BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Grinling Gibbons’ works and artifacts from his life were exhibited together for the first time at Compton Verney Art Gallery and Park, writes Patrick Crowder

In 1671, at the age of 23, Grinling Gibbons had already become the most masterful woodcarver in the UK. He applied his natural, flowing style to detailed reliefs capturing the intricacies of the human form, mantlepieces depicting game and flowers, extremely fine replications of lace cravats, and many more ambitious projects. To stand before one of Gibbons’ pieces is to be transported to a world of minute detail and lifelike vitality. His carvings of ducks and lobsters look as if they could easily fly or scuttle away at any startling movement. A surviving example of one of his limewood cravats has maintained such detail that it is still possible to mistake the piece for genuine lace from a distance of more than a metre or two. His designs were so far ahead of their time that, even while Gibbons was alive, woodcarvers tried and failed to copy the masterfulness of his hand. Gibbons’ works can be found in situ at some of the country’s most important places, including St Paul’s Cathedral, Westminster Abbey, Hampton Court Palace, and Petworth House, cementing his place in the nation’s history.

To celebrate his 300th birthday, Compton Verney art has put together an extensive collection of his works and artefacts from his life which have never been displayed in the same place before. Gibbons was not only a pioneer of woodcarving and stonework, but also a keen entrepreneur who knew how to run a business and find patrons for his work. I spoke to Hannah Phillip, who is Programme Director and largely responsible for the exhibition, about Gibbons’ life, approaches to business and mentorship, and the lasting legacy he has left behind.

This could be Rotterdam

As it turns out, the celebrated British woodcarver was not born in Britain, but Rotterdam on the 4th of April, 1648. The name Grinling was derived from his mother’s maiden name, while his brother Dingly was given the maiden name of their grandmother. Throughout his life he was both a benefactor and provider of mentorship, and Philip tells me that his first apprenticeship likely took place near his home. “There have been different views on where Gibbons might have learned his craft, she explains. “The traditional one is that he was apprenticed to a master carver called Artus Quellinus who at that point was operating in Amsterdam and working on a major project, which was Amsterdam Town Hall,” Hannah said, “But equally, the other school of thought, which is very compelling, looks at Gibbons’ roots and what was going on around him.”

This new theory, developed by Ada de Witt, looks at the shipbuilding community in Rotterdam. In those days, the sterns of ships were adorned with intricate woodcarvings depicting a wide variety of scenes, and it is likely that Gibbons got his start on ships such as these.

“In Rotterdam there was a huge shipbuilding industry which required highly skilled carvers,” Philip continues. “The new thought is that he was more likely to be apprenticed locally to the Van Douwe family, whose workshops were very close to where Gibbons lived. I suppose whichever master carver or sculptor he was apprenticed to, we do know that it is very much how he would have developed his skills, and without that mentor, he wouldn’t have been able to go on to what he was able to achieve.”

The lessons Gibbons learned during his early years in Rotterdam would lay the foundation for him to become one of the most inventive, skilful carvers of his time.

London Calling

Gibbons left the Netherlands and moved to York in 1667, when he was 19 years old. Even at this young age, he was an extremely talented carver, producing detailed renderings of musical instruments, cherubs, and people while under the employment of carver and architect John Etty.

Four years later he moved to Deptford, another maritime town, and continued to hone his skills. It was there that one day, when Gibbons went out to a small thatched-roof house in a nearby field to find some peace to do his work, he was stumbled upon by the prominent diarist John Evelyn. Evelyn was so astonished by the intricate depiction of the Crucifixion Gibbons was carving that he decided to use his royal connections and introduce King Charles II to Gibbons and his work. In his diary, Evelyn wrote;

“I this day first acquainted his Majestie with that incomparable young man, Gibson, whom I had lately found in an Obscure place, & that by mere accident, as I was walking neere a poore solitary thatched house in a field in our parish neere Says-Court. I asked if I might come in, he opned the doore civily to me, & I saw him about such work, as for the curiosity of handling, drawing & studious exactnesse, I never in my life had seene before in all my travells.”

From that point forward, Gibbons became known as “The King’s Carver”, winning commissions for mantlepieces, intricate wooden cravats which could be mistaken for lace, and decorations for St. Paul’s Cathedral.

The Crucifixion panel Gibbons was working on became his primary showpiece to display his talent to prospective patrons, and his attitudes surrounding this masterpiece give us a glimpse into Gibbons’ business sense and self-worth. Philip explains how he used the Crucifixion panel to win commissions:“The Crucifixion panel became his CV in effect, and I think that’s the reason he was producing this virtuoso work. Yes, he wanted to sell it, and when John Evelyn asked how much it cost, he came back with a price of £200 pounds, which was a lot of money. He knew his worth. He played the cards of ‘I’m a humble carver learning my skill’ and all the rest of it, but I think we need to take account of the fact that he knew that he was very good at what he was doing.”

From Mentee to Mentor

After getting his start through apprenticeship, Gibbons took on apprentices of his own. He was a member of the Drapers’ Company and served on their Court of Assistants for 17 years, so we can see evidence of the carvers he apprenticed in their records. We ask Philip what apprentices meant for Gibbons and his work. “Gibbons undoubtedly would have passed on his skill to multiple carvers given the length of his career and the number of commissions he was given. We know that he took on apprentices because they are recorded in the Drapers’ records, and quite early on he took on an apprentice,” Philip says. “It would have provided him with some money – you had to pay for your apprenticeship – and it would also of course expand his capability to take on particular commissions.”

Some of Gibbons’ assistants would have been journeymen looking to hone their skills, as he was himself at 19. Others would have been comparative beginners given simpler tasks, working their way up and gaining valuable insight from Gibbons’ process. “There would have been a conveyance of knowledge and skills over time in the form of workshop practice and mentorship,” Philip argues. “Of course there was commercial motivation behind it, but I don’t think that diminishes what that workshop process achieved in bringing on new skill and talent and perpetuating his own vision and style.”

For Gibbons, apprentices allowed him to take on more commissions and to produce more work in his signature style. It is often difficult to distinguish the pieces made by Gibbons’ hands from those made by his apprentices, which is further evidence that he must have been a talented teacher. He was also not afraid to change things up if work wasn’t selling. Philips says he had a keen eye for shifting market demand. “He understood all the different key elements of running a good business – supply and demand, moving into more profitable areas and materials. He started off doing narrative panels but readily perceived that there was a market for decorative carving, so he certainly wasn’t so precious about his art that he would only continue in the way he wanted to. He comes across as someone who had really good business acumen and instinct.”

Gibbons today

Apprenticeships are still an integral part of woodcarving today, and most professional-level carvers and sculptors will have trained under a master of their field.

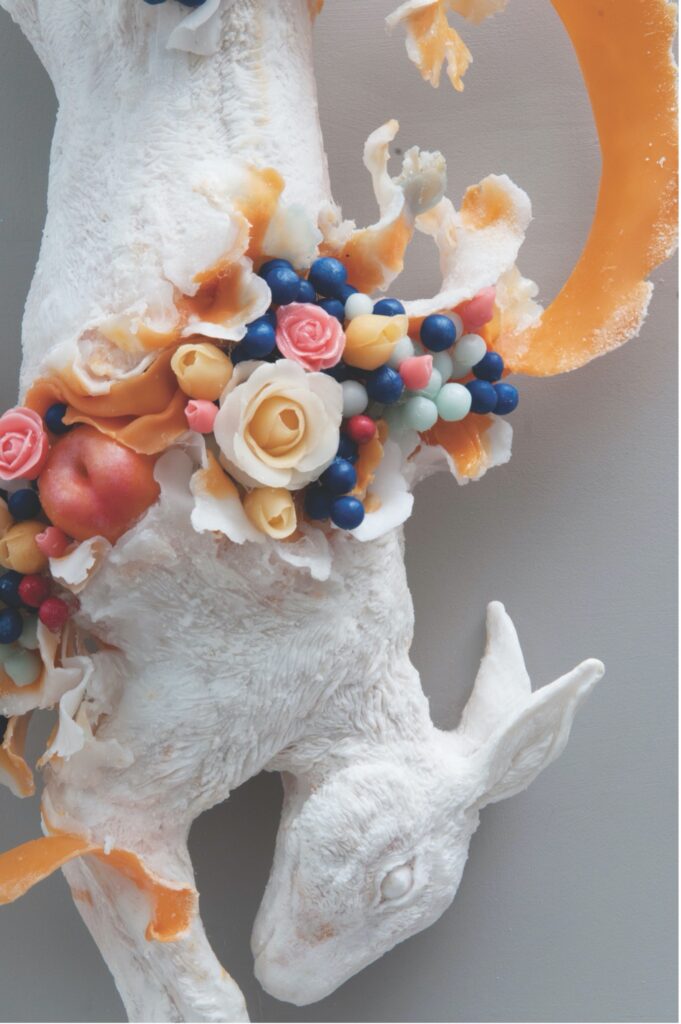

The legacy which Gibbons has left behind extends beyond sculptors and woodcarvers, inspiring artists who work with all media both in his time and ours. Even while he was still alive people attempted to copy his work, which was a sign of the influence his style had on the market. Now, artists such as Rebecca Stevenson have taken more interpretive approaches, exploring his themes and their meanings in new ways.

A lot has changed since the time of Gibbons, but one fact remains the same – art relies on patronage. Heritage crafts such as woodcarving fall in and out of style with the passing centuries, so there is always a real danger of losing them without some incentive for the unbroken exchange of knowledge between master and apprentice to continue.

To showcase Gibbons’ influence and to ensure that these skills are not lost to time, the Grinling Gibbons Society created the Tercentenary Award. This national contest sought up-and-coming carvers and sculptors from across the UK to produce Gibbons-inspired works in wood and stone. Prince Charles was a patron of the Grinling Gibbons Tercentenary award and even tried his hand at woodcarving as part of his quest to keep traditional crafts alive. Philip explains how the award helped young carvers develop their skills.

“The idea of the award wasn’t just to deliver prize money to aspiring carvers – it was actually to mentor them, making the process of producing the work part of the learning experience. Each artist was paired up with one or two master carvers to help them with the development of their ideas. We felt that was the most important part – so that whoever ended up winning wasn’t the only winner.”

Being an excellent carver, as the contest entrants were, is not always enough to win commissions. Philip has seen how practical experience with an art exhibition producing work to a deadline can help young carvers’ business acumen:“There’s a big chasm between going through a course and training to be a carver, and then actually getting your foot on the rung of doing it professionally,” she explains. “Whatever you learned at the training level, while very beneficial, doesn’t give you the commercial expertise and the ability to translate that to a business setting of producing things for clients.”

But what if no clients can be found? Since Gibbons’ time, styles have moved away from intricately carved wooden mantlepieces and wall-hung reliefs to a more mass-produced culture, and the furnishings which were once the bread and butter of the woodcarving community now have far less demand. Philip hopes that the exhibition will inspire people to take another look at modern work with roots in the style of Gibbons.

“It’s about educating up-and-coming carvers, but it’s also about trying to nurture some up-and-coming patrons – because without the patrons, there are no carvers,” Philips says. “By displaying these works in the exhibition, it gives an opportunity to see these artists’ works and maybe even consider commissioning something themselves.”

The exhibition Grinling Gibbons: Centuries in the making ran from the 25th of September, 2021 to the 30th of January, 2022 at Compton Verney Art Gallery and Park.