BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

I meet Fatima Whitbread at a restaurant in Westminster and immediately warm to her kindly down-to-earth manner. Whitbread is one of our best-loved athletes, having won the World Championship in the women’s javelin in 1987, and a former world record-holder in that event.

We sit in a corner and order our food, which prompts reminiscences about Whitbread’s relationship to diet when she was a top athlete: “You are what you eat – for me, when I was a competing athlete I was constantly working three times a day training. Most of my competitors were six foot and I’m 5 foot 3 so my diet had to be right. I was on a diet of about 8,000 calories a day which is a huge amount, usually women are on 2,500-3000.”

But Whitbread’s story isn’t an ordinary one. Her childhood is enough to make you fight back tears. She was abandoned as a child and spent her early life in care. “I was left to die,” she recalls. “A neighbour heard a baby cry and called the police. They rammed the door down and rescued the baby. I spent the next seven months in hospital with malnutrition and nappy rash – I’m pleased to say I’ve recovered from that.”

Whitbread says this matter-of-factly and I find it hard to feel that there is residual trauma: she is serene, and I will come to learn that this has to do with the rare sense of mission she feels about fixing the social care system. “The reason it’s been my ministry is that I was made a Ward of Court by Hackney Borough Council. I spent the next 14 years of my life in children’s homes. These were institutions with large numbers, all run by matrons – and our emotional needs were not really being met.” Whitbread then gives me a heart-breaking detail: “My first five years were spent in Hertfordshire.

I spent a lot of time in the playing room which faced the car park. I remember whenever I saw anyone come in I’d say: ‘Is that my mummy coming?’ A lot of us children felt that way. Nobody ever really sat me down to discuss things. There was nothing at Christmases – nothing to indicate there was anybody out there for me.”

One day Whitbread’s mother did turn up, when the future World Champion was five years old, and this led to an unspeakable set of events. “That morning I sat in the foyer. There was an opaque glass window and the matron opened the door and a large lady with curly hair came in – but she never looked across to me or made eye contact. Then there was a lady with mousy hair, duffel coat on, smiling and engaging and I thought: ‘That must be my mummy’.”

But of course, her mother was the lady with the curly hair: “In all the journey down to the next home in Hertfordshire, I sat in the car and nobody spoke to me. The biological mother never spoke to me. We got to the next home, a small residential place, and I was told to go through to the garden. There was a little girl of four there, and I started playing with her. I was about to go down a slide, and then I felt a hand on me: “You look after your sister otherwise I will cut your throat.’ Those were the first words my biological mother said to me.”

Another appalling episode occurred when Whitbread, aged nine, was taken out of the home and raped “at knifepoint” by her mother’s then boyfriend. There seems to be no other word for this than evil. But incredibly, the story has a happy ending. “Sport was my saviour. I was at a netball match and I saw a javelin on the floor and it seemed interesting to me. Then a voice behind me said: ‘I see you looking at that javelin. Would you like me to teach you to throw it?’ This would turn out to be her surrogate mother. “Through that I discovered the love of the Whitbreads,” she recalls.

All this amounts to a damning indictment of the social care system as it was in the 1970s, but more worrying than that is that it isn’t necessarily leagues better today. In fact, it seems an issue which governments don’t want to go near. “In many respects it’s the same. I’ve seen governments come and go, and the care system really is broken. It’s not serving the children well.”

To say that Whitbread is a passionate campaigner is to riot in understatement: throughout our conversation I can sense the intensity with which she used to throw a javelin has been transferred to this admirable mission. She is also, of course, a loving advocate as she knows exactly what she’s talking about – precisely what it feels not to have your needs met as a child. Knowing the terror these children are experiencing, she knows the dimensions of love required to fill these gaps. “I’m a great believer that children are our future, and that what they become will define what our society will become.”

So what’s the goal of Fatima’s campaign? “I want to build happy lives, better communities, and a better society, and the only way we can do this is with collaborations,” she tells me. “I’ve confirmed a two day summit next year for the 23rd and 24th April at the Guildhall in London. We’re non-political but we do need cross-party support. We want to harness the power of one voice and bring the four nations together. There’s a lot of good work on the ground level but there’s no collaboration.”

The summit will include young people (‘they’re at the forefront of everything’), as well as decision-makers, charities and donors. What Whitbread is aiming at is nothing less than “the rejuvenation of the system” through strategic partnerships. “I want to bring the private sector in too,” she says with her bright, kindly eyes flashing.

“We’re looking at employability initiatives for our young people who are between 18 and 25 year olds to help upskill our young people. 27 per cent of our young people suffer from mental health problems too – and affordable housing is another issue which we need to tackle. The people in the system don’t have Mums, Dads, aunts and uncles to advise them and, appallingly, the government wipes its hands of it. In addition to all this, when they leave the system, 33 per cent of them in their first two years end up homeless.”

But the forces of darkness likely haven’t reckoned on the astonishing energy of Whitbread. “It’s down to me to use my lived experience and Olympic platform to meet people, to get through doors, and get the campaign together.”

Fatima’s UK campaign is seeking private funding in order to roll out an ambitious scheme across the country. For only £20 a week – which translates to £1000 a year – individuals or companies can sponsor a child in care to take part in weekly activities around technology, sport or art – according to what the individual’s interests are. “I want to make sure every child has the chance I had to become an Olympic champion.

I want to put them on a human path to reaching their potential and their goals. Every child has a right to a safe and happy childhood, but if they do end up in the care system, they need to have a safe, secure pathway to come out of that system, to be educated properly, and to feel secure that there’s a proper foundation for the future. In that way, they can break that cycle and live a proper independent life so that history won’t repeat itself when they have a family. I believe we can manage that: it’s not impossible – in fact it’s very doable.”

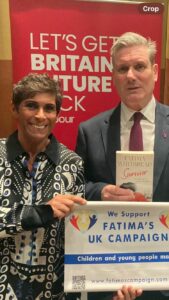

Others agree and have pledged their support – especially those in the new Starmer administration. “We have a charity dinner on the first night where Lord John Bird, the founder of The Big Issue will speak. Sir Keir Starmer has pledged his support as have members of his government such as has Yvette Cooper. The Timpson family do a lot of work in prisons and they are also on board.”

Prisons are very important to the campaign. “I do a lot prison visits,” Whitbread says. “I want to engage with young people so they have something to go to. That’s half the problem for young people when they come out: there’s nothing to come to. Then they realise they’ve got a warm cell, food and friends inside and it’s a wasted opportunity for life. We have these collaborators but who don’t talk to each other, which is a shame. We’re all in it together.”

Whitbread is one of those rare people who has found a second act in life – and she is pursuing it with the same passion that she did the first. There is a possibility that if we heed her call, we can all hand on a better life to the children of the future.

To learn more go to: fatimascampaign.com