By Christopher Jackson

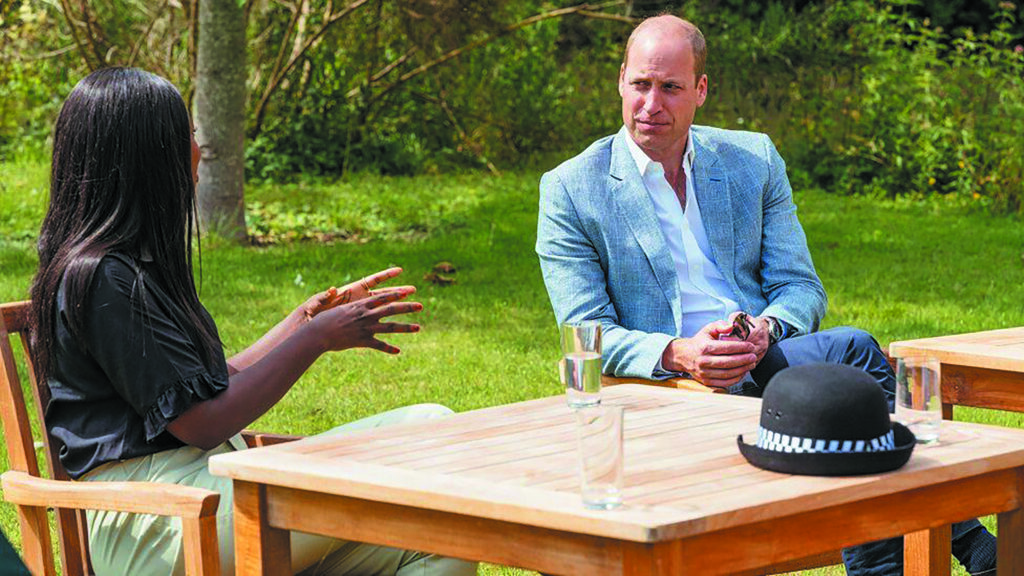

Consider this. The background at Kensington Palace looks no different to a luxury hotel. A fern behind Prince William’s blue-blazered right shoulder cedes to another plant over his right. Between The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, there is a picture which might be Prince George although the photograph blurs slightly – a suggestion of the room’s scale. Normally, in Zoom calls, in our smaller homes, you don’t have this kind of receding perspective. In the distance a mirror reflects back the high window which must be sitting ahead of the couple: it is a room full of light.

The Duke of Cambridge says: “Something I noticed from my brief spell flying the Air Ambulance is when you see so much death and so much bereavement – it does impact how you see the world. That is what worries me about the frontline staff at the moment – you’re so under the cosh and seeing such high levels of trauma and death, that it impacts your own family life.”

I have seen the two of them many times – as we all have. Their prominence in our lives makes them paradoxically difficult to comprehend. But I’ve never looked at them like I’m looking at them now.

The Duchess of Cambridge adds: “Mental health is so important. For people in the front line it’s needed more than ever. Often you forget to take care and look after yourself.”

To be seen and not to be looked at; to be considered morning, noon and night but never to be understood: this so far has been the fate of this couple.

For this cover story, Finito World engaged extensively with the mental health community. We spoke to those who have known the couple, to those who have worked with them, and – most importantly – those who have been involved in working on their central passion: mental health. Kensington Palace has also been extremely helpful with this piece, verifying facts where we had our doubts, and providing us with vital information which has helped us immeasurably. We would like to take this opportunity to thank them.

What emerges is, like all stories about the Royal Family, as much a tale about our collective identity as it is the story of these two people who everybody is meant to have some kind of opinion about.

On 23rd July 2020, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge announced that the Royal Foundation would give £1.8 million to various mental health charities as part of its Covid relief fund. The ten named organisations were: Mind, Hospice UK, the Ambulance Staff Charity, Campaign Against Living Miserably, Best Beginnings, The Anna Freud Centre, Place2Be, Shout 85258, The Mix, and YoungMinds. Finito World approached each for comment for this article, and received a range of replies which inform this piece.

In order to understand what is being achieved now, it is worth going back to the formation of the Heads Together campaign which was embarked upon at a time when Harry and William were still working closely together.

The Line of Duty

One former member of the Royal Household recalls that it was a ‘small tight-knit household’ which formed the original decision to focus on mental health. Led by Miguel Head, the then private secretary to the Duke of Cambridge, who is now a senior partner at communications advisory firm Milltown Partners, the household reportedly worked in a “highly collaborative” fashion. At that time, before the advent of Meghan Markle, the private secretary to the Duchess of Cambridge Rebecca Deacon (now Rebecca Priestley) and the private secretary to Prince Harry, Ed Lane Fox worked as a quartet, alongside the then Head of Communications Jason Knauf.

Another former member of the household recalls the sense of necessity which permeated Kensington Palace at that time. “The Royal Foundation was set up really with the wedding funds, the booty and the gifts which had come out of the wedding. What’s interesting is you have to do something with it and we kicked ideas around. There was a sense of ‘We’ve got this charitable vehicle – now what do we do with it?’”

The inner circle cast around for examples, and turned to William’s father for inspiration. “Everyone was saying: “The man on the street knows what Clarence House stands for. It’s the environment basically, and sheep farming. But what do we stand for?”

The answer came piecemeal but, once arrived at, would prove remarkably durable. “The first tranche was on wildlife conservation, and another was to do with sport and the community. And Harry had his inner city kids up in Nottingham. But it was a bit tentative – everybody was looking around for a good idea.”

The Wedding Fund was administered by The Royal Foundation and distributed grants to a number of charities. These were selected by The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge.

The first major grants awarded by The Royal Foundation were to ARK (an education initiative) and Fields in Trust (protecting green spaces for young people to play). The first major initiatives of The Royal Foundation of The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge and Prince Harry were Coach Core – (2012) launched at the time of the Olympics, Endeavour Fund (2011) and United for Wildlife (2013).

It was mental health which ended up joining up the dots. Another former member of the Household remembers: “Mental health was bubbling in the arena at that time. But I think it was William’s work with the air ambulances which made the crucial difference. It chimed also with Harry’s work with Invictus.”

Important insight came from the private secretaries. “It was Miguel Head who said, ‘Yes, we’ve got these communities like wounded servicemen who have mental health issues, but actually there’s a broader message here.’ One statistic I remember being trotted out was that the biggest cause of death in men under 30 was suicide.” It chimed with everyone: with William and Harry because of their experiences in the military, and with Miguel – or “Mig” as he was known – and Jason Knauf who also took a keen interest in the issue.

But whatever the contribution of the staff, all are agreed that the Duchess of Cambridge played a critical role. The issue chimed with her. “She soon got to know those issues, with things like post-natal depression – all that side of it she could relate to – and her morning sickness too.”

In fact, it was The Duchess of Cambridge who proposed mental health as the common thread that united all their work. The Duchess had previously worked extensively on mental health through her work with patronages Place2Be, The Art Room, Anna Freud Centre, and in her work with Action on Addiction’s MPACT Programme.

A naturally empathic individual, it was the Duchess who recognised the common theme running between each of Their Royal Highnesses’ work. She seized the initiative and today is rightly credited by all the principals as a vital driver of a campaign which has had remarkable success.

At the launch of Heads Together, William would give his wife appropriate credit: “It was Catherine who first realised that all three of us were working on mental health in our individual areas of focus. She had seen that at the core of adult issues like addiction and family breakdown, unresolved childhood mental health issues were often part of the problem.”

Of course, contingency also played its part. When the opportunity presented itself through The Royal Foundation of being charity of the year for the London Marathon, it was time to act. Their Royal Highnesses instructed their Private Secretary Team to work on mental health. A campaign had been born.

Cause Célèbre

This time the room is non-descript and the pair seem to be staring down from an odd angle. They’re more casually dressed – Kate in a zebra-striped top, and William in a turquoise sweater and blue shirt.

William says in relation to the pandemic: “A lot of people won’t have thought about their mental health – maybe ever before. Suddenly this environment we’re in catches up quick. The most important thing is talking – it’s been underestimated how much that can do.”

It is the day of the pledge on mental health and it’s notable that one of the least palatial rooms in the palace has been chosen. With William, whenever he talks of trauma it is with real authenticity. We all know what he has suffered.

He continues: “Trauma comes in all shapes and forms and we can never know or be prepared for when it’s going to happen to us. People will be angry, confused and scared and those are all normal feelings, and unfortunately all part of the grieving process.”

When Kate is asked about how she handles childcare there is also an air of authenticity about her: “You don’t want to scare them or make it too overwhelming. I think it is appropriate to acknowledge it in simple and age-appropriate ways.”

Of course, the way in which we hear these straightforward remarks has been altered by media coverage, with some sections of the media taking a perverse pleasure in trying to twist their lives into a tale with greater jeopardy in it than it can likely bear.

That’s not to say everybody is completely sold on mental health – and some of those we spoke with raised legitimate questions around royal involvement in charitable causes. When I speak to Lord Stevenson, one of the leading thinkers in this area, who submitted the Thriving at Work report alongside Mind CEO Paul Farmer to May administration, he initially laughs that he doesn’t like to get too involved in anything the royals are doing, feeling that it is a case of “good intentions.” He continues: “I remember Prince Harry giving money to charities involved with the army. Presumably it was based on the presumption that serving soldiers have worse than average mental health. Curiously enough, the evidence is that they don’t.”

And yet these misgivings are expressed lightly, and with a certain humour: they are not intended to cut very deep. They are instead a cheerful warning which might be levelled at anyone thinking about wading in to this area without deep understanding. Stevenson also explains in his exclusive essay in this issue that the area has benefited from some “strong royal patronage”.

Meanwhile, the journalist Toby Young argues that the mental health crisis is ‘complete balls’ but will not say more than that because he considers it “a good stick with which to beat governments over lockdown”. But another lockdown sceptic, Emily Hill, who writes regularly for the Mail and whose novel Love and Late Capitalism publishes next year, says: “I can’t quite believe that Toby Young – of all people – thinks there is no mental health crisis due to Covid and lockdown. People are still so terrified they are wandering about in the open air wearing facemasks as if the virus exists in the air. If that isn’t evidence of a mental health crisis I don’t know what is.”

This shows that the couple has found a cause which resonates across every section of society. They have been successful in alighting on the cause célèbre of our time.

The Inner Circle

So what has been the reaction? It’s remarkable how popular and durable the campaign has already proven, and across the political spectrum. Paul Farmer, the CEO of Mind, and co-author with Stevenson of ‘Thriving at Work’ tells us that “The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge do an incredible amount of charity work, raising awareness for important social and health issues, and we are delighted that they have chosen mental health as an area to which to lend their considerable profile.”

Victoria Hornby, the founder of Mental Health Innovations which powers Shout 85258 told us: “The support we have received from the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge has been phenomenal. Not only are they both passionate advocates for mental health, their continued dedication to Shout has helped to raise awareness of the service as a vital lifeline for anyone in the UK who is struggling to cope.”

Tom Madders, Director of Communications at YoungMinds wrote to us: “As a children and young people’s mental health charity, it is really important for their voices to be heard and the Duke and Duchess have spent time with us as a charity to really understand the issues that young people and their families face. Stigma around mental health can prevent young people from getting support or recognising when they are struggling. The profile of the Duke and Duchess means we can reach more young people and parents and make a real difference.”

Alistair Campbell and Fiona Millar meanwhile, who worked on Heads Together, tell us: “The younger royals’ focus on mental health is a good thing. We were involved in Heads Together and know, from the reaction that we got, that it gave people a lot of confidence to speak out about their own mental health issues when they hear others in the public eye (royal or not) doing likewise. Mental health issues can touch people from all backgrounds.”

Millar continues: “I particularly respect the Duchess of Cambridge’s work on the early years as the impact early childhood has on later mental health is too often overlooked. I believe she got criticised by some for getting involved in an area where there is already a lot of expertise, but if she can raise the profile of that vital phase, then we should only be pleased.”

Finally, there are those who have been in government who praise the royal commitment. Baroness Nicky Morgan, who has served as both Education and Culture Secretary, and now chairs the mental health charity The Wellbeing Café Project in Loughborough, tells us: “Their patronage, particularly of an issue like mental health which we really didn’t hear anyone talking about just a few years ago, is a real game changer and very welcome.”

Marlborough Light

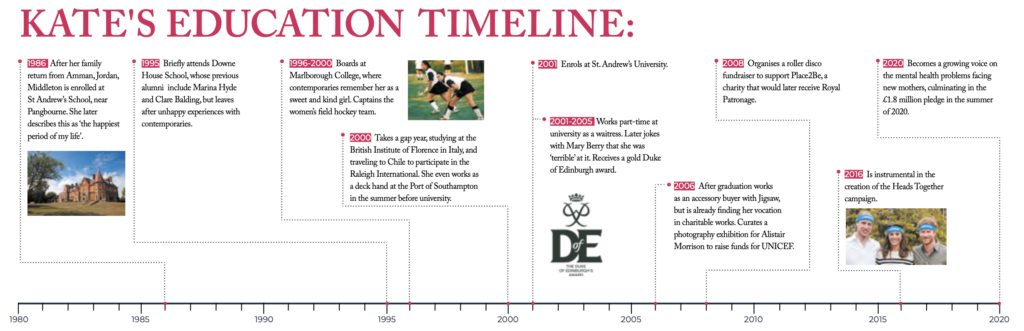

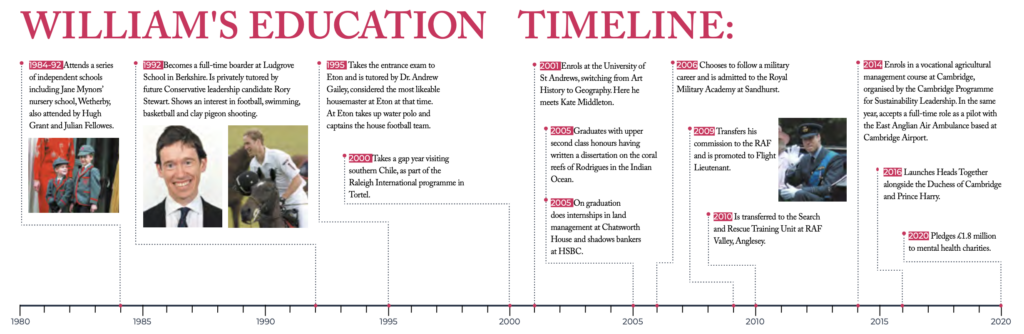

Of course, in another sense, the campaign dates further back to the creation of two highly empathic individuals who might choose mental health as their chief charitable cause. The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge are the same as the rest of us: they cannot be separated from their past, which means that their story is impossible to divorce from their education.

This isn’t just the case because they met in an educational setting, but because both individuals were shaped in similar educational environments – William at Eton College and Catherine at Marlborough College.

There is, of course, a marked difference in their two educations. At Marlborough, which Kate Middleton attended in the mid-1990s, nobody who knew her then particularly thought to notice her, for the obvious reason that nobody imagined they were going to school with the future Duchess of Cambridge. Whereas from birth, William has never known anonymity – and he will not know it. As Miguel Head told The Harvard Gazette in 2019: “The princes took the view that they were going to be in the public eye from the moment they were born to the moment they died and with that level of interest in them, the only way of coping with that would be to detach themselves from much of what is said about them.”

But among the old Marlburians we spoke to for this piece, some found it hard to remember Kate at all – and you get the sense that they’d been racking their brains ever since. Those who did, remembered a kind and unshowy girl, who fitted what Marlborough was turning into more than what it had been.

Oliver Osgood, 41, now an entrepreneur, explains that when Kate Middleton attended the place it was in transition: “At that time, the school had moved away from its spiritual philosophy of fun, freedom of expression and individuality. It had begun its shift from a sex, drugs and rock-and-roll approach in the 1970s to a ‘we’ve-got-to-get-great-grades approach’.”

Rosemary Cochrane, 40, who is now successful in healthcare recruitment at Oyster Partnership, feels that the shift took a little longer to come about: “There was nothing about mental health in those days. It was still a very druggy school, and wasn’t particularly academic. It was about building an all-rounder.” And how did Middleton fit into this? “She was definitely in the sporty gang. She was perfectly nice, and pretty – as was her sister, Pippa, and it makes them perfect for what they do today. She was just a very nice girl who played lacrosse, and who you didn’t come across at nightclubs. She was very lovely. She was never going to be loud and never put herself out there too much and would never be too in your face, or too loud – and never drunk. She’s not outspoken; she just does everything subtly.”

Sport remains an important aspect of the couple’s bond. Middleton was well-known for her athleticism. One former colleague recalls long car journeys with William where football was the predominant topic of discussion. “It wouldn’t occur to him to ask if you’re interested in the topic; his background makes him assume you are.”

Interestingly, sport plays an important part in any vision of a mentally healthier society. Mental expert Dr. Paul Hokemeyer, the author of Fragile Power: Why Having Everything is Never Enough, explains its relevance: “Leisure is critically important to our emotional and physical well-being. This is especially important for people who live in the intense heat of the public spotlight. Leisure, and sports in particular, provides us with an opportunity to get out of ourselves and to connect with a community of other human beings around a common interest and goal. This is because mental illnesses thrive in isolation, but retreat when we find meaningful relationships with other people and our natural environment.”

What most strikes you about the reminiscences of Old Marlburians is that even those who had little natural affinity with her do not talk ill of her. One, who asks not to be named, says she attended parties with Kate but “never got to know her”. It is a note of unknowability which might be deemed, along with her kindness, the leitmotif of her life.

An instructive simplicity comes across. Later on, people would paint her and her family as ruthless for falling in love with William – but it feels significant that they never do when they knew her beforehand. If she ever had peculiar plans of a royal marriage in those days which meaner elements of the press would come to imagine, then she hid them very well at the time.

Eton Mess

Over at Eton, William had a similar experience. Eton, despite its apparent pre-eminence, is an ecosystem interlinked with the other great public schools – particularly Charterhouse, Harrow, Repton and Marlborough. We might say that when the couple met they would share a set of common assumptions.

The unanimous view of contemporaries is that the school changed fundamentally once William arrived. Xavier Ballester, a contemporary of William’s, who now works in angel investment, recalls the shift: “He had about 28 bodyguards on different rotations – but in spite of that, he was integrated. He would be in the classes but there would be guards standing outside. They were always checking the bins, checking for bombs, and all this kind of stuff.”

Mike Lebus, who now works with Ballester at the Angel Investment Network, agrees: “It sounds strange saying it now, considering that he was obviously going to be our future king, but we genuinely did just see him as one of our housemates – another guy to chat with, watch TV and play sports with.”

Ned Cazalet also recalls the shift in the school. “We had prayers one evening where the housemaster also reads notices out, and a kid had pulled out a water pistol while walking behind Prince William and almost got himself shot. And throughout the school at that time, there was police and CCTV. It was a big shift.”

But what kind of an effect did Eton have on William? “It had an effect on him – it had an effect on everyone,” Ballester says. “It gave him confidence. He was a protected kid – and to make your way there you have to develop some confidence no matter how protected you are.”

What most emerges from all this is that in environments against which young people are inclined to rebel, neither William nor Kate did. In William’s case, one might initially think that there’s no mystery as to why William didn’t do so; he felt he couldn’t. But of course the example of Prince Harry – and before him, the examples of Princess Diana, Princess Margaret and the Queen Mother – makes one realise that it is perfectly possible for people to possess a privileged position and develop character traits which might not fit the expected pattern.

Cazalet also perceptively notes how the experience of public school is often impacted by who your housemaster is. In this, William was particularly lucky. Cazalet recalls William’s mentor the author and historian Dr. Andrew Gailey. “I remember he was quietly spoken. He seemed to have affection for his students. Some of the housemasters were chaotic, others were drunk, or tired or bored, or had some chip on their shoulder. But he was one of the best ones.”

Another old Etonian describes Gailey: “He was an excellent housemaster, a wonderful man and someone who I will respect for the rest of my life. He ran the house with a fine balance of responsibility and accountability that allowed us boys to thrive. He gave us enough of a leash to develop ‘autonomy’ but if this was teetering out of control he was excellent at recognising this and reining in. He was supportive and passionate. Andrew also taught me history at A-Level, but it is the way he led us in Manor House that I will forever be grateful for. I am sure my experiences of Eton would have been very different had I been in another house.” William couldn’t have found a better mentor.

Today Marlborough College has become focused on mental health. There is a tab labelled ‘Pastoral’ on its website with a ‘mental health and well-being’ sub-heading in the dropdown. In this the text reads: “We…believe that the skills which young people learn in adolescence, in terms of sustaining good mental health AND in terms of taking appropriate action when things go wrong, are skills which can be taken forward into university and well beyond, into adult life.”

One notes the capitalised ‘and’ which perhaps conveys a certain desperation to be on the right side of an issue which nowadays – and partly due to the most famous Old Marlburian – you can’t afford to be on the wrong side of. In a sense the school today has been Middletonised.

One former pupil, who was asked to leave due to a drink and drugs problem, told us: “I definitely think if my case came round today they would have got me counselling, and sought to look at why I was behaving as I was, rather than punishing me.”

Similarly, many of the old Etonians we spoke with continue to be shadowed by the bullying they saw, or experienced. One Etonian recalls: “You are in a very class-obsessed place where you have to tread carefully to not be exposed as a pleb and then derided for it. I was lucky in that I got a small scholarship and was in the top sets with others who had money off their fees too. I was also good at sport which helped a lot but some people were sent to Eton and got mercilessly tormented (a northern guy in my year springs to mind).”

Cazalet gets to the heart of the chilliness of the place: “Years later, when I decided to leave university early, my father said: ‘I hope you didn’t do anything to reflect badly on Eton’.” Another bemoans the presence of “casual, classist bullying” – although, all added that they were talking about the Eton of William’s time and that things might be better today.

We can see how sensitive young people like the future Duke and Duchess of Cambridge wouldn’t forget what was lacking in their schooling – even if that schooling was the best that money could buy at that time.

Dog Days

On Catherine’s side, there are other possible areas of motivation. The Middleton family, though it has sometimes been unfairly portrayed as grasping, has a strong compassionate streak.

Emily Prescott has interviewed Kate’s brother James Middleton about his work as a mental health advocate and feels that having a brother with depression may be a source of Kate’s inspiration in tackling the issue. “It was very moving to talk to him,” she recalls. “I can imagine that having that passion for dogs [Middleton is an ambassador for the charity Pets as Therapy] across the family dinner table must have had an impact on her outlook.” Prescott remembers discussing a famous quote by Milan Kundera during their conversation: “Dogs are our link to Paradise. They don’t know evil or jealousy or discontent. To sit with a dog on a hillside on a glorious afternoon is to be back in Eden, where doing nothing was not boring – it was peace.” Prescott adds: “He sounded almost in tears as he spoke about his dogs. He was a very sensitive person. Once I told him I wasn’t asking about Kate he seemed relieved.”

This sensitivity is also to be found in the Windsor family. One former member of the household who worked closely with William for many years, when asked what makes the royals special, tells us: “You’ll see the Duke and Duchess at a function, let’s say for families of those who have fallen in Afghanistan or Iraq. You can see them do the line-up, or circle the room, and you know that each person will have only 45 seconds with them as it’s a crowded gathering. And you’ll know that they all need something from that encounter. What’s amazing is that they always get that something. Everybody comes away feeling better, and lighter somehow. It’s a gift, and I think William and Harry both have it from Diana.”

We have to remember that Diana was there at the beginning of William’s schooling – but tragically, not at its end. Lebus recalls: “I remember his first day at school when he moved into the house. My sister and I passed his mother on the staircase while she was carrying a plant up to his bedroom, and it was surprisingly (but refreshingly) normal. We just smiled at each other and said “Hi”, as you would with anyone else’s mum and dad.” It is a touching image, especially in light of what would happen subsequently.

Hungry Gaze

Two media appearances by Kate Middleton. In one she is standing on stage, and launching the Heads Together campaign. “We know mental health is an issue for us all, children and parents, young and old, men and women of all backgrounds and all circumstances. What we’ve seen first hand is that the simple fact of having a conversation – that breaking the silence – can make a real difference. But starting a conversation is just that, it’s a start.”

Starting a conversation. That is a difficult thing to do when everybody is gawping at you. In a famous – and much-misread – article, which also contained some discussion of Kate Middleton’s predicament – the novelist Hillary Mantel recalls seeing Queen Elizabeth at a function at Buckingham Palace: “…the queen passed close to me and I stared at her. I am ashamed now to say it but I passed my eyes over her as a cannibal views his dinner, my gaze sharp enough to pick the meat off her bones…and such was the hard power of my stare that Her Majesty turned and looked back at me…”

And how does Elizabeth look when she turns back to Mantel? Does she look regal? Does she look different to how we would look if we were being stared at? No, she looks human, or as Mantel says, “as if she had been jabbed in the shoulder; and for a split second her face expressed not anger but hurt bewilderment. She looked young: for a moment she had turned back from a figurehead into the young woman she was, before monarchy froze her and made her a thing, a thing which only had meaning when it was exposed, a thing that existed only to be looked at. And I felt sorry then. I wanted to apologise. I wanted to say: it’s nothing personal, it’s monarchy I’m staring at.”

It is a novelist’s insight – that the paraphernalia of monarchy may in the end, whatever the tenor of our national discourse, amount to far less than we might imagine. And the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge are in the same predicament.

After that speech by the Duchess, there was some criticism that she had mumbled – and yet on the YouTube video she speaks perfectly clearly. Whatever she says or does, there will be criticism from some quarter or other.

Miguel Head continued to the Harvard Law Review: “It was actually quite liberating, because it meant that we as a team could concentrate on what we wanted to say about them. In essence, what we were trying to do was focus the interest in them on particular aspects of their public life, of their work in their early 20s as they were beginning to find their feet and experimenting with different topics, different careers.”

And yet it cannot only be liberating. This experience must also be suffocating. Furthermore, we cannot absolve ourselves from that since, as Mantel implies, it is us who are doing the suffocating.

The second appearance is on the podcast Happy Mum, Happy Baby, which aired in February 2020. The presenter Giovanna Fletcher says she is nervous after her introduction and the Duchess says: “Don’t worry -I’m nervous too.” For the listener, as for Fletcher, a gap is closed, a common humanity noted.

Later in the interview, the Duchess continues: “I had a very happy childhood, I was very lucky. I have a strong family. My parents were very dedicated. They’d come to every sports match and would be on the sidelines shouting.”

Some reminiscences ensue with Fletcher about her own childhood visits to Curry’s, and Kate interposes with a kind of agile empathy, “How about you? What was your childhood like?” This leads to a brief discussion of the bullying Fletcher experienced as a child. It is a very simple thing, you might think, when you’re being interviewed to mind at all about the life of your interviewer. Except to say that, in the experience of this interviewer, very few do – and many of them have far less profile than Catherine does.

Whenever you speak to anyone who knew Kate or William growing up the tone is different. It is matter-of-fact – above all, it is sane. The respondent almost seems to pity you for wanting to know – because if you have known them, there is no mystery. But for those who haven’t known them, there is the mystery of our looking so much to so little purpose. What we are peering at is our own frustration. Like Mantel at Buckingham Palace, we are somehow unable to accept that we are looking on human material, and that the answers to all the questions we might have about the couple do not lie outside us; they’re within, in our very need to know.

And the couple’s mental health campaigns seem to open up onto the idea that we could all do with a dose of sanity in our own lives, not just in relation to what we’re dealing with, our own strains and stresses – but in relation to them.

A Scotland Romance

This sense is brought home for me when I begin to look at the couple’s time at St Andrew’s University. I speak with Stephanie Jones, now a successful brand manager, who attended St Andrew’s at the same time as William and Kate – and in taking art history, did the same course as both, though William subsequently changed to geography.

“It was all discreetly done,” Jones recalls. “I remember walking down the street and tripping and then looking up and seeing Prince William quite near and thinking that this wasn’t the impression I wanted to make! But he had no bodyguards around him. I remember seeing him in the pub too and if he had a security detail it was entirely made up of hopeful girls!”

Of course, this isn’t the whole truth. If things seemed normal to contemporaries, they sometimes seemed to be spinning out of control. Around this time, once the relationship broke, Middleton became ‘Waity Katie’ in the media – a horrible moniker. And of course, there is nothing to make you think about the question of mental health quite like running into the reality of the tabloid press.

It is as if St Andrew’s, in its size and remoter location, were better able to accommodate William’s arrival than Eton had been. Jones says that the principal change she remembers with William’s arrival at St Andrew’s was that the year William joined, there was a marked increase of blonde American girls: “But whenever I saw him, he seemed normal. We all felt this responsibility to sort of let him get on with it, and enjoy the university and not feel hounded.” Once again, we near the suspicion that William may not only be projecting normality – that he may actually be “normal”.

The Diana Effect

But of course, there is one area in which William isn’t normal and this is in the terrible fate that his mother met on 31st August 1997 in the Paris car accident.

Jones continues: “We were protective about what happened with Diana. I would walk past charity shops and see books about her in the window and think how tacky that was and how hard it must have been to walk past if you were William. His pain was being commercialised.”

This is empathetic – and today, we still feel it. An observer of the palace who has known William for years says that it infuses coverage surrounding the boys. “They’ll always on some level be the boys traipsing behind the coffin.”

So grief enters the story – a wound so painful that we almost think it might be an impropriety to discuss it. But Dr. Paul Hokemeyer argues that we cannot avoid it when discussing William and Kate’s mental health campaigns. “Prince William is a brilliant example of the healing power of two key psychological traits known as resilience and grit,” he explains. “The first, resilience, refers to our capacity to make meaning out of tragic events and to move ourselves and the world around us in a repairative direction after the event.”

This feels relevant as it is something like this “repairative direction” in which William now seeks to steer us all with his mental health campaigns.

And the second trait? Hokemeyer is clear: “Grit enables us to tolerate short term discomfort to attain a long term goal. As this relates to Prince William, he had to sit not just with the crushing pain of losing his mother, but with also being an obsession of the public; and he had to do this without devolving into a tragedy himself. His capacity to do this with dignity and grace is exceptional. Not only has he navigated that terrain brilliantly, he’s gone on to create a family that reflects the class, dignity and nobility of decades of British royalty.

Hokemeyer continues: “The trauma of losing a mother at an early age sets a child up for a journey down the path of meaning and repair (resilience and grit) or of wandering through the brambles of life, lost and emotionally alone. The individuals who travel on the first path have what is known as a robust ‘internal locus of control’. They’ve internalized a healthy sense of self. As this relates to picking a life partner, people with a healthy internal locus of control pick mates who compliment them in their journey of healing and providing hope to the world around them.”

Another psychologist, Dr. Jonathan Garabette, a private consultant psychiatrist who also specialises in mental health, is less sure about the whole question: “Our choice of partner is a complex and enigmatic area. I think it’s important to consider that we are living in the internal world just as much as (or even more than) we are living in the external world and our internal worlds are populated by memories, relationships, people, infantile childhood, adolescent and different parts of us and all of this exerts a much greater effect on our psychology and our choices than we may consciously be aware of.”

And how may that have affected William? “Many people, especially after being affected by trauma, are searching for a relationship that provides meaning, and a sense of safety and connectedness and we will each find this in different ways in different aspects of others. It’s also important to remember that what we see on the surface, particularly on public figures, is just that – it’s a surface impression and we should remind ourselves that they and their partners are complex three dimensional human beings and the connection that people may have between them may not be easily apparent to those on the outside.”

So is there anything we can say about the choice of life partner someone might make who has been through trauma? “When I speak to people, especially those who have been traumatised, about how they came to end up with their partner, it’s often because that person has managed to touch upon a very deep and intimate part of that person that others might not even have had the opportunity to be aware of.”

Trauma and grief make William an immensely plausible campaigner for mental health. It is possible to imagine him in his current role without the awful loss of his mother, but hard to imagine him being so effective in it. Garabette’s remarks sensibly distance us from William and Kate, and indeed they remind us of the essentially unknowable nature of other people.

This fact, so simple and non-negotiable, is something about which contemporary commentators of the couple seem in denial: a typical Mail or Tatler article today is full of a bogus desire for an insider’s light bulb moment which will suddenly open everything up – hand them to us on a platter. This cannot happen; and shouldn’t happen.

But Garabette also reminds us that their internal worlds are similar to ours and that if we really want to know what they think, we need to know what we think. It isn’t too much to suppose that this is one aspect of the conversation the couple wants to start with their campaigns. Again we return to the notion that a really wide-ranging national conversation surrounding mental health would also necessitate a fundamental restart of our relationship with them.

Action Figures

But as the couple has pointed out, it isn’t just a conversation that needs to start; action has been pledged. The £1.8 million which the couple pledged to charities is already making a tangible difference to some of the charities under discussion. In the box opposite we highlight some of the work that has already been done with the money pledged by the Royal Foundation.

But how does the allocation of funds work in practice? One former colleague, who attended numerous meetings at the beginning of the process, explained the ethos surrounding the mental health campaign: “The Duke and Duchess are very private necessarily, but absolutely committed and passionate about their work. Their initiatives take a long time to evolve as they don’t want to put their name to anything that will fizzle out. It has to be long-term and sustainable across a large swathe of society, so they can get their teeth into it.”

This feels, then, like a new approach to royal patronage? “It is a bit of a departure,” the former household member continues. “Look at the Queen. She has 900 patronages, and it used to be that as long as you weren’t doing anything stupid you’d get a patronage. Now they’re careful about what they want to get behind: it’s there with you for life, and they’re very keen to make sure their causes are followed through on.”

So what happened? It’s important to note that in giving the monies, the Duke and Duchess haven’t become patrons of those charities. The £1.8 million was granted by the Royal Foundation through a bespoke fund set up as part of the organisation’s response to COVID-19: it included, but was not limited to, support for Heads Together partners. Decisions on allocation of funds was taken by The Royal Foundation, whose current CEO is Jason Knauf, in line with expectations of Their Royal Highnesses, donors and trustees.

The impression then is that this was a team effort, with Their Royal Highnesses demonstrating real leadership. Others Finito World spoke with also praised the wisdom of private secretaries past and present and the role of trusted people in the sector, such as Paul Farmer, now CEO of Mind, and Victoria Hornby, who runs Mental Health Innovations.

It has been an extremely fruitful and productive relationship: Hornby would be instrumental in establishing Shout 85258 in 2017 with the Royal Foundation’s largest ever grant of £3 million. Meanwhile Mental Health at Work was established in partnership with MIND. Other projects also came to fruition, most notably Mentally Health Schools in concert with The Anna Freud Centre, Place2Be and Young Minds. This is no casual dabbling in the sector, but a profound engagement with a societal problem.

All those we spoke with emphasised the personal commitment of the principals. Hornby explains that the Duke “went above and beyond when he became a Shout Volunteer. After undertaking rigorous training, he joined our army of 2,800 volunteers who provide anonymous, in the moment, mental health support to people in urgent need of support. Our volunteers were absolutely thrilled when Prince William revealed, via a video call, that he was on the Shout platform with them.”

Farmer also spoke to Finito World extensively for this piece. We asked him what impact the Duke and Duchess’ campaigns had had: “Heads Together has sparked millions of important conversations about mental health” – again the importance of starting conversations – “and the Royal Foundation has raised money to support innovative projects to tackle the challenges we can all face in talking about, and seeking support for, our mental health in the workplace,” he explains.

But Farmer also highlights areas for improvement. In particular, he argues that the country needs to think fundamentally about the nature of the workplace: “All employers – including government – should be reflecting on how work can be undertaken moving forwards. Within many workplaces, the sources of poor mental health at work are often cited as including unrealistic demands, excessive workloads and problematic relationships with colleagues and other stakeholders.”

And how has the pandemic altered these causes of stress? “They were prevalent even before the pandemic, but research suggests mental health among staff has worsened further. Data from 40,000 staff working across 114 organisations taking part in Mind’s Workplace Wellbeing Index (2020/21) found two in five (41 per cent) employees said their mental health worsened during the pandemic.”

Farmer is also disappointed that, after the Theresa May administration welcomed the Thriving at Work report, its recommendations haven’t been properly implemented by the Johnson administration: “They have failed to improve protections from discrimination in the workplace in the Equality Act 2010 for people with mental health problems. Although they consulted on making improvements to Statutory Sick Pay (SSP), including phased returns to work and expanding SSP to the lowest paid workers, last month the UK Government announced they would be making no changes to SSP.”

When we asked Farmer to describe the effect of this recalcitrance, he was blunt: “As a result, many people with mental health problems have been left without access to the protections they need, and risk being pushed out of the workplace. We believe that the UK Government can and should do more – in the case of SSP, this is a recommendation that four years on, has still not been actioned.”

A spokesperson for the Department for Work and Pensions said: “The pandemic was not the right time to introduce changes to the rate of Statutory Sick Pay (SSP) or its eligibility criteria. This would have placed an immediate and direct cost on employers at a time where most were struggling and could have put more jobs at risk. We instead prioritised changes to the wider welfare system which is the most efficient way of providing immediate financial support.”

The spokesperson added: “As part of our £500 million mental health recovery action plan we are also helping people with a variety of mental health conditions, including though the expansion of integrated primary and secondary care for adults with severe mental illness.”

Asked for positives, Farmer had this to say: “We’ve now seen over 1250 organisations – including most Government departments – sign the Mental Health at Work Commitment, demonstrating their commitment to better protecting, supporting and promoting the mental health of their employees.” This is a tangible achievement and shows the impact of which Kensington Palace is capable.

But the failures of the Johnson administration on this front open up onto the thorny question of Kensington Palace and its relationship to government.

Nicky Morgan, a former member of Finito’s advisory board, who has deep experience of government, explains how she never worked with the Royals while in office – and this turns out to be the norm, even among senior experienced politicians. Asked what government could do to help on mental health, Morgan said: “As the founder and now Chair of Trustees at a small mental health charity and social enterprise in Loughborough, I can say that keeping on top of all the paperwork is quite a task and we have really had to make sure it doesn’t distract us from the mental health support work we do and the activities we provide.”

The Turning of the Key

So is there a role for government in this area? “I definitely think it should be left to local communities and groups to identify where charitable support is needed and that this shouldn’t be coordinated by government,” Morgan continues. “The one area government could help is in encouraging the NHS to work in a more systemic way with local charities: too often at the moment it is purely down to whether local individuals happen to meet and can build good working relationships.”

Fiona Millar adds: “From my own time working in government, and subsequently as an activist, I would say that focussing on one specific issue and becoming “expert” in that issue is much more effective than dipping in and out of different causes.”

There is food for thought here. Dennis Stevenson tells me that ‘mental health doesn’t really need government at all anymore”. On the other hand, the likes of Farmer are clear that there is more to do.

The likelihood is that Kensington Palace will continue to work its own terrain. One former member of the Royal Household, who worked for the couple around the time of the London Olympics, recalls: “We might work with government a bit on the sport side of things, and have Hugh Robertson (the then Minister for Sport) to the Palace. But, in general, for big projects, if we wanted guidance on the NHS, say, in relation to mental health, we wouldn’t go to the Health Secretary but to the NHS itself. In general they prefer to keep politics out of it.”

Another source agrees with this and adds that this attitude is to do with “wariness about how the Prince of Wales was drawn over the coals for black spiders and so forth. Kensington Palace now wants to make it clear that what it’s doing is completely apolitical.” The source adds: “The role the Palace really plays is the power of convening. Everybody will take a meeting, and so they can get different people together in the room.” With their mental health campaigns, that’s exactly what the couple has done.

Band of Brothers

Government turns out not to be a thorny issue at all compared to two things which have turned out to be particularly headachey. The first is Harry, and the second is the press. But the more you look at that problem, the more they come to seem one and the same thing.

In the first instance, I speak to Nicky Philipps, the brilliant society portrait painter whose picture of William and Harry hangs in the National Portrait Gallery. Philipps recalls painting the commission with great fondness, although she admits that the picture was painted under considerable pressure. “It was very nerve-wracking – until I met them,” she tells me.

Again, the sense arises that these people we think about so much, turn out to be so much like ourselves up close. “Harry was so sweet. The person I knew is not the man in California whingeing about his setup. I don’t know what’s happened now. He was so lovely.”

Philipps explains some of the complexities of organising a royal portrait: “The light is all wrong at Clarence House,” she recalls. “I was determined to have proper north light, but the sun was pouring through and changing the colour and causing havoc so I asked if they could come to my house.”

And what was that like? “They organised it and the police came.” (Again, the police: harbingers of the royal presence). But when the principals arrived, everything changed. “They were just like everybody, very natural and fun together and they created their own pose. I didn’t have much to do – they arranged themselves.”

Today Philipps, who has also painted the Queen on three occasions, looks back on that 2008 sitting and says she’d have liked more time. “They were in uniform so I had to take photographs of the uniform and the medals and couldn’t get much down there. I had five sittings – which sounds a lot but it isn’t when you’ve got to do two heads.”

It’s worth looking at this painting closely. Over time, the picture has changed – one thinks of Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian of Gray, where a picture changes because the world around it cannot remain static. “What’s quite weirdly prophetic,” continues Philipps, “is that I couldn’t find a way to arrange them with William in a doorway and still have Harry to be looking at him. There’s this lintel going down the middle, and I have an awful feeling it’s slightly off centre. Now I look at it and it’s the Great Divide.”

If you look at the picture, it’s true – the two princes are looking at each other fondly, but they are also irrevocably separated, each inhabiting separate fields of energy, as they sadly do today in real life.

“Never in a million years would I have thought it would have ended like this,” Philipps continues. “Harry was more casual, and William was more on it – but they were one. They were lifelong friends so far as I was concerned.”

There seems little doubt that the press must bear some of the blame for the deterioration in their relationship. One person who used to work at Kensington Palace was worried at the time about the drip effect of negative stories about the princes: “They would definitely get hurt by what they read in the press about each other.”

Philipps has also painted the Duchess: “Kate’s absolutely sweet and extraordinarily graceful. I never met anyone who carries themselves so well and is so patient.”

Nicky Morgan is among those who understands the difficulty ranged against the couple when it comes to the media: “You have to learn to ignore much of the commentary directed at you, decide whose opinions really matter to you, and realise that social media is both a great way of communicating a message about your work but can also be a source of great abuse and distraction.”

Tattling Tales

None of this will be remotely news to William and Kate, who deal – and will deal forever – under a greater scrutiny than any Cabinet minister. But the dynamics are the same – and again they always work against narratives of simplicity and happiness, since it has been decided that such stories lack the ghoulish jeopardy which we apparently expect from our newspapers.

Once again, there is a simpler interpretation of their story. Philipps adds: “I think it’s been a fantastic revelation to see how a middle class family can be so cohesive. Although the Royal Family is a very solid block in a way, I think to be taken under their wing would be a lovely thing to experience.”

This brings us to the unpleasant story in Tatler which published earlier in the year under the headline ‘Catherine the Great’. This story, run under the editorship of the Duchess’ contemporary at St Andrew’s Richard Dennen is an example of the kind of journalism – full of insinuation and straightforward unkindness – which this publication opposes. Dennen appears to have befriended the Duchess of Cambridge while at St Andrew’s, and is remembered by Old Carthusians as a shy boy, whose subsequent transformation into a society gadfly has always caused considerable perplexity.

The story posits a Duchess who is tired of the stress, when her work ethic according to those we spoke with is impressive. Meanwhile Carole Middleton appears as a snob, when the reality is different. A source said: “Nobody reading that Tatler article who knows the family would recognise the description of Carole which it contains. In reality she is a straightforward decent person. In my experience successful business people do not have time to be snobbish – they’re too busy. And Carole is very successful and has been a great role model for the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge. There was never any need to spin any of this negatively.”

The Throne of Reason

What should the Royal family do in relation to the media? Michael Cole, who formerly worked for the BBC as royal correspondent, tells us unequivocally: “The British media are not the enemy of the Royal Family. As I have said to more than one royal personage, the time for the Royal Family to worry about the media is when the media is no longer interested in the Royal Family because that will mean the game is up because the Great British Public is no longer interested either.”

It will indeed be a sad day when a belief in good journalism departs Kensington Palace, although Miguel Head is among those who attests to Prince William’s belief in the enduring importance of the Fourth Estate when it is doing its job properly.

But Cole’s remarks also overlook the possibility that the onus may lie with us to look differently, as I suggested at the beginning of this article.

Covering William and Kate, one begins to sense that too often we overcomplicate life. Their story is simple just as their mental health campaigns are admirably straightforward. They were born into well-to-do families, and fell in love, and one of them was set to be the King of England – and in our system someone always will be monarch. In time, the pair found that if they were to do good it must come out of the gift each had, and which each had seen in the other: empathy.

And so it went. “Too often, people feel afraid to admit that they are struggling with their mental health,” the Duchess of Cambridge has said. “This fear of judgment stops people from getting the help they need, which can destroy families and end lives. Heads Together wants to help everyone feel much more comfortable with their everyday mental wellbeing, and to have the practical tools to support their friends and family.” It is a perfectly simple message, and we might call it bland – but equally we might call it true.

Perhaps in the last analysis, the couple’s mental health campaigns ask us to correct our attitudes to class and to celebrity. If we were to do away with our obsession with the trivial, we might find we suddenly have room for what really matters: the creation of meaningful lives where we don’t seek to tear one another down, but to look out for one another.