BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

When we look at the famous or the successful, graciously hosting television cameras in their comfortable homes, it is easy to assume that they have found themselves inoculated from what Hamlet calls ‘the shocks and arrows of outrageous fortune’. There is the sense that all that is difficult or troubling has been brought to heel somehow.

One early example of this genre concerns the architect Frank Lloyd Wright approached in 1953 with the reverence with which someone in medieval England might approach a King by NBC Chicago’s Hugh Downs. This interview is in many respects a ridiculous affair. Wright is treated – and clearly regards himself – as not just a great artist but a seer and a sage.

He may well have been all those things, but he is also plainly a self-regarding one. Throughout the interview, he sits with a large book inexplicably on his lap, like some vast Bible, which the viewer is invited to assume must be a compendium of his drawings. His answers are philosophical and one can never be sure if he is definitely looking Downs in the eye – certainly the impression is that Downs has come to Parnassus to address a higher form of life.

Many will perhaps agree with Frank Lloyd Wright’s estimation of his own abilities while thinking he could have been more modest about them. Wright is one of those few architects who we can certainly say changed architecture, though it could sometimes be a bit tiresome to hear him point this fact out so often. It suggested perhaps that he had something to hide, and I think he did: his moral self, which was, biographers agree, by turns slippery, cunning, abusive, untrustworthy and arrogant.

This queasiness one feels about Wright is something we need to get out of the way before we discuss his genius, which is far more interesting and surprising than the news that well-known people often behave badly.

More interesting – and it is especially worth considering for anyone who happens to YouTube the NBC Chicago interview – is Wright’s vulnerability, arising out of a lifelong familiarity with tragedy. In fact, looked at closely, Wright’s career involved a regular collision with adverse circumstances – some of them fairly typical and at least one of them unthinkable, which we shall come to in a moment. A book published in 1993 The Seven Ages of Frank Lloyd Wright, written by Dennis Hoppen, observed that Lloyd Wright had a remarkable ability to absorb reversals and over time convert them into new periods of creativity.

It is this which makes Wright worth studying. The patrician who was never short of a word of self-praise ought not detain us. These traits probably had to do with a difficult upbringing: trauma created a sort of outer person which was secondary to the much more interesting inner creative life by which he really lived.

In interview, we meet this outer self; in his work the far interesting central force. Regardless, his life has a fascinating rhythm to it: Hoppen’s book shows that Wright experienced surges of creativity which were routinely checked by disaster. But these disasters seem to have gone deep into him, and by some mysterious creative process, engendered over time great leaps forward in his art.

Wright would often state that he didn’t decide to be an architect, his mother made that decision for him. She declared while Frank was still in the womb that he would grow up to create beautiful buildings and was so proactive in what was then a distant likelihood as to adorn his nursery with pictures of the great English cathedrals. Wright would later make it clear that he didn’t think anybody had taught him architecture telling Downs with his usual slightly prim arrogance:

I’m no teacher. Never wanted to teach and don’t believe in teaching an art. Science yes, business of course..but an art cannot be taught. You can only inculcate it, you can be an exemplar, you can create an atmosphere in which it can grow. Well I suppose I, being an exemplar, could be called a teacher, in spite of myself. So go ahead, call me a teacher.

Wright’s initial degree was in civil engineering but his ambition was to make it to Chicago; in fact, he left university just before completing his qualification. He may not have felt he needed a teacher. But a mentor, one feels, can be a quite different thing and in Louis Sullivan, of the firm Adler & Sullivan, that is what Wright found in spite of his own irascibility and the perennial failure to get on with people which would often crop up in his career.

Though Wright would make a habit of disparaging his contemporaries, Sullivan would be remembered fondly by Wright – though by no means so fondly as to make anyone think Wright himself was anything other than number one, or in his own confident estimation, “the greatest architect who ever lived, or will live.”

The trouble with Wright’s arrogance is that the architecture does tend rather to bear out his own high assessment of himself. Even as a young man he had already by 1900, almost single-handedly, invented prairie architecture, with a series of four houses which showed a completely undaunted sense of the possibility of American architecture, and by association American life. The European ideal, from Wright’s perspective, was all very well, but the greatness of European art had been arrived by being true to the history and values of that continent. Mightn’t something new be possible in this vast country?

And if something was possible, then what distinguished the American case from the European? The first thing was the sheer size of the country and therefore the space assigned to each individual. Europeans, and especially British people, have long since found themselves living on top of one another. Any visitor to the towns of America feels how different the demographics are: we feel the country’s enormity, its abundance, and tied to these things, the sense that Americans can live differently, which of course means in different buildings. Prairie architecture was Wright’s first attempt to be true to what now seems to us a fairly obvious reality. Many of these houses still stand today as he always said they would.

The great innovation here is the horizontal line which mirrors the great outstretched nature of America. For Wright, European architecture was pre-democratic or even anti-democratic and characterised by boxed rooms, which are ideal for establishing hierarchical systems. One thinks of the servants’ quarters, or the cut-off luxury of, say, the master bedroom in a typical European castle. Wright’s houses are different: the open floor plan which would go onto dominate, in another setting, office life, is really his invention.

But these insights were built on a deeper intuition which had to do with the need to respect landscape, making Wright the purveyor of what he called organic architecture. This meant that his architecture was meant to embody the essence of the land. Most famously, he once expounded his views on hilltop or hillside architecture: “No house should ever be on a hill or on anything. It should be of the hill. Belonging to it. Hill and house should live together each the happier for the other.”

Wright’s architecture belongs to the land – and he accentuated this idea by building often in stone and wood. The prominent central chimneys in these houses are intended to relate to the human heart – and there is perhaps the sense that Wright’s buildings correspond not only to the landscape they’re in but to human beings themselves: they are, perhaps, attempts to create functional counterparts to the American soul.

It all amounted to a great vision of democracy by a man who in his life was actually rather authoritarian. It is possible to find a contradiction in his life between his sense of himself as the isolated Great Man, and his oft-stated belief that American architecture cannot thrive unless it takes into account its founding principle of democracy.

These promising – indeed, exceptional – beginnings were soon to be upended by unthinkable tragedy. Wright, though married, had conducted a controversial affair with a married woman – and the wife of one of his clients – Mamah Borthwick. The press got wind of it all, and Wright built Taliesin in its the first incarnation in order to shield Borthwick from the press. Then on August 15, 1914, Julian Carlton, a male servant from Barbados, set fire to Taliesin, and then murdered seven people, including Borthwick and her two visiting children. It is hard to imagine what this must have been like for Frank Lloyd Wright, who happened to be away on business. But in time his reaction was remarkable:

There is release from anguish in action. Anguish would not leave Taliesin until action for renewal began. Again, and at once, all that had been in motion before at the will of the architect was set in motion. Steadily, again, stone by stone, board by board, Taliesin the II began to rise from Taliesin the first.

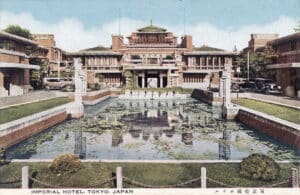

It is a splendid lesson about how to deal with setback: creatively. As Taliesin II was rebuilt, Lloyd Wright was working on a new phase in his career, when he accepted a commission to design the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo. This looks so different as to not seem to be from the hand of the same architect, but of course it’s in a different country and Wright was committed to an architecture which, to a near obsessive degree, took into account place.

Wright had thought through the viability of the structure – although sometimes this has been exaggerated a little. The structure did survive the Great Kantō earthquake of 1st September 1923 which and Baron Kihachiro Okura sent Wright the following telegram:

Hotel stands undamaged as a monument of your genius hundreds of homeless provided by perfectly maintained service congratulations[.] Congratulations[.]

Wright being Wright, he wasn’t about to keep this telegram from the press and the story did a fair amount to embellish his legend. In actual fact the central section had fallen through, and several floors bulged. It certainly wasn’t the least damaged building the earthquake.

But Wright had moved onto another phase, which is sometimes characterised as ‘monumentality’. His block houses such as Ennis House fall broadly into this category. One wonders whether in their scale and grandeur they reflect a growing awareness of America’s imperial destiny: they feel like houses which belong to a powerful people, and in the wake of the First World War, where American involvement had decisively tipped the scales towards the Allies, America’s self-image had shifted. It would be the world power, and here was the architecture to prove it.

But further disaster was round the corner, in the shape of another fire at Taliesin. On April 20th 1925, Wright noticed smoke billowing from his bedroom, and though on this occasion he was on site and able to call for help quickly, it was a night of high winds, and Taliesin II was destroyed along with much of the superb art collection which its owner had acquired while working in Japan. But again he was undaunted and took this loss as inspiration for Taliesin III which still stands today:

And I had faith that I could build another Taliesin! A few days later clearing away the debris to reconstruct I picked up partly calcined marble heads of the Tang-dynasty, fragments of the black basalt of the splendid Wei-stone, Sung soft-clay sculpture and gorgeous Ming pottery turned to the colour of bronze by the intensity of the blaze. The sacrificial offerings to — whatever Gods may be. And I put these fragments aside to weave them into the masonry — the fabric of Taliesin III that now — already in mind—was to stand in place of Taliesin II. And I went to work.

There is something magnificent about the simplicity of that sentence: “And I went to work”. In its confident forward movement we get very close to the essence of the man. From here, Wright would go on to his so-called ‘desert architecture’ phase – it was a difficult time for Wright personally and financially and he was forced to take on smaller projects such as Ocotilla and San Marcos in the Desert. This must have been relatively humbling, and of course the 1929 Great Depression was round the corner to humble him further.

By 1929, he could have been forgiven for thinking he’d had a life entirely comprised of setbacks. This huge decline in productivity led to another fallow period and then a period of low cost architecture characterised by his Usonian houses – small houses very private from the front and open at the back usually aimed at the middle class. The first such house is usually considered to be the Herbert and Katherine Jacobs First House.

Though this house, with its horizontality, and little carport, was perhaps a rather humbling project for a man to undertake who considered himself the equal, and indeed the superior, to the architects who made the Pyramids, Wright couldn’t quite refrain from couching it in the grandest terms possible: “The house of moderate cost is not only America’s major architectural problem, but the problem most difficult for her major architects.

As for me, I would rather solve it with satisfaction to myself and Usonia than build anything I can think of at the moment.” Usonia, incidentally, was Wright’s somewhat ludicrous term for America, but these houses are extremely beautiful and subtle. They feel as though they contain an earned wisdom. Indeed, perhaps as one looks at the wonderful Usonian houses, one can reflect that humility wasn’t a bad thing for Frank Lloyd Wright to get to know a little.

But humility wasn’t to be for the architect in the long run. The second half of his life contains fewer setbacks and much of his greatest work, especially the magnificent Fallingwater was still ahead of him, and that superb office space the Johnson Wax Headquarters, with its famous lily pad columns. Wright always said that it increased productivity.

As impediment fell away, and a greatness exactly like the one imagined for him by his mother was assured, Lloyd Wright settled into the grand and arrogant persona which Hugh Downs would come to visit in 1953, some six years before his death. But what’s more interesting than the man at the summit he became is the way in which he surmounted so many obstacles to get there.