BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

If you go to the National Gallery in London and visit, say, Room 32, where Mannerism is represented, there’s a good chance you’ll have it more or less to yourself. The same will likely be true if you walk past all those Renis and Guercinos and into Room 33, where Chardin’s Card-Players typically hangs. Things will likely get a little more crowded as you swing by the great British landscape painters in Room 34 – JMW Turner and John Constable.

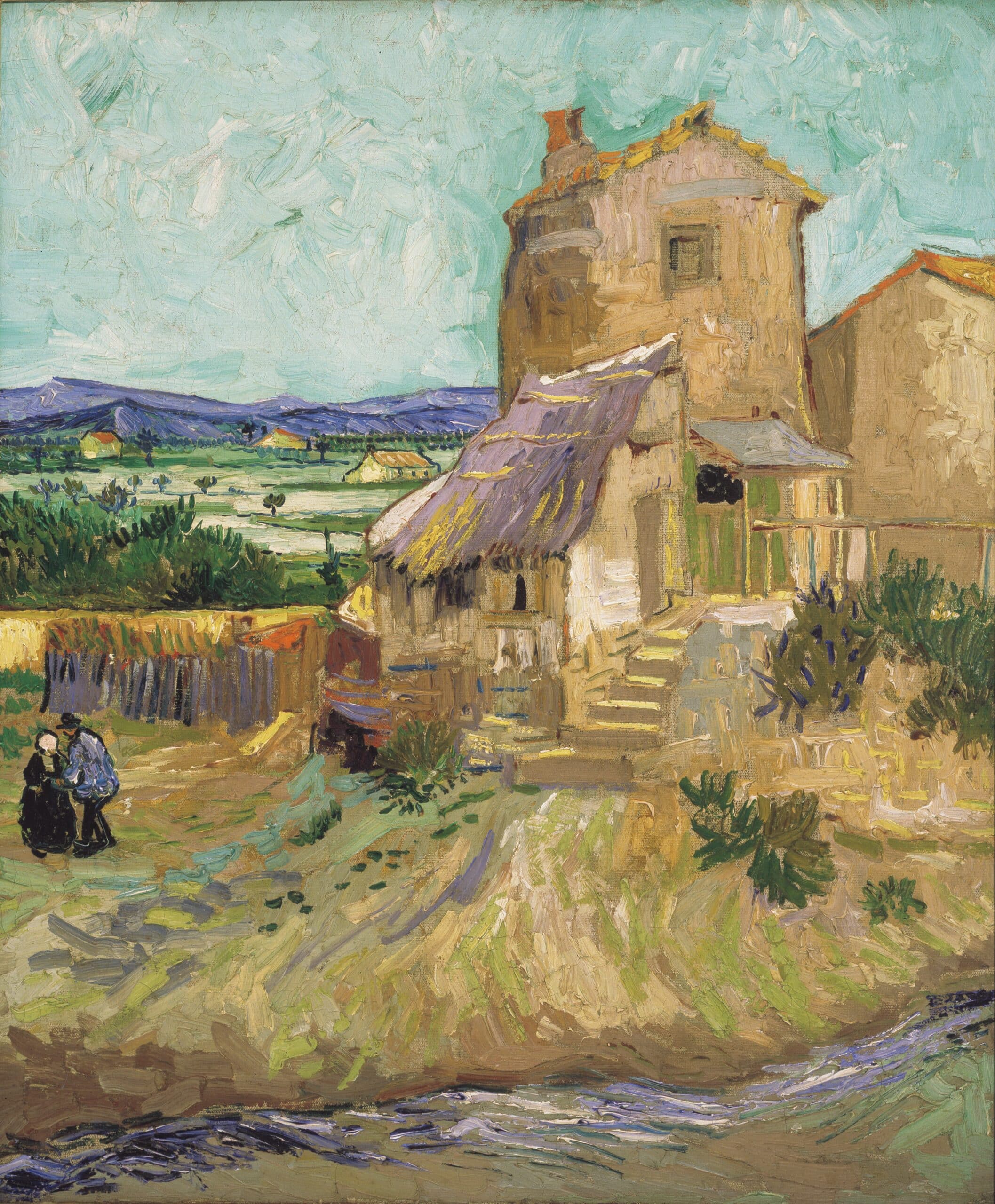

But something will happen as you enter Room 35: that’s because you’ve entered a room full of Impressionism. Come rain or shine, this will be the busiest part of the gallery. You probably won’t have Cézanne’s views of Mont Sainte-Victoire or any of the many Monets to yourself for very long, and you won’t have Vincent Van Gogh’s Sunflowers to yourself at all. Something has happened: you have crossed over.

Why is Impressionism, which loosely speaking turns 150 this year, such a big deal? None of the painters, with the possible exception of Vincent, had a natural talent to equal Rembrandt. I don’t think any of them create awe in the viewer as Turner does. If you want the oddities of daily life, you’ve got other Dutch painters like Hendrick Avercamp and Johannes Vermeer. For spiritual power, nothing beats Piero Della Francesca. But if the numbers tell the truth, something about these pictures makes us need them more than all of them put together.

One possible explanation is that they’re closer to us in time. The Impressionist movement was a response to the great essay ‘The Painter of Modern Life’ written by Charles Baudelaire in 1860, and which created a huge impact at a time when reading was the primary mode of entertainment. In this, the poet pleaded with artists to show the distinctive beauty of the modern world. The paintings in the Louvre, he says:

…represent the past; it is to the painting of modern manners that I wish to address myself today. The past is interesting not only for the beauty extracted from it by those artists for whom it was their present, but also, being past, for its historical value. It is the same with the present. The pleasure we derive from the representation of the present is due not merely to the beauty with which it can be invested but also to its essential quality of being present.

It is this ‘essential quality of being present’ which I think makes the crowds in the National Gallery flock in such numbers to these pictures.

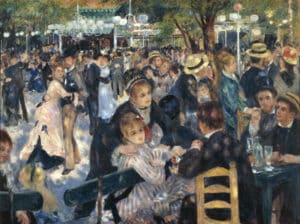

Admittedly the modern world meant something rather different in 1874 to what it means today, but still there is a sense in which these essentially secular images of pleasure and leisure chime. Though they might be low on depicting things like computer modems or airports, nevertheless they feel psychologically similar in some way to our own lives: they somehow have a legacy in us. It was the critic Louis Leroy who said after the first Impressionist exhibition in a somewhat derogatory way that the artists in the exhibition seemed intent on creating an ‘impression’ – by which he really meant a sketch:

Impression I was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it — and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more finished than this seascape.

This is the authentic note of the misfiring critic, who doesn’t even know that they have missed the main point, and so must satirise in a self-admiring vacuum. What Leroy failed to understand was that the world was now in a state of permanent psychological revolution, and that it would from now on move inexorably in the direction of hurry. We still live like this – dimly aware, even as we dash to the next meeting, that we have not enough time.

The eye too is in a hurry, never still, blinking continually, and alert to the latest shift. It too makes impressions. It was the Australian critic Clive James who towards the end of his life recalled his early time in Florence and the sight of the Bardi spire rising up over the medieval streets: “Glimpses are all you ever get,” he wrote. Leroy misunderstood that when it came to Impressionism, glimpses were being elevated to the realm of permanent art.

In doing all this, as Leroy also missed, a new attitude towards light was established and I think this is what really makes these pictures so exciting, and which gives them their addictive charge. Of course, all paintings have something to do with light: whenever you’re painting anything at all, you’re painting that – otherwise you wouldn’t be in the privileged position of being able to see.

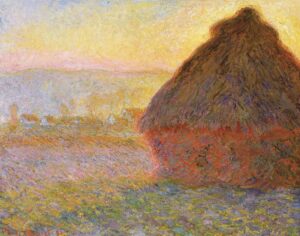

But Impressionism – and this is especially true of Claude Monet (1840-1926) – seems to mark a new kind of interest in light. Monet looks on water in a way different to the way in which, say, Leonardo da Vinci gave it his intention: in his Water Lilies, he wants to break it down, and consider what constitutes reflection and what amounts to water – and crucially, what that elusive entity light has to do with that relationship.

It is often said that Impressionism was the natural offshoot of photography. And so it was. But people rarely say how that relationship worked: the invention of the camera made people realise that the act of seeing was a more complicated business than had been supposed. The photographic image felt too clinical. Really, it was a kind of abstraction and this sent artists back to themselves.

If this amounted to a sort of crisis, it was a very exciting one. The sense of juxtaposition between a photograph’s verdict and the human eye’s experience meant that artists were suddenly compelled to consider the constituents of the world. They were helped in this by the way in which science had developed, especially with John Dalton’s discovery of the electron, and its secret and peculiar mystical vibrations.

But we tend to view Impressionism through a particular lens: we know that it would lead in time to the further fragmentation of Cubism and Abstraction. This in turn reminds us that Impressionism could easily have been a boring philosophical development – as did in fact happen to its successors. We do not flock to the work of Georges Braque – in fact, if it comes to that, I don’t think we really flock to Picasso. It’s all too intellectual and young artists should note how it is no coincidence that in avoiding this, the Impressionists have endured in a way the others haven’t.

But critics of the time did notice, with considerable prescience, the philosophical radicalism of Impressionism, if they usually failed to note the extent to which this was an underpinning and never intended to distract from the pleasure given to the viewer. The critic Theodore Duret wrote of Monet that he was “no longer painting merely the immobile and permanent aspect of a landscape but its fleeting appearances which the accidents of atmosphere present”.

This might have been true but it was a merely incidental truth. A sheer love of looking is what makes Impressionism so popular: it is full of an infectious enthusiasm for the visible world. The Impressionists knew that what they saw, faithfully interacted with, was enough. As Monet put it, with his legendary cantankerousness: “Everyone discusses my art and pretends to understand, as if it were necessary to understand, when it is simply necessary to love.”

Given all this, what contemporaries noted was that new aspects of life had been incorporated as subject matter by this new movement. Most of the references to classical mythology which had characterised the Impressionists’ great predecessor Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867) were gone (though they recur occasionally in canvases like Manet’s ‘Olympia’), so were the grand battles and historical scenes preferred by Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863).

Instead, the Impressionists depicted life’s intimate unfolding: in time they would give us the look of a haystack (Monet), an afternoon lazing by the Seine (Seurat), women bathing (Dégas), ballet-dancers practising their moves (Dégas again), a pair of boots (Vincent), and of course, a vase of sunflowers (Vincent). The gaze had been shifted temporarily away from the reconstruction of events theological and historical. Viewed in that way, and given what happened next, Impressionism is so valuable as a period in art history as it is a brief interregnum of actually looking at the world, rather than thinking about it in paint. This journey towards intellectual painting is already at its starting point in Cézanne’s cerebral canvases.

We tend to encounter Impressionism in grand art galleries with the best gilt picture frames round the pictures, and so we forget that these painters had a certain humility about their relationship to nature – though Monet certainly cannot have been called humble towards other people. In the way in which they faithfully set down what they saw, they were everymen – though in many cases everymen who happened to be geniuses. The artist beginning today could do a lot worse than look not towards the next fad but to what really lies outside their window for the inspiration that really counts.

The other thing we miss – and again it’s because reputation can sometimes intervene between us and what a painter’s real intentions are – is the wonderful oddity of some of the people knocking around Paris in the 1860s and 70s. For instance, the first Impressionists exhibition took place in the studio of a magnificent photographer called Nadar, who deserves an article in his own right.

He was not just a magnificent and original photographer but also an early enthusiast for ballooning; I think he was probably a fairly peculiar character in the best sense. But all the Impressionists had their unusualness from Monet’s ill temper to Renoir’s flightiness and indecision – not to mention Van Gogh’s occasional tendency, attributable today to bipolar disorder, to hug random people in the street.

We think of success as somehow preordained once it has happened, but it rarely looks like that at the time: actually it looks improbable for the reason that it’s usually unlikely to happen. Next time you see someone tinkering away at a picture or an invention with a look of concentration on their face, you may not be looking at someone slightly bonkers, but at a historical figure.

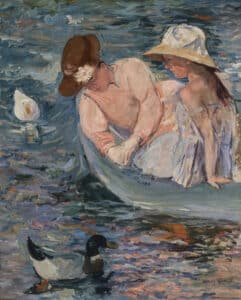

When it comes to Impressionism, the plight of women is another interesting one. The National Gallery of Ireland is this summer celebrating the 150th anniversary of the first Impressionist exhibition with Women Impressionists, a show which lasers in on four women artists integral to Impressionism – Berthe Morisot (1841-1895), Eva Gonzalès (1849-1883), Marie Bracquemond (1860-1914), and Mary Cassatt (1844-1926). All but Eva Gonzalès exhibited at Impressionist exhibitions, of which there were eight over the following 12 years.

It’s worth going to Dublin for – here are the women who broke free from being painted to doing the actual art. Morisot is easily the best known today – and in fact that was also the case in 1874, in that she was the only female artist to be featured in that first show at Nadar’s studio.

Throughout the Dublin exhibition we find images of maternal intimacy and gentleness. In Morisot’s work we are shown domesticity as it hasn’t been shown since Vermeer. But while Vermeer’s paintings sometimes point a lesson, or suggest an allegory, these are completely shorn of any morality: here we see, as in Cottage Interior, the quiet of the typical household shorn of explanation. This is just a girl in a beautifully lit interior, with a garden outside, some food on the table: life is like this, it seems to give such few directives. We live amid quiet mystery and many of Morisot’s paintings testify to this.

This sense of a welcoming simplicity repeats in the other female impressionists in the show. In Mary Cassatt’s drawings we can see that the love of Japanese prints wasn’t confined to Vincent Van Gogh – it was as much a fad of that time as primitivism would be at the start of the 20th century. My favourite picture of hers is Summertime where the water seems thicker, gloopier even, than it does in a Monet where we can hardly tell what is water and what is light. And yet on certain summer days, when it’s really hot, we find ourselves more conscious of the shade and the shadows, since we seek them out.

Summertime, 1894. Oil on canvas, 39 5/8 x 32 in. Daniel J. Terra Collection, 1988.25.

The Dublin exhibition confirms that Impressionism is still very much alive: it’s not really an aspect of art history at all, but part of our living reality. Today we find young artists falling over themselves to create gimmicks, and sustain an Instagram-driven brand: perhaps there are ways to build a brief career in that line, but it is impossible to create true art without reference to what is before our eyes in the universe itself. Impressionism is so valuable because it provides us with this encouragement. It sometimes seems behind us; really, it’s the way forward.