BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

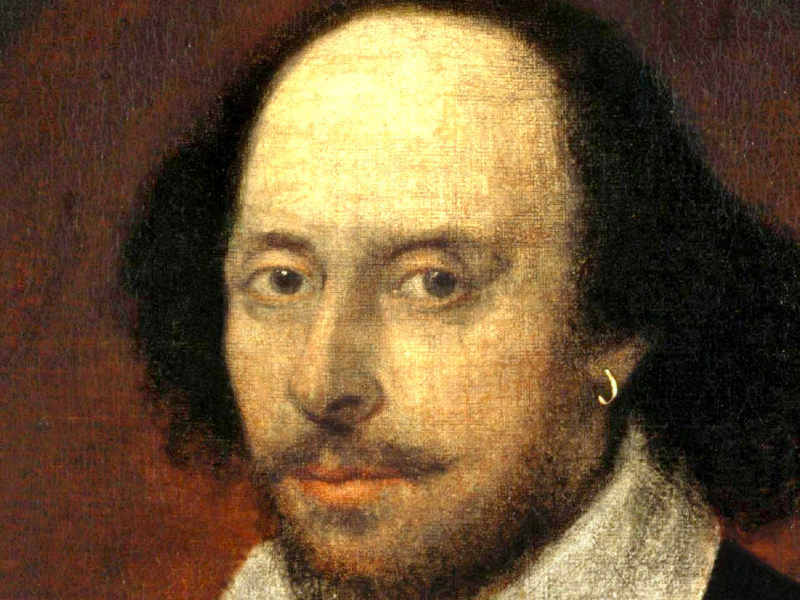

The life of William Shakespeare has lessons for how to make the best of your talents during a time of pandemic, writes Robert Golding

In January 1593, the Privy Council of Elizabeth I issued the following order: ‘Forasmuch as by the certificate of the last week it appeared the infection doth increase…we think it fit that all manner of concourse and public meetings of the people at plays, bear-baiting, bowling’s and other like assemblies for sports be forbidden.’

This was bad news for many, but perhaps especially so for a young playwright who was beginning to come out of the shadow of Christopher Marlowe and forge a place at the forefront of the city’s theatre. At the time of the plague’s outbreak, a certain William Shakespeare had begun to find his voice.

Though plague was a fact of Elizabethan life, it must have come as a setback. His life up until that point had not been without gamble. William – Will, as he appears to have been known to friends – had left his wife and family behind in Stratford-upon-Avon and embarked on a career in the slightly louche world of the contemporary theatre.

The language of the edict with its courtly leisure – ‘it appeared the infection doth increase’ – shouldn’t blind us to the cataclysmic impact on Shakespeare and his contemporaries. Shakespeare’s contemporary John Stow – responsible for so much of our knowledge of Elizabethan London – recorded that 11,000 out of 200,000 died between December 1592 and December 1593.

The Elizabethan plague was, of course, far worse than anything we have experienced in 2020. People died in the street, rendering death an ever-present aspect of daily experience. We might miss, for example, the force of the famous insult in Romeo and Juliet: ‘A plague on both your houses’. What is being wished here is something far more awful than we, even as we live out this unsettling year, can imagine.

It ought to be a certain comfort to us now, to realize that Shakespeare’s life – among the most marvelous that history records – was beset by plague at every turn. And those of us who fear even a vaccine won’t put an end to our woes might remind themselves that plague was both a constant and a mutating reality for Elizabethans.

There was a serious bout of plague in Warwickshire the year of Shakespeare’s birth; the young Will would not have been expected to survive. Whatever talk may have swirled about ‘a merrie meeting’ having precipitated the playwright’s death in 1616 at the age of 52, there is nothing to say it wasn’t the proximate cause of his death. We worry about a second wave of coronavirus – our finest poet existed within an unbaiting wave of mortality.

Yet he continued – and not only that, time and again reinvented himself. The plays and poems which follow on from the big plague years are evidence of a profound pooling of resources and a taking stock. Love’s Labor’s Lost, Midsummer Night’s Dream and Romeo and Juliet follow on from the plague year of 1593. They exhibit a richness, and even an urgency, difficult to discern in the ghoulish Titus Andronicus or the bombastic Henry VI trilogy, written the year before the plague struck.

But William Baker points out in his book William Shakespeare, that between 1603 and 1613, London’s theatre land was closed for 78 months. Though the poet inhabited a society without any social safety net, let alone the largesse of today’s furlough scheme, there are lessons here for today’s young people starting out on their careers.

In 1593, Shakespeare was swift to man oeuvre when the severity of that particular bout of plague became evident. Faced with an income gap due to a sudden pestilence, he was in no different a position to an airline pilot or live events manager today.

So what did he do? He launched himself immediately as a courtly poet. For a country boy, it was an act of tremendous gumption, under the patronage of the Earl of Southampton. We therefore have two epic poems – Venus and Adonis and the Rape of Lucrece – which might be termed plague poems. Each breathes freshness, health and life; they must have been cathartic to those reading them, and indeed these long poems were hits among the student population at the Inns of Court.

For some times, the theory has circulated – and been brilliantly argued on the website The Shakespeare Code – that Shakespeare was using existing connections to forge his career: it is argued that Shakespeare had in fact taught and conducted secretarial work in Titchfield, where the Earls of Southampton lived, prior to the plague. This might have particular resonance for those casting around for contacts during the time of coronavirus: open that contact book. It also shows the willingness of our greatest mind to undertake menial tasks if it meant getting in close proximity to someone with the power to make a difference to his life.

What is clear is that Shakespeare was flexible and imaginative; at the critical point, he was willing to imagine another version of his life. He also remained true to his gifts. There is a strong hint in Sonnet 111 that Shakespeare found playwriting a drudgery: ‘my nature is subsumed/ to what it works in like the dyers hand’. He seems to lament his low birth. But when the moment came, he didn’t attempt the impossible. There is a strong pragmatic streak about Will; he might seem in the stratosphere now but this was no dreamer.

What also might chime with today’s young is that he remained patient and took the long view. He might have been forgiven for thinking in 1593 that the long-term prospects for life in the theatre weren’t good. What was there to stop plague returning and scotching year after year of possible revenue? But he appears to have kept his options open, and retained connections within theatre land even while branching out into poetry. There is a strong hint throughout his career that Shakespeare had a quiet talent both for friendship – contemporaries would refer to him as ‘sweet’ and ‘honey-tongued’ – but also for business relationships. In his last will, he would bequeath memorial rings to the actors John Hemminge’s and Henry Condell; they would repay his memory by editing the First Folio in 1623, seven years after the poet’s death.

This was networking, as it were, from beyond the grave. The hard realities of inhabiting a plague-riddled society appear to have made Shakespeare not just a better poet but a better businessman. This has sometimes been an inconvenient fact to those who would have preferred the Bard to be more Keatsian – more head-in-the-clouds, and klutzy with money. The record shows he was anything but.

Instead, Shakespeare continually found ways to expand not only his poetic capacity and his knowledge of human nature, but also to develop what we now call his career. In 1594, he bought a one of James I would become the King’s Men: Shakespeare saw the main chance and took it. Again, there is a hint – but no real proof – that he was utilizing his connections. It has long been rumored that it was the Earl of Southampton who loaned Shakespeare the capital. If so, we might wonder whether he wisely used his time in lockdown to deepen existing connections.

There is an onwards pressure to Shakespeare’s life which suggests a refusal to become down-hearted from which we might learn. The year’s show him steadily more active both as a property owner in London and Stratford, as a shareholder in his theatre company, and as someone with small businesses on the side in malt dealing, in lending, even going so far as to turn a property he owned in Henley Street into a pub.

As for the plays, it’s true that they don’t always exist within a milieu of work which we recognize, unless that milieu is the court. But once you look past that you find a good deal is implied about loyalty and about the dignity of work, and indeed a certain amount about the kind of adaptability which we can vaguely detect in Shakespeare’s own life.

It has been said that the characters Shakespeare most admires are Horatio in Hamlet, Kent in King Lear; Cassio in Othello, and Enobarbus in Anthony and Cleopatra. These are the characters still standing at the end in the tragedies; those who will be charged with rebuilding the state. This a recurring type: the hard-working, flexible, loyal aide who becomes clearer in his moral purpose as difficulty mounts.

These are plays written by a man thrown back continually on his own resources, and who time again rose to that situation. William Shakespeare found new things within himself – new forms of language, yes, but also new forms of life. His relevance ought not to be surprising. Every period of history has found in Shakespeare a friend and teacher – but it’s fascinating during these unsettling times to see how much his life, and not just his poetry, has to teach us.