BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

By Paul Joyce

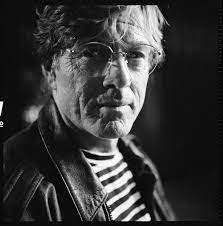

When people ask me as a photographer what my tip is, I say, “Follow and chase the light.” It’s a thing my old friend David Hockney told me: when the day is beginning to close and the sun is on the last buildings – go to those buildings. That’s what Van Gogh did. If you look at his early Dutch paintings, they’re dark interiors, and everything’s grim and brown. Then you get the wonderful Yellow Period, and it all changes.

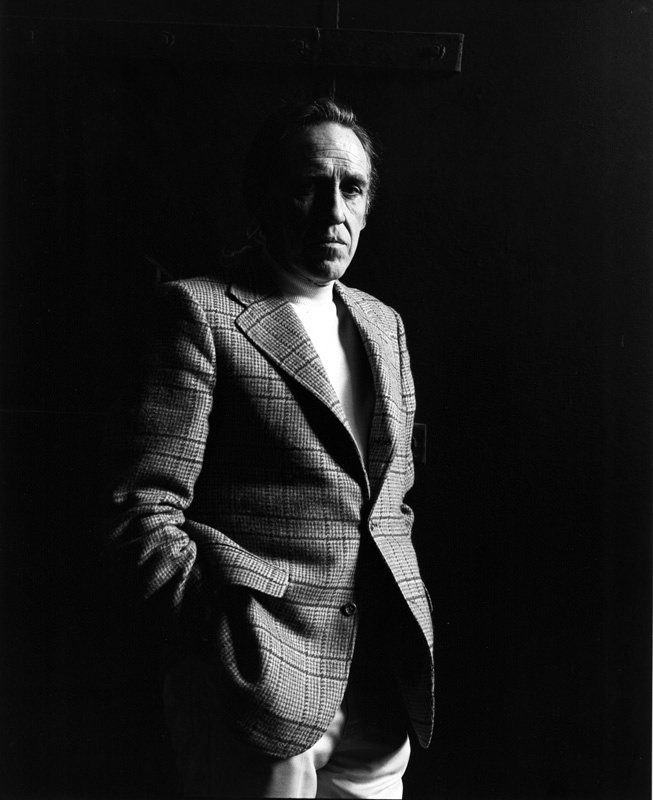

My subjects vary, but I’ve come to learn that celebrity has its dangers. I remember Elijah Moshinsky, who was a very fine theatre director, and who died of Covid recently, saying of Placido Domingo that he’s totally isolated from the world. Everything was done for him – he’s cut off. He never talked to ordinary people, or mixed with them.

I’ve always photographed my subjects out of an artistic need. The only commissioned portrait I did was for Condé Nast and was of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, the writer of Heat and Dust – a wonderful Indian lady. I took one of the worst portraits I ever took in my life and Condé Nast and I agreed it shouldn’t be published. Why was that? It was because I didn’t choose her. Even though I admired her, I couldn’t do anything with that face. You have to have the admiration for the work, and also a sense that the face is going to tell some kind of story.

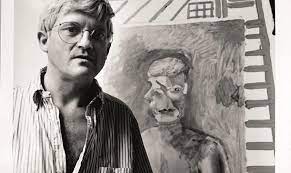

So I could never be David Bailey. I have a story of David Hockney being photographed by Bailey. Hockney was told to go to the studio and was waved in and shown his way to a white background. And David Hockney said: “Where do you want me?’ Bailey says: “Against the background.” David stands there. Bailey gives him a scarf and he says, “Make like a bat!’ And Hockney says, “What?” Bailey repeats: “Make like a bat!” And David waved his arms. Click, thank you – and that was it.

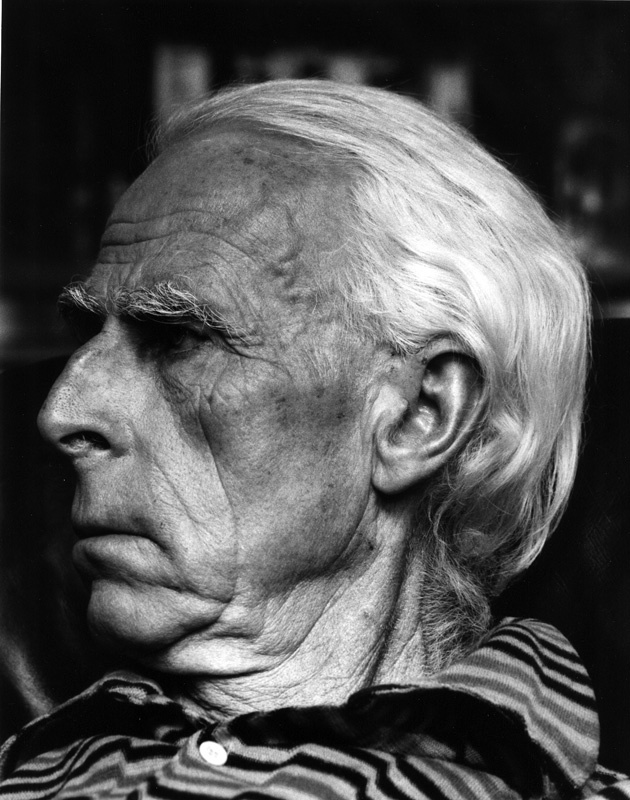

Samuel Beckett was wonderful. I’d tried various careers including banking and estate agency, and not got anywhere. This was before film schools. They were trying to establish a National Film School. Also there was a rogue organisation called the London School of Film Technique which occupied a building in Charlotte Street which subsequently was occupied by Channel Four. The Greater London Council began to give grants, and they’d send you some money to help make films. I sold my MG, my golf clubs, banked the cheque and made a film.

I’d seen the Royal Shakespeare Company used to do readings rather than full scale productions on a Sunday, and one was by Beckett called Act Without Words II, which was about 15-20 minutes long. I thought it was great, and I set my version on a rubbish dump. I didn’t have the rights to the film. I finished the film and didn’t know what to do. I showed it to Harold Pinter and Pat McGee, one of the great Beckett actors. The word got out to Sam I’d done this, and to John Calder, who was his publisher. They summoned me to Calder’s house.

I set up a screen and a projector, and I went to Beckett’s Harley Street apartment. I went up, and there in the corner was this figure with a Guinness: Sam. “Oh Sam, this is Mr. Joyce,” said Calder. I set up. Beckett pulls his chair up and sits about two feet from the screen meaning all you could see was his shadow. I started the film, and I was nervously waiting by the projector. I noticed that his shadow was shaking. I thought: “Oh God, he’s seething.” But I went closer and he was laughing – shaking with laughter.

At the end, he said: “What do you want to do with it?” Calder interjected: “You own it, Sam! This is where you negotiate.” Beckett said: “Well, Mr Joyce, what would you say to 50p?” I said: “Yes”. He said: “Would you like some Guinness?”

As a frustrated drama director, I turned to photography as a way of surviving. You’re treated suspiciously if you wear different hats. I miss theatre directing – I’d love to do Chekhov now.

I think back on the people I’ve photographed and it does seem unreal. Jane Fonda was wonderful. I was a callow youth on secondment to Paramount to do a documentary. I remember the Rolling Stones arrived, and looked like ruffians – that was an eye-opener.

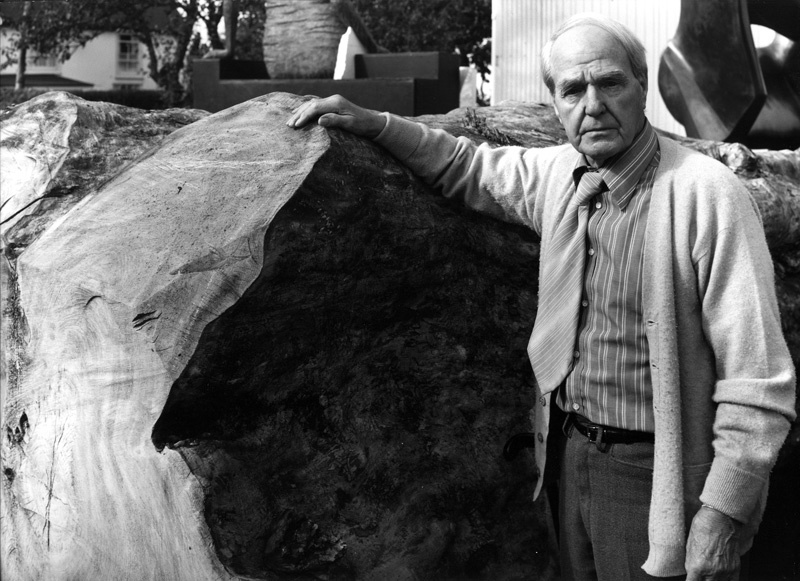

Henry Moore was a pretty tough, short Yorkshireman. He didn’t suffer fools. He also told me something I never knew: you can’t do decent sculptures in wood if the wood is from a tree that’s died. You have to have fresh, green wood and when I was there, there were huge lorries of wood delivered just for him. I don’t understand sculpture really. Either it’s realist or it’s not but I suppose you could say the same about painting.

Quentin Tarantino – we don’t keep in touch now, but I knew him earlier in his career, and he owns one of my paintings. I saw Reservoir Dogs before anyone else. He’s pretty sparky and very opinionated. Years ago, before Groundhog Day became a classic we agreed it was a classic. I think we disagree a bit about the value of such as Bollywood and horror!

As you get older you realise, we all have feet of clay. There was only one saint I met and that was Cesar Chavez. He represented Mexicans workers who were exploited in gathering the grape harvest. He campaigned long and hard. I met him through Kris Kristofferson who did concerts for Chavez’s cause. He was in danger constantly of assassination. He was disrupting this system of relying on cheap labour.

We have a need to deify and the need to imbue someone with the power of celebrity. It’s as if we will it on them so we can help them in some way. If they’re not powerful, what’s their use? With artists, they have a vision to transmit which is beyond what we have. It’s not saintliness, it’s not goodness, or grace or anything like that– it’s a vision, a way of looking at the world which changes our own way of looking at the world. Let that be enough.

I met Johnny Cash through Kris Kristofferson. I never met Dylan. I think he’s one of the great authentic geniuses. I had my doubts about the poetry – but the lyrics are finally amazing poetry.

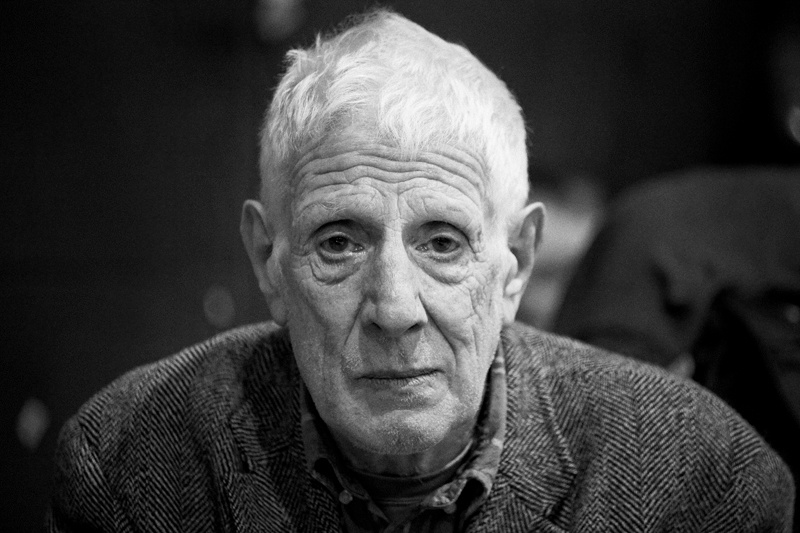

Spike Milligan I got to know – he was lovely, difficult and mad – as you can see in this photograph. He’d come to dinner and tell us stories about how during the Second World War, they’d paint on the bombs: “Good luck boys, up yours!”