circles is their amplification of customer obsession. By integrating employees across departments, these teams ensure that every decision is customer-centric. Instead of top-down mandates, Circles act as built-in focus groups, constantly refining the customer experience.

This culture of experimentation pushes employees to challenge convention and develop creative solutions. Jeff Wilke notes that this flexibility is Amazon’s competitive advantage: “Circles allow us to move faster, be more agile, and respond to customer needs with greater speed and efficiency.” Unlike traditional corporations bogged down by hierarchical approval chains, Circles empower employees to act decisively, keeping Amazon adaptable in a shifting digital landscape.

Circles also boost employee engagement. By giving individuals direct influence over decisions, Amazon fosters a culture of ownership. Employees don’t just execute orders—they shape their teams’ direction. This has created what some describe as a company filled with “mini-CEOs,” each responsible for their domain.

No system is without its challenges. The decentralized structure requires careful oversight to maintain focus and ensure alignment with broader company goals. Without strong leadership, teams risk drifting from Amazon’s strategic vision. Yet when managed well, this approach has allowed Amazon to retain the agility of a startup while scaling into a global empire.

So next time you marvel at Amazon’s speed and efficiency, remember the Circles. These self-organizing teams are the silent architects of Amazon’s success, proving that the future of innovation belongs not to rigid hierarchies, but to those who empower individuals, foster collaboration, and remain obsessively customer-focused. They are the unsung heroes of Amazon’s meteoric rise—quietly revolutionizing the way we think about work.

Jass Hands

In July 2021, Jeff Bezos stepped down as CEO of Amazon, a moment that carried immense symbolic weight—not just for the company, but for the entire tech industry. For 27 years, Bezos and Amazon were inseparable. So what did it mean for Amazon?

Stepping into the role of CEO was Andy Jassy, a figure well-versed in Amazon’s culture and operations. Having played a pivotal role in the creation and success of Amazon Web Services (AWS), he was no stranger to the company’s relentless pace of innovation. His appointment ensured continuity, yet any leadership transition at this scale comes with uncertainty. Investors, employees, and analysts alike speculated—would Amazon maintain its aggressive expansion under new leadership? Could Jassy match Bezos’ visionary drive?

For Bezos, stepping aside as CEO did not mean stepping away. Instead, it allowed him to shift focus toward new ambitions, particularly Blue Origin, his space exploration venture, and various philanthropic initiatives. As executive chairman, he retained a strategic role, ensuring that his influence would still shape Amazon’s future. But with Bezos redirecting his energy, a key question loomed: What would Amazon become without him at the helm?

The media and markets took notice. Analysts debated whether Amazon’s meteoric rise could continue under Jassy. Competitors watched closely, evaluating whether the company’s aggressive expansion would wane. The moment transcended a routine leadership change—it was an inflection point that forced the world to reassess what Amazon truly was, beyond its iconic founder.

When Andy Jassy officially took the reins in July 2021, he inherited an empire built on the foundations of relentless innovation. Having joined Amazon in 1997, he had spent decades cultivating an understanding of the company’s DNA. His leadership of AWS—Amazon’s cloud computing arm—had transformed it into a revenue powerhouse, shaping the internet as we know it. But leading AWS was one thing; leading Amazon as a whole was another.

As CEO, Jassy not only championed AWS’s continued dominance but also pushed Amazon into new industries, expanding its technological and retail footprint. Under his leadership, AWS continued its rapid evolution, introducing new services such as Amazon Connect, a cloud-based contact center, and Amazon Honeycode, a no-code app builder, while expanding its reach into key sectors like healthcare and the public sector. These invevntions haven’t yet entered the public consciousness to the same extent as achievements under Bezos, but it’s early days.

Beyond cloud computing, Jassy has driven Amazon’s expansion into healthcare. His oversight of Amazon Care, a telehealth initiative, demonstrated the company’s ambitions in the sector, and though it was ultimately shut down, it provided valuable insights for future healthcare ventures. The $3.9 billion acquisition of One Medical further signaled Amazon’s commitment to disrupting traditional healthcare models.

The advertising sector has also flourished under Jassy’s leadership. Recognizing the power of Amazon’s vast customer data, he has overseen explosive growth in advertising revenue, making it one of the company’s fastest-growing profit centers. This revenue stream has, in turn, fuelled investments in logistics, technology, and new business verticals.

Amazon’s logistics and fulfilment networks have been another priority. Expanding its delivery infrastructure has allowed for faster shipping times, better inventory management, and a competitive edge against traditional retailers. Under Jassy, Amazon has reinforced its supply chain dominance, ensuring that it remains a step ahead in the evolving e-commerce landscape.

Strategic acquisitions have also played a major role in Jassy’s leadership. The $8.5 billion purchase of MGM Studios added a vast library of content to Amazon Prime Video, strengthening its position in the streaming wars. Meanwhile, the company’s grocery expansion, through initiatives like Amazon Fresh and Amazon Go, underscores a broader push to diversify its retail presence beyond e-commerce.

Despite these successes, Jassy’s tenure has not been without challenges. Amazon has faced increased regulatory scrutiny, labor disputes, and supply chain disruptions, all while navigating a post-pandemic economy. In response, Jassy has emphasized transparency, employee well-being, and corporate responsibility, committing Amazon to sustainability initiatives and local community investments.

As CEO, Jassy is not merely maintaining Amazon’s legacy—he is actively reshaping its future. His leadership is defined by an intricate balance: preserving Bezos’ innovative ethos while carving out his own strategic vision. Whether steering Amazon deeper into cloud computing, healthcare, logistics, or entertainment, Jassy’s approach ensures that the company remains a global force, continuously evolving with the digital age.

The transition from Bezos to Jassy was more than a change in leadership; it was a signal of Amazon’s next phase. While Bezos built the empire, Jassy is now tasked with reinventing it for the future—a challenge that will define Amazon’s trajectory in the years to come.

And Bezos? He would go interstellar. For him, success was never just about selling books, or even about retail—it was about solving problems at scale. His entire career has been a case study in thinking beyond the immediate, building not just for the next quarter, but for the next century. If Amazon was about making commerce frictionless, his next great challenge was something even more ambitious: securing humanity’s long-term future.

Bezos has often spoken of Earth as a ‘garden world’ that should be preserved, not overexploited. But preservation requires an alternative—a place for heavy industry, for expansion, for growth beyond planetary limits. If Amazon was about reimagining retail, Blue Origin was about reimagining our place in the cosmos. And so, in 2000, long before private spaceflight was fashionable, Bezos quietly founded the company that would become his most audacious venture yet.

Shalini Khemka CBE, founder of the E2E network tells me: “Bezos is very passionate about space and science and doing things which are pretty extraordinary like Elon Musk is. So he does. He’s a man who follows his passions. You know, the businesses come out of passion, passionate interest.”

Prime Cosmos

They certainly do. But while Elon Musk and SpaceX aggressively pursued interplanetary travel and Mars colonization, Bezos took a different approach. He envisioned a future where millions of people could live and work in space, but instead of focusing on Mars, he looked towards developing infrastructure that could support a broader space economy. He was particularly inspired by the concepts of physicist Gerard K. O’Neill, who proposed massive orbiting space stations that could sustain human life indefinitely.

To achieve this vision, Bezos focused on building reusable rocket technology, believing that the key to unlocking space was to lower costs dramatically. Blue Origin’s motto, “Gradatim Ferociter” (Step by Step, Ferociously), encapsulated this philosophy.

Blue Origin, founded by Bezos in 2000, was never just a passion project—it was an attempt to redefine humanity’s relationship with space. From the outset, Bezos spoke in grand terms about the future, imagining a world where “millions of people can live and work in space.” But space is unforgiving, and progress has been anything but smooth, as we shall see.

But in entering this sector, is he really so different from Musk? “In one sense he is similar,” Khemka adds. “Especially by this stage, he’s not thinking about, can I make money? He’s thinking about, what is it that I want to change? What is it that I want to build or disrupt? Or where is the problem in the world, and how can I help to solve that problem and the money comes afterwards. He is obviously hugely commercial, but I don’t think it’s driven by commerciality. I think it’s driven by making a difference – effecting change.”

3AN9GYR United States. 14th Apr, 2025. Blue Origin founder Jeff Bezos poses with (from left) film producer Kerianne Flynn, popstar Katy Perry, Lauren Sanchez (Jeff Bezos’ fiancee), former NASA rocket scientist Aisha Bowe, journalist Gayle King, and bioastronautics researcher Amanda Nguyen, after the all-female crew landed in West Texas after Blue Origin completed its 11th human spaceflight and the 31st flight of its New Shepard program on Monday, April 14, 2025. Photo via Blue Origin/UPI Credit: UPI/Alamy Live News

It’s good that the motivation is strong because setbacks have inevitably come, along with some crucial successes. The company began its journey with cautious steps, testing suborbital rockets long before attempting anything more ambitious. In 2006, the Goddard prototype completed a brief but promising test flight, proving the company’s ability to launch and land vertically—an idea that would later become fundamental to commercial spaceflight. By 2015, Blue Origin made history with New Shepard, a suborbital rocket that successfully launched, reached space, and then performed a controlled vertical landing. This was a triumph, a tangible demonstration of the company’s belief in full reusability as the key to reducing launch costs.

Yet while New Shepard has carried paying customers—including Bezos himself—on brief, suborbital joyrides, the broader ambition of competing with SpaceX has been less straightforward. New Glenn, Blue Origin’s answer to Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy, has been beset by delays. First announced in 2016 with a planned 2020 launch, the rocket has yet to complete a fully successful flight. The first test mission, in early 2025, reached orbit, but the booster failed to land on the recovery ship, a stark reminder of the difficulty of engineering fully reusable rockets.

The rivalry with Elon Musk has been an unavoidable subplot. The two billionaires, both obsessed with the future of spaceflight, have exchanged pointed remarks over the years. Musk, whose SpaceX has dominated the industry with rapid iteration and frequent launches, has been dismissive of Blue Origin’s slow pace. When Bezos announced his lunar lander project, Blue Moon, Musk tweeted, “Oh stop teasing, Jeff.” When asked about Blue Origin’s progress in an interview, he responded simply, “Jeff who?” Bezos, for his part, has been more measured but has taken legal action against NASA’s decision to award key contracts to SpaceX over Blue Origin, prompting further digs from Musk, who derided Blue Origin as a company that “sues instead of innovates.”

Even so, the Astronomer-Royal Martin Rees is among those cheering him on, telling me: “Space travel is very expensive. For that reason, if I was an American taxpayer or European taxpayer I wouldn’t support NASA’s or ESA’s programs for manned space flight. On the other hand, I’m prepared to cheer on the endeavours of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk in the private sector. Firstly, they’re not using taxpayers’ money, and secondly, they can take higher risks than NASA or ESA can when sending civilians into space.”

Blue Origin has continued pushing forward. The company has secured a role in NASA’s Artemis program with the Blue Moon lander, and its New Glenn rocket—though delayed—will eventually provide another option in the growing launch market. More recently, Blue Origin announced an all-female crewed mission featuring Katy Perry and Lauren Sánchez, a move that captured public interest and showed that, while Blue Origin may not be moving at the breakneck speed of SpaceX, it is still shaping the conversation around commercial space travel.

It is easy to dismiss Blue Origin as the slower, more corporate cousin to SpaceX, but its methodical approach has its merits. Bezos has always maintained that space is a long game, and while Musk may be launching rockets at an astonishing rate, history will judge not just who moved fastest, but who built something that lasts. For now, the race continues—one billionaire flying higher, the other still quietly plotting his ascent.

That’s certainly an expansive perspective—and it explains his significant personal investment in Blue Origin, which he has called his “most important work.” Bezos has funded this space venture by selling Amazon stock worth billions, demonstrating his willingness to convert present wealth into future possibilities. “The only way that I can see to deploy this much financial resource is by converting my Amazon winnings into space travel,” he once explained. His fascination with long-term thinking is equally evident in his $42 million contribution to the Clock of the Long Now, a mechanical timepiece designed to run accurately for 10,000 years.

It might even be said Bezos has long been preoccupied with projects that stretch beyond the limits of a single human lifetime. Whether it’s space travel, renewable energy, or artificial intelligence, his vision consistently leans toward endeavours that demand patience, resilience, and an understanding that the most significant rewards often lie far beyond the present. It is this same philosophy that underpins one of his most enigmatic and ambitious projects—one that is not about rockets or commerce, but about time itself.

The Other Tick Tock

The Clock of the Long Now is deep in the heart of Texas, nestled within a remote mountain range. This monumental timepiece is designed to tick for 10,000 years, and Bezos has been crucial in bringing this ambitious project to fruition.

The Clock of the Long Now is not your average timekeeping device. It is a complex mechanical marvel, designed to withstand the test of time and serve as a reminder to future generations to think beyond the immediate.

The clock’s gears, crafted from stainless steel and marine bronze, are designed to move slowly and deliberately, marking the passage of time with a sense of gravity and permanence.

The clock’s location, deep within a mountain, is no accident. It is meant to be a place of pilgrimage, a destination that requires effort and intention to reach. The journey to the clock is as much a part of the experience as the clock itself, a reminder that long-term thinking requires patience, dedication, and a willingness to look beyond the horizon.

Bezos’s involvement in the Clock of the Long Now is a reflection of his own philosophy.

He has often spoken about the importance of long-term thinking in business and in life. In a 2019 letter to Amazon shareholders, he wrote, “If everything you do needs to work on a three-year time horizon, then you’re competing against a lot of people. But if you’re willing to invest on a seven-year time horizon, you’re now competing against a fraction of those people, because very few companies are willing to do that.”

The Clock of the Long Now is a reminder that we are part of a larger story, a story that stretches far beyond our own lifetimes. It is a call to consider the long-term consequences of our actions and to make decisions that will benefit future generations.

As Bezos himself has said, “If you extend your time horizon out, remarkable things can happen.” The Clock of the Long Now is a testament to this belief, a monument to the power of long-term thinking and the enduring legacy of human ingenuity.

In our digital age where innovation cycles are measured in months, Bezos’s support of the Clock represents something deeply countercultural. This timepiece challenges our collective short-term thinking. Bezos understands that civilization depends on extended contemplation. The most important projects require timeframes that most corporate boards would find unimaginable. The Clock’s steady mechanism marks time differently. It suggests that humanity’s greatest achievements come from those who plant forests they’ll never sit beneath. By funding this strange timepiece, Bezos has created a perfect metaphor for his business approach. He’s willing to endure Wall Street’s confusion while building enterprises designed to outlast him. In this steel chronometer, we see not just Bezos the entrepreneur, but Bezos the philosopher. The Clock offers a meditation on mortality and the meaningful pursuits that transcend it.

Bezos’s invitation to expand our temporal horizons works in both directions. By challenging us to contemplate millennia ahead, the Clock of the Long Now also prompts reflection on the continuum connecting past, present, and future. Just as the Clock’s mechanism traces time forward in measured increments, we can better understand Bezos’s visionary perspective by tracing backward through his formative experiences.

The seeds of his long-term thinking, comfort with uncertainty, and boundless curiosity were planted decades before Amazon’s founding. But if time is the first frontier, thought is the next. For Bezos, space is not the only unexplored territory worthy of investment—ideas, and the institutions that shape them, demand careful cultivation too. His entry into journalism was not merely the indulgence of a billionaire collector but a deliberate move into the contested arena of knowledge itself. Just as his rockets seek to propel humanity beyond Earth’s constraints, his stewardship of the Post suggests a similar ambition for the marketplace of ideas.

Post script

In August 2013, Jeff Bezos made a decision that surprised many: he purchased The Washington Post for $250 million. At the time, the move seemed incongruous for the billionaire founder of Amazon, a tech mogul whose career had been defined by e-commerce, logistics, and cloud computing.

Yet, in hindsight, Bezos’ acquisition of the legendary newspaper was not just an investment in a struggling media outlet but a calculated decision that would shape the future of journalism in the digital age. His entry into the media world influenced the paper’s financial model, technological infrastructure, and editorial independence. To fully understand the ramifications of this acquisition, it is essential to place it within the historical context of the newspaper and the challenges facing journalism at the time.

Founded in 1877, The Washington Post began as a modest four-page daily newspaper in the nation’s capital. Over the years, it grew into one of the most influential newspapers in the United States, playing a pivotal role in shaping American journalism. Under the leadership of publisher Katharine Graham and legendary editor Ben Bradlee, the paper gained national prominence in the 20th century, particularly during the Watergate scandal. Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s investigative reporting on the Nixon administration’s corruption led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon in 1974, solidifying the Post’s reputation for fearless journalism.

However, by the early 21st century, The Washington Post, like many print newspapers, was struggling. The rise of the internet had eroded traditional revenue streams as readership declined and advertising dollars shifted to digital platforms like Google and Facebook. Circulation was plummeting, and the Post faced significant financial difficulties. It was in this turbulent media landscape that Jeff Bezos stepped in, purchasing the paper from the Graham family, who had owned it for four generations.

For Bezos, the acquisition of The Washington Post was not a random indulgence but a strategic move driven by several factors. While some speculated that his motives were political or personal, Bezos himself stated that his decision was based on his belief in the newspaper’s critical role in democracy and his conviction that he could help reinvent its business model.

One of Bezos’ primary reasons for buying the Post was his understanding of digital transformation. As a pioneer in e-commerce and cloud computing, he recognized the need for legacy media to evolve in the internet age. He saw an opportunity to apply Amazon’s principles of customer obsession, data-driven decision-making, and technological innovation to a newspaper that was struggling to adapt to digital trends.

Additionally, Bezos had a long-standing interest in journalism. As a child, he was an avid reader of newspapers, and he understood their value in shaping public discourse. His acquisition of the Post was not just an investment in a media outlet but in an institution he saw as vital to democracy.

Bezos’ impact on The Washington Post was profound. From the outset, he took a hands-off approach to editorial decisions, pledging to uphold the newspaper’s independence. Instead of interfering in the newsroom, he focused on modernizing its business operations, expanding its reach, and leveraging technology to improve efficiency and profitability.

One of his first moves was to invest heavily in technology and digital infrastructure. Under his ownership, The Washington Post developed its own publishing platform, Arc XP, which improved the paper’s online user experience and became a revenue-generating product used by other media companies. Bezos also introduced a subscription-based model similar to Amazon Prime, increasing digital subscriptions from under 100,000 in 2013 to over 3 million by 2020. This shift was critical in ensuring financial sustainability, as advertising revenue alone was no longer sufficient to sustain major newspapers.

Another key change was the expansion of The Washington Post’s coverage. Under Bezos, the paper transitioned from a primarily Washington-focused publication to a national and even global news powerhouse. He hired new journalists, expanded investigative reporting, and invested in data-driven journalism. The Post’s reporting became more ambitious, covering not just politics but technology, science, and global affairs with greater depth and resources.

In 2025, Bezos posted a tweet explaining that he was asking the opinion section to write in defence of freedom and free markets, triggering the resignation of long-standing opinion editor David Shipley. Reaction to this fell along political fault lines. Here in the UK, Baron Young of Acton tells me: “I think it’s smart of Jeff Bezos to shift the Washington Post’s editorial line to defending freedom. Left-of-centre legacy media brands have been in freefall since last November because their customers have lost trust in them and unless they can rebuild that trust they’ll go out of business.”

But whatever the controversies the financial position under Bezos is clear: in that sense things have improved dramatically. Once struggling to stay afloat, the Post became profitable again, allowing it to reinvest in journalism rather than cutting costs, as many other newspapers were forced to do.

Bezos’ success in turning around the Post encouraged other newspapers to rethink their strategies, with more outlets embracing subscription models and technological innovations to sustain their businesses. The New York Times, for example, expanded its digital-first approach, inspired in part by the Post’s resurgence.

As The Washington Post continues to evolve, Bezos’ influence will remain a defining feature of its modern history. Whether his legacy will ultimately be seen as a savior of journalism or a harbinger of increasing corporate control over the press is a question that will likely continue to be debated for years to come.

Future proofing

For Bezos, success was never just about selling books, or even about retail—it was about solving problems at scale. His entire career has been a case study in thinking beyond the immediate, building not just for the next quarter, but for the next century. If Amazon was about making commerce frictionless, his next great challenge was something even more ambitious: securing humanity’s long-term future.

Bezos has often spoken of Earth as a ‘garden world’ that should be preserved, not overexploited. But preservation requires an alternative—a place for heavy industry, for expansion, for growth beyond planetary limits. If Amazon was about reimagining retail, Blue Origin was about reimagining our place in the cosmos. And so, in 2000, long before private spaceflight was fashionable, Bezos quietly founded the company that would become his most audacious venture yet.

This instinct for long-term vision is deeply embedded in the culture he has built. Shalini Khemka, founder of the E2E network, reflects on this: “What Jeff has instilled within Amazon is the start-up mentality. Despite being a multi-billion-pound company, its divisions—AWS, Amazon Prime, and their subdivisions—are structured to think like startups. They are encouraged to be creative, nimble, and to operate with the urgency of a company still proving itself.”

James Badgett, CEO of Angel Investment Network, takes this further: “Bezos understands that success is not just about scale, but about resilience. He has built systems that allow for constant reinvention. Amazon doesn’t just react to change—it anticipates it. That’s why his impact will extend far beyond e-commerce.”

Bezos’s invitation to expand our temporal horizons works in both directions. By challenging us to contemplate millennia ahead, the Clock of the Long Now also prompts reflection on the continuum connecting past, present, and future. Just as the Clock’s mechanism traces time forward in measured increments, we can better understand Bezos’s visionary perspective by tracing backward through his formative experiences.

In the end, Bezos is not merely an entrepreneur but an architect of possibility. He builds systems, not for the present, but for futures yet to unfold—whether in the algorithms of e-commerce, the circuits of digital media, or the silence of deep space. As he told Lex Fridman, ‘We are the lucky ones who get to lay the foundation stones for a future we will never see.’ It is this relentless drive—this refusal to settle for mere success—that has defined his life’s work. And perhaps, long after the last Amazon package is delivered or the final rocket launches, it is this philosophy that will endure the longest.”