BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson

All the talk of the 21st century belonging to the Chinese isn’t likely to have been reduced by the spectacle of the Biden administration foreign policy in both Afghanistan and Ukraine.

But there is no doubt that the ‘demise of America’ narrative can be overblown. According to the Global Power Index, America remains ahead of all other countries on account of its economic, cultural and military power. It is too soon to announce its irrelevance, even if the image of an elderly president sometimes struggling to grasp the detail of problems does make one think inevitably of a decline straight out of the works of Edward Gibbon.

The truth is that America still matters, even if – and perhaps especially if – it can sometimes seem notable by its absence. Its economic policy continues to influence ours if only because it accounts for 14.7 per cent of all exports (as of 2021), including everything from boilers and nuclear equipment ($10.5 billion in 2021), vehicles ($8.19 billion), and pharmaceuticals ($5.10 billion).

As important as these statistics are, they feel limited as they can’t take into account the enormous impact of our cultural relationship. Not only is there the raw economics, but the back and forth of entertainment. The best statistic here is the number of streaming subscribers in the UK of channels dominated by an American understanding of the world. At the end of 2021, the number of Netflix subscribers stood at 14 million, a slight dip of 750,000 on the previous year. This is due to an increase of subscribers to Amazon which now has around 12.3 million and Disney which has swiftly taken considerable market share at 4.7 million. Is it any wonder that one often encounters people in the UK who speak with a slight New York or Californian accent, or that ‘wokeness’, a term coined in the US civil rights movement in the 1960s, should now be such a live issue within British society and in the British workplace?

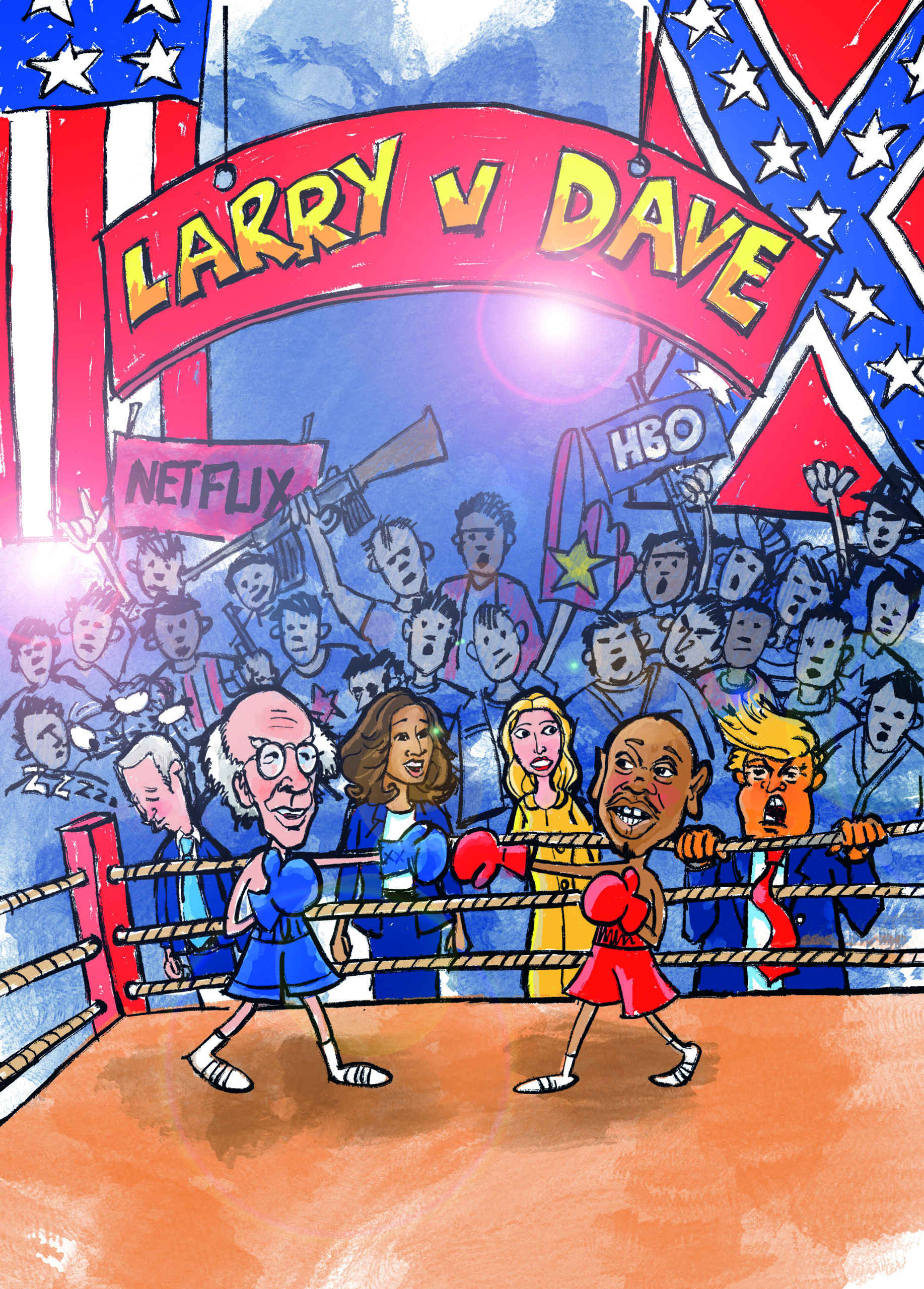

Larry v Dave

NowTV meanwhile stands at 2.2 million. In the context, that might not be worth mentioning, except for one important point: it is probably the best way to watch Larry David’s Curb Your Enthusiasm (2000-) – henceforth Curb as it is known to its fans.

Meanwhile, over on Netflix you can find the majority of the output of Dave Chappelle, a comedian whose worldview might on first inspection seem similar to David’s. This however turns out to be an illusion. Both Larry and Dave might be interviewed by David Letterman from time to time; each has starred on Jerry Seinfeld’s entertaining but slightly toe-curlingly chummy Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee (2012-); and both, of course, can make you laugh. To Brits, they are equally gigantic figures, sitting astride a huge economy: unfathomably rich spokespeople. They are creatures of power – and they probably don’t know from their American citadels how international their influence is, and might not care if they did. Even our own countrymen, Stewart Lee and Russell Howard do not seem to have comparable influence on our lives. Meanwhile, those who are of comparable importance such as Ricky Gervais and Steve Coogan have either moved to America (Gervais) or conquered the American market (Coogan). Both have paid court to David but not, so far as I’m aware, to Chappelle.

But if you watch each show, and follow through the implications of each laugh, you begin to realise that not only do Chappelle and David inhabit different worlds, but their worlds appear to be drifting further apart in a way which seems to say more about modern America than any statistic could.

Biographical clues

The clues are there when you look at the biographies of the two comedians. There have long been two Americas – the Conservative heartlands and the liberal coastlines.

The first of these is a predominantly rural world where the blue collar worker retains roots to the past. These states continually vote Republican and have pockets of Confederate sympathy. Here, gun ownership is an aspect of an immemorial tradition which dates back to the civil war and beyond, and where conservative social attitudes – especially opposition to abortion and a queasiness about the gains of the so-called LGBTQ movement – still dominate society.

The second is an urban counterpart: a place of crime, yes, but also of tolerance, of wealth, of kale milkshakes and sneakers – and above all, tech. In these places modernity reliably reigns. This has its political ramifications. At each presidential election, Democrats do well in the big cities, and among minorities – especially African Americans, and to a lesser extent, Latinos. The Republicans meanwhile have tended to do well in the south. All this is the legacy of Nixon’s controversial southern strategy, which was intended to cement the white vote, arguably by driving a racial wedge through the electorate.

The above is a simplification in many respects which is explored in different ways by both David and Chappelle. And yet it remains broadly useful: it is an aspect of American life which occurs too often to be discarded. It is also, as we see in the result of the 2016 EU referendum in Britain and in the recent French elections, an aspect of many modern societies.

Life of Larry

Larry David comes from the second of these Americans. He is a predominantly urban creature. He grew up in New York; one amusing leitmotif of his comedy is to parody his own distance from nature (though this hasn’t stopped him advocating for strong climate change policies). He once joked about his upbringing: “I grew up in Brooklyn. Of all the wonders and pleasures that Mother Earth has bestowed upon us, none of them could be found in Brooklyn.”

David continues: “There was nothing in nature we appreciated. Sunsets were mocked. The moon, in particular, held no fascination for anyone. I don’t think I ever heard anyone even use it in a sentence. Nobody ever said, “Hey, check out the moon!” We never gazed at it. We didn’t do any gazing.”

In Curb Your Enthusiasm, David’s long-suffering wife Cheryl, persuades Larry to go to the beach. He gesticulates at the sea and says, “I don’t get this fascination that people have with the ocean.” Cheryl replies: “Doesn’t it make you feel calm?” “No, it makes me feel aggravated that I don’t get something which other people are getting.” The perennial image of David is of someone schlepping through LA in the brilliant sunshine, amused by the quirks of the social code as it arises in cities.

Sometimes an aspect of rural America will intrude on his life. In Season 11 – which aired at the end of 2021 – Larry bumps into a Klu Klux Klan member and accidentally spills coffee over his outfit. The comedy of the situation is that Larry then bends over backwards to make sure he rectifies that wrong by taking it upon himself to do his laundry. This in turn leads to an encounter with a cow on a farm: a rare moment in Curb when we leave the streets of LA.

The Larry character in Curb doesn’t need to work since he is based on a counterpart of David’s own self who has long ago achieved unimaginable wealth thanks to the syndication of Seinfeld episodes. He has infinite leisure to follow up on any quirk of modern morality – to question an urban society which constantly seems to him to be filled with surreptitious selfishness, or contradiction.

It can make for remarkably rich comedy. But sometimes it reveals its limits unknowingly. There was a story recently of Larry David at Martha’s Vineyard bumping into Alan Dershowitz. Dershowitz, a constitutional lawyer best known today for having spent much more time with Jeffrey Epstein than most would think acceptable, was astonished to be accosted by David who began to quiz Dershowitz about his ties to the Trump administration.

According to reports, Dershowitz told David, “We can still talk, Larry.” David replied, “No. No. We really can’t. I saw you. I saw you with your arm around [former Trump Secretary of State Mike] Pompeo! It’s disgusting!”

We might very well disapprove of the Trump administration, but there is just a whiff here of censorship, of the inability to understand why someone should wish to hold a certain viewpoint – and therefore seek to suppress that viewpoint at the same time.

Dershowitz later summarised his views about the encounter: “Larry is a knee-jerk radical. He takes his politics from Hollywood. He doesn’t read a lot. He doesn’t think a lot,” adding, “It’s typical of what happens now on the Vineyard… People won’t talk to each other if they don’t agree with their politics.”

As it turns out, David was in Martha’s Vineyard in the first place to celebrate that notably hypocritical gathering, former President Barack Obama’s 60th birthday party. This unmasked affair showed all too clearly the real feelings of powerful people on the left about pandemic era restrictions: that they could be jettisoned when they felt like i t.

t.

Curb Your Enthusiasm itself sometimes displays something like this narrowness. In a recent episode David goes to pitch his latest comedy to Hulu and has some easy banter with the TV studio types. David points to three executives on the couch: ‘Did they like it?’ Then, mindful of the way in which pronouns are changing, he points to one of them: “Are you a ‘they’?” She says: “I’m only a they when I’m with other people.” David points to the next person and says: “Are you a they?” “No, I’m gay.”

This is fine in all respects except a crucial one: it isn’t funny. In many other situations in Curb, David will double down on an absurdity like this; he will probe and examine behaviour and say the hitherto unsayable. An equivalent scene might involve David questioning woke orthodoxy. But instead here, he laughs and waves it away. He can’t imagine a society where gender fluidity is challengeable and therefore a potential subject of humour. In reneging on a real joke here, he shows his acceptance of a particular kind of leftist politics. Powerful as he is, he can’t go up against it – it would leave him friendless in the cities – New York and LA – where he has his home.

Sense of Community

By contrast, Dave Chappelle grew up in Ohio and despite acquiring great fame and riches, returned there. His comedy is shot through with a profound sense of community – both in respect of the locality, Yellow Springs, where he has spent his life, and in respect of his commitment to understand the African-American experience.

In Larry David’s world, community is occasionally glanced off – for instance, there is one episode based around a man with a toupée’s apparent treachery against the bald community. But more generally, David’s sense of allegiance is to Hollywood. This is the case both in respect of those narratives which revisit his friendships with Julia Louis Dreyfus, Jason Alexander and Jerry Seinfeld and in the almost endless stream of celebrity cameos.

His allegiance to the Jewish community is, of course, implicit throughout although it is interesting that this is constantly subverted. For instance, in an early episode he insists on the right to sing a passage from Wagner’s beautiful instrumental Siegfried Idyll. When someone overhears him and calls him ‘a self-hating Jew’, Larry retorts: ‘I may hate myself but it has nothing to do with being Jewish’. This is a brilliant episode, which asserts an essentially secular narrative whereby Wagner’s anti-Semitism isn’t sufficient reason to ignore the magnificent music he was able to compose.

David’s Jewishness is primarily tied to his justified sense of belonging to a long list of brilliant Jewish comedians, through Mel Brooks, who has appeared in Curb, and Woody Allen who hasn’t. (David though did appear in Allen’s 2009 flop Whatever Works). He belongs to his fellow comedians. As so often happens when people become famous, they prefer to be around people who have gone through similarly surreal experiences, of becoming known and talked about, photographed and idolised, and misunderstood – and deemed immortal when mortality remains their lot.

There is a world of difference in others words between David’s essentially secular relationship with Judaism, and Chappelle’s profound exploration in his comedy of the African-American experience. Both are funny comedians, but Chappelle is the braver. Chappelle has what George Orwell, though never the funniest of men, called in relation to his own polemical talent, ‘a power of facing unpleasant facts.’

Chappelle won fame and riches with Chappelle’s Show, buy decided to tear down the show rather than not be true to himself. In one standup show, around the time when he was considering departure, Chappelle found himself interrupted by members of the audience yelling a catchphrase from the show “I’m Rick James, bitch.” Chappelle left the stage and when he returned said: “This show is ruining my life.”

Precisely what triggered his eventual departure – which did him immense short-term financial damage – is still a mystery although we know a little more now after an interview with David Letterman on Netflix’s slightly embarrassingly named My Next Guest Needs No Introduction. Here, Chappelle talks of a laugh having been too easily won – enough to make him queasy about the whole nature of the comedy he was practising at that time. He said: “I was doing sketches that were funny but socially irresponsible. I felt I was deliberately being encouraged and I was overwhelmed.” On another occasion, he said: “The hardest thing is to be true to yourself, especially when everybody’s watching.”

Comedy is here deemed to be of the utmost importance; Chappelle is proclaiming that it matters at the level of the soul. I can’t see that anybody else has spoken about comedy in this way before.

Being true to himself meant returning to the circuit, and playing comedy clubs. He would rebuild his art. Insodoing, he has made sure that he has done more than anyone alive to ensure it merits this noun. He has done so by making sure he isn’t only funny. He is also thought-provoking.

The Chappelle art can be seen on Netflix in a series of specials: Equanimity (2017), The Bird Revelation (2017), Sticks and Stones (2019) and most recently The Closer (2021).

All these have been to some extent maligned by the transgender community, but there has been a sense of mounting rage since The Closer, which caused a good deal of disquiet at Netflix, leading to a showdown where some employees walked out.

This particular special needs to be watched rather than pontificated about.

In the first place, what is it saying? Chappelle is predominantly motivated in his comedy by community, and by a desire to not let the black American experience of marginalisation be backgrounded by another marginalisation – that of the trans people. He doesn’t say that ‘wokeness’ or the plight of the LGBTQ movement is a symptom of white privilege – but he does categorically reserve his rights to make jokes about that possibility. He is saying that it is not off limits, and he’s right about that. In truth, sensitivity is often funny as it hints at insecurity; this in turn suggests some kind of incompleteness within society, meaning that a joke in that direction contains the possibility of catharsis. This is what Nietzsche meant when he wrote that a joke is an epitaph on the death of a feeling. Sensitivities deserve to be laughed away if they are ultimately groundless. This is different to mocking what is sacred. In fact, true sacredness can stand to be mocked since it will have a secure basis in fact.

In Chappelle’s case, he is surely right that we must resist the temptation to say: ‘I am persecuted’ – especially if you will then be upset to hear the retort, ‘No you’re not.’ And what makes him able to say this? It is the whole gigantic inheritance of slavery, an experience which really was appalling, and which really does take some getting over. He is insisting on his right to check whether trans persecution is definitely persecution seen by the harsh light of the African-American experience. Insodoing he is speaking up for the freedoms people already have, so that they cannot be better protected.

At times, Chappelle’s humour automatically aligns him with those feminists who have been prepared to affirm the primacy of gender in their own experience, most famously JK Rowling. Here is Chappelle’s most shocking joke in The Closer, with apologies to the faint-hearted for the bad language: “Gender is a fact. Every human being in this room, every human being on Earth, had to pass through the legs of a woman to be on Earth. That is a fact. Now, I am not saying that to say trans women aren’t women, I am just saying that those pussies that they got … you know what I mean? I’m not saying it’s not pussy, but it’s Beyond Pussy or Impossible Pussy. It tastes like pussy, but that’s not quite what it is, is it? That’s not blood, that’s beet juice.”

One must first note the compression: it took JK Rowling thousands of words to say this on her blog – and there were no laughs, and so no Nietzschean catharsis. Her seriousness has left her far more vulnerable to attack than Chappelle. When the LGBTQ community reacted to this, there was talk of Chappelle attending a meeting with campaigners within Netflix.

Chappelle’s statement was typically robust: “I said what I said, and boy, I heard what you said. My God, how could I not? You said you want a safe working environment at Netflix. It seems like I’m the only one that can’t go to the office anymore.”

In the special itself, Chappelle also details the beautiful story of Chappelle’s friendship with Daphne Doran, a trans woman comedian. In the special Chappelle recalls Doran saying: “I don’t need you to understand me. I just need you to believe I’m having a human experience.”

In actual fact, nothing could be more affirming about Doran’s experience than Chappelle’s brilliant set. As Andrew Sullivan put it in The Weekly Dish: “And, through the jokes, that’s what Chappelle is celebrating: the individual human, never defined entirely by any single “identity,” or any “intersectional” variant thereof. An individual with enough agency to be able to laugh at herself, at others, at the world, an individual acutely aware of the tension between body and soul, feelings and facts, in a trans life, as well as other kinds of life.”

And so there’s a paradox here: that Chappelle’s understanding of community is built on the freedom of the individual, not on herd mentality.

If this is compared to the scene with Larry David in the Hulu office, we can see how far apart the two are: David’s sense of community is too cosy, it’s to do with leaving those alone who might cancel you, because that would be very tiring.

It is difficult to imagine anyone at any streaming service walking out after seeing a Larry David special. He’s not near enough the edge for that anymore, though he once was.

Inflexible politics always works against comedy. David’s sense of self is to do with being a Democrat – and specifically, a donor to the Democratic Party. As Dershowitz points out, Larry David is probably in the last analysis not particularly interested in politics, and it’s this which makes him vulnerable to being political since he’s unable to see, for instance, the flaws in the Democratic Party, or really how similar the two main parties are in the United States.

All the Presidents’ Men

There is a scene in the tenth episode of the fourth season of Curb called ‘Opening Night’ where David is finally about to hook up with Cady Hauffman. As they are kissing, David spies a portrait of George W. Bush on her dressing-room wall and breaks off the embrace. “Are you – a Republican?” Hauffman rolls her eyes: “Yes, Larry.”

It’s a funny scene because it highlights Larry’s own dogmatism: it satirises the polarisation of America. Larry David the Democrat can’t let go his dislike of the 43rd President just for a moment, or even explore whether that dislike of Bush is relevant enough at that point to suspend a possible romance. But at the same time, the question remains: “Does David know enough about politics to be sure the joke is as funny as he thinks it is?” Christopher Meyer recently noted in Iain Dale’s The Presidents that George W. Bush was intelligent on first meeting: this is not information that can co-exist with this scene.

David recently gave an interview at the ‘Netflix is a Joke’ festival where he was asked why he hadn’t been cancelled yet. “It’s a very good question. I don’t know why. I don’t like to think about it too much.” The answer is that he has challenged every orthodoxy apart from Democratic-Hollywood orthodoxy. David famously appeared on Saturday Night Live in the lead-up to Trump’s election and called him a racist. The appearance had a staged feel and probably only served to normalise Trump on national television. But it showed that David’s thought is often reductive: Bush is stupid, Trump is a racist. A man who is unparalleled at reading nuance in the situations people get themselves into, can’t apply those gifts to high politics.

It’s for this reason that it’s impossible to imagine David being rugby-tackled by someone on stage as happened to Dave Chappelle recently. Chappelle’s political comedy is more nuanced. In Equanimity, he describes Trump supporters as ‘decent folk’ adding that he ‘felt sorry for them’. Chappelle continues in that hypnotic voice of his: ‘I saw some angry faces and some determined faces, but they felt like decent folk… I know the game now. I know that rich white people call poor white people ‘trash.’ And the only reason I know that is because I made so much money last year, the rich whites told me they say it at a cocktail party.’

In this we see how both Chappelle – and David – might be termed rich outsiders. Both play on this. But what is crucial is where you end up living once you become famous. David is one of LA’s most famous residents. As the commentator Dr Randall Heather recently told me: “The thing to know about California is it’s really another planet”.

It’s Chappelle who has retained that sense of place – enough to attend a 2022 council meeting around a housing proposal in Yellow Springs, Ohio – and who therefore has his ear to the ground. Insofar as he can be, Chappelle is accessible. In the Trump passage I quoted above, he is to some extent alongside his fellow people, as is shown in the punchline: “I stood with them in line like all Americans are required to do in a democracy – nobody skips the line to vote – and I listened to them. I listened to them say naive poor white people things,” he said. “Man, Donald Trump’s gonna go to Washington and he’s gonna fight for us”. “I’m standing there thinking in my mind, ‘You dumb motherfucker. … You are poor. He’s fighting for me.”

The Unforgiven

Chappelle’s is a new kind of comedy: it is incantatory. Whole passages can pass without a joke – and his jokes when they come are never predictable. It is a highwire act. We watch him delving the truth, yes, but sometimes the experience can be more uncomfortable than that: it can be as if he is probing you, the viewer. You emerge on the other side of his sets changed – as Chappelle no doubt did too in the writing of them. Larry David’s comedy contains marvellous moments – if you don’t know David’s comedy, just google ‘Palestinian chicken’. But his comedy, rooted in Hollywood mores and assumptions, doesn’t seem to work quite so well in the post-woke landscape since it cannot, without alienating his audience, address the question at all.

This means that David will, more and more, have to resort to slapstick comedy which is the opposite of the incantatory humour of Chappelle. This isn’t necessarily terminal as David is good at this kind of comedy: one of the abiding images of Curb is of David grimacing as he looks back while someone ridiculously chases him down the sunny streets of California. In another episode The Bare Midriff, the episode ends with David hilariously hanging off a building, clutching at a girl’s tummy. I’ve always thought that this episode showed David at his best: like Tom Stoppard does in After Magritte, it was as if he had worked backwards from a preposterous image to figure out how we got there. It is gloriously silly. Comedy should always have room to be that. It might even be said that Chappelle doesn’t have David’s range, not least because he is working in the monologue form and David has successfully updated the comedy drama.

But it is Chappelle’s comedy that is for this time – however uncomfortable that might make some of us feel, and however difficult that might be for all of us to say. The eleventh season of Curb finally showed David running out of invention, adrift in 2021, whereas Chappelle is very much of it.

But we need both of them, because both are revolutionaries. The great sitcoms of the UK function on the basis of the predicament of the man in the middle of society, who must both suck up but is also able to punch down. Basil Fawlty has Manuel to berate, but must placate his wife and his guests. Alan Partridge has Lynne to do his bidding, but longs to please the TV bosses who might return him to fame. David Brent has Gareth beneath him, but head office, in the shape of Neil, above him, and so on and so forth.

David’s achievement is to create a comedy around someone who is financially impregnable and feels no need whatsoever to impress anyone. If Seinfeld was, famously, a show about nothing, then Curb, is a show about someone who cares about nothing. Perhaps it is even the first true atheistic comedy, in that the protagonist feels no existential anxiety whatsoever: this liberates Larry, the character, to oppose what he views as absurd in the people around him.

Chappelle’s comedy is to an extent few have realised religious comedy, albeit delivered in a secular setting. Chappelle is a Muslim convert, but he has also been called by Christianity Today, the ‘cultural pastor we need’.

He has said: “I don’t normally talk about my religion publicly because I don’t want people to associate me and my flaws with this beautiful thing. And I believe it is beautiful if you learn it the right way.” When Chappelle talks about this side of his life more elaborately to David Letterman, we are left with a sense of man for whom comedy has a profound moral purpose. It is a comedy which looks to transcend spiritual anxiety.

Sorry Seems to be the Hardest Word

And so we are left with two comedians who represent two Americas which are becoming increasingly separate from one another – as we see every time an election rolls around. The question arises as to whether these two versions of America can be reconciled with one another.

It would be foolish to place limits on what is possible, especially in America, that most dynamic of places. But one interesting leitmotif in both comedians is apology. Larry’s character is always saying sorry: “I’m apologising all day!” as he says in one episode. But it is always a sorry which is done out of expediency: he will be saying sorry again tomorrow. Again, David’s is not a comedy which leads to discovery, but which instead orbits a set of received truths.

Chappelle, too, has his stubborn streak. As he put it in his famous statement following the furore at Netflix over The Closer: “I am more than willing to give you an audience, but you will not summon me. I am not bending to anybody’s demands.” My sense is that these two Americas will never in the end apologise to one another, just as Trump won’t admit defeat in the 2020 elections.

Is comedy ever forgiving? You have to go quite a long way back for that. Since the satire boom of the 1960s, where comedy was aimed specifically at authority, the very notion of comedy has drifted free of its original meaning.

In its essence a comedy is a story where the characters come to a prosperous conclusion. That is why Dante could write so much about Hell and still call his book a Commedia – because the protagonist ends up in Heaven. Likewise in Shakespeare’s comedies, as in Dickens’ novels, there is always a certain sorting at the end where the good end well, and the evil are punished. Marriages happen; it’s forgotten that there’s such a thing as funerals. David has done more than anyone since Dickens to restore the word to its original meaning. His LA really can seem a place of no death. If we take moral evil as the only death we should really fear, then we can see that Chapelle’s comedy wishes to defeat death.

Whether reconciliation is possible for the United States of America remains to be seen. But the country is plainly large enough to admit almost any paradox: it is kind and cruel, beautiful and ugly, funny and serious and so on. It evolves and alters, and has always been a place of unusual hope – and forgiveness can be catching when it does spring up. But for now, it is clearly in a state of acute tension. To see that, all you have to do is go to Now TV or Netflix and press play.