BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Georgia Heneage

You may not have heard of him but last week Matt Moulding became Britain’s most generous man.

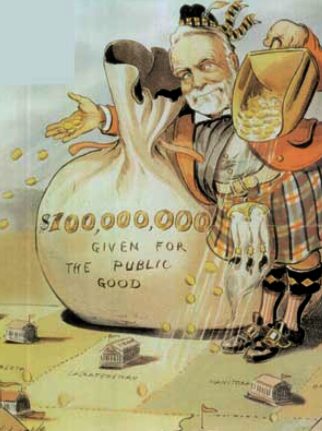

The son of a road-surfacer, Moulding is self-made: he left school at 16 to work in a local felt factory but returned to finish A-Levels after being tracked down by his economics teacher, who believed that he had great potential. He then worked for various tech firms before setting up The Hut Group, which floated on the stock exchange last September for £4.5 billion. Moulding has decided to give £100 million pounds of it to a domestic abuse charity -100% of which he could have received in rent payments from the business.

Such instances of generous philanthropy are not uncommon in an era in which billionaires are multiplying at a staggering rate – most of them tech oligarchs – at the same time as world poverty is soaring and the climate collapsing. Lord Sainsbury, the UK’s second biggest philanthropist, has donated tens of billions in the past decade to the Liberal Democrats, the arts, education and humanitarian sector, and the British Museum – to name a few.

But as a well-established and well-structured sector, what does charity mean in the modern age?

To answer this question we might revisit the complex and long-standing origins of ‘philanthropy’. It’s earliest form was almsgiving (giving money to the poor) in the medieval period, which was rooted in religious duty. In the 16th century more secular concepts of charity emerged from the schism between Catholic and Protestant (and their competing notions of what charity should be) during the reformation.

Then, at the beginning of the 17th century, Elizabeth I introduced a law making charities more accountable, after which the first legal definition of charities was created. This went on to form the basis of UK charity law.

The sector became much more systematic around the late 18th century, when modern concepts of corporations as standalone legal units began taking shape, and philanthropists pooled resources and combined their efforts.

Then, of course, came the Victorian age, where philanthropy sky-rocketed: the industrial revolution and the ubiquity of manufacturing jobs brought about increased poverty, and this led to more state involvement in welfare issues. With the onset of liberal politics and the Labour movement in the 20th century, philanthropy was brought under the bureaucratic wing of the government.

So where does this leave us now? Today philanthropy is so widespread that quite apart from roles within the charities themselves, ancillary jobs have grown up around the industry. Lawyers might specialise in charities. Bates Wells is arguably preeminent in the area, with Farrer & Co. another revered firm which offers opportunities. Banks and investment firms have professionals dedicated to advising clients on the ‘giving’ aspect of their portfolios. The charities themselves are more and more run like businesses, meaning that they require advice on a whole range of issues from HR and tech, to transactional activity and litigation aspects.

In 2021, the cultural prevalence of identity politics and human rights issues has fostered renewed interest in philanthropy. And Covid-19 has, as ever, made its mark in this sector too: charitable actions during the pandemic – such as the late captain Captain Sir Tom Moore’s charity walk or the countless other marathons people did in their back gardens – may be an indicator of a population shaken into giving back to the community and helping others during a collective crisis.

The figures certainly show this: according to a 2020 report by Charities Aid Foundation (CAF), though less face-to-face interactions during Covid meant physical fundraising declined, large and sustained “cashless” donations and general trust in charities increased.

Between January and June 2020, the public donated a total of £5.4 billion to charity – an increase of £800 million compared to the same period in 2019. And the charity sector may be one of the few positive instances of digitalization; research shows that social media is the biggest inspirer of donations and emails the biggest format of donating.

Yet a cursory glance over the history of philanthropy is enough to see how it has gradually changed from well-meaning charitable acts of well-endowed individuals to an industrialised sector; and how, in some instances, it’s been enveloped by the competitive wing of capitalism.

There has been a worrying number of cases of corruption and misspend funds in the charity sector, which has given rise to nicknaming some large charities “briefcase NGOs”- where the funding system is warped so that money goes directly into the pockets of those who run the organisation. As one Guardian article suggests, many NGOs start out with “noble intentions” – intentions which are soon corrupted by international funding agencies which “dictate” the terms and cause the NGOs to realign their priorities with those of the patrons.

It is proving difficult for charities to maintain integrity in the brittle and competitive world of NGOs; yet as the faultlines between the rich and poor widen, and the environmental crisis we face grows nearer, philanthropy’s role will become ever more necessary. Individual endowments – such as those given by the likes of Moulding, Lord Sainsbury and Bill Gates – are diamonds in the rough. But for ordinary people who want to give back and whose pockets are not so heavy, the path needs to become more transparent.