BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson

Ten years after his death, Leonard Cohen remains an object lesson in how a career can evolve without a person ever losing themselves. These days we speak endlessly about “the pivot” — about rethinking one’s direction, about finding transferable skills — but Cohen lived the pivot decades before the word became fashionable. He was, first of all, not a singer but a novelist and a poet: an already accomplished literary figure in Montreal with two novels and several poetry collections behind him. And yet he found himself in his thirties living in a house without heat on the Greek island of Hydra, realising he could not make a living from literature. “I found out,” he said with his wry self-awareness, “that poetry was not a way of life. It was a verdict.”

So he made a choice. He decided that if he were ever to sustain himself, it would have to be through songwriting. But what is striking is that he did this without surrendering his voice. Most people pivot by dilution — toning down their eccentricities, turning themselves into palatable versions of what the market wants. Cohen pivoted by intensifying. The songwriter who arrived in New York in the mid-1960s, painfully shy and unsure of his singing voice, wrote songs that sounded as though they had been waiting for him all along. Years later in one of his greatest songs, ‘The Tower of Song’, he would announce with infinite confidence that he “was born with the gift of a golden voice” but I’m not sure it felt that way early on in Greenwich Village.

But an awareness of his gifts, often humourously expressed, if a leitmotif in his career. “I have the gift of the long line,” he would later sat — a phrase that explains almost everything about what makes his lyrics great: the ability to let an idea unspool, clause by clause, as though thought itself were singing.

The early songs that emerged from this pivot remain among the most atmospheric and specific in modern music. Take ‘Suzanne’. It is almost a blueprint for his method: an observational exactness (“the sun pours down like honey / on our lady of the harbour”) combined with a mystic undertow. He writes with the clarity of a poet but frames his imagery with the restraint of someone who knows that revelation must be offered slowly. What makes Suzanne so good is that the specificity leads you into transcendence: a cup of tea, an orange, a river, a church — details that unlock the metaphysical. We’re never quite sure what it is about Suzanne which makes her so extraordinary and this means we continue listening to the song, thinking this time around we might just find out.

Cohen once said: “If I knew where the good songs came from, I’d go there more often.” The remark is modest, humorous, and entirely sincere. His songs sound effortless, but effort was their secret architecture. He was famous for painstaking revisions — dozens of verses abandoned for a single surviving line. His life teaches us that the real work is invisible: the long struggle beneath the eventual simplicity.

There is an amusing story of Dylan and Cohen together, trading stories about the art of songwriting. Dylan asked Cohen how long it had taken him to write ‘Hallelujah’. Cohen said it had taken 10 years. Cohen asked how long it had taken Dylan to write ‘Just like a Woman’. “About five minutes,” came the reply. On another occasion, Dylan said to Cohen: “You’re number one, Leonard – but me, I’m number zero.” This, as is often the case with Dylan, is both true and extraordinarily arrogant. Dylan is reminding us that there are infinite possibilities with his songs – Cohen’s perhaps feel more tailored to Cohen.

Perhaps that’s why Cohen’s story is also one of low points. The most famous again concerns Hallelujah, now one of the most universally recognised songs in existence. It was rejected repeatedly by Columbia Records; the label deemed the album it appeared on commercially unpromising. It took Dylan championing the song in concert, and then later Jeff Buckley’s haunting cover, to bring it properly to public attention. Cohen responded characteristically: “When I wrote ‘Hallelujah’ the only person ultimately interested in it was myself.” To be fair, his own recording remains very much an acquired taste and the suspicion remains he didn’t quite record it right the first time around. Even so, there is a lesson here for anyone labouring on work that seems ignored: if you believe in its truth, you stay with it. Sometimes culture takes a while to catch up.

Cohen is the sort of questing man who will do his own thing. For instance, there was also the monastery — five years from 1994 to 1999 at Mount Baldy in California, serving as assistant to a Zen master, waking at 3 a.m., living quietly, disappearing almost entirely from public life. Most careers cannot absorb such absences. But Cohen’s could, because he understood something profound: that pauses do not always break a career; sometimes they deepen it. A life that includes periods of retreat can be richer than one spent in constant visibility. “The less I say,” he once remarked, “the more room there is for other things.” The other things, in this case, turned out to be the maturity and stillness that inform his later work, and which is best heard on that extraordinary late masterpiece ‘You Want It Darker’.

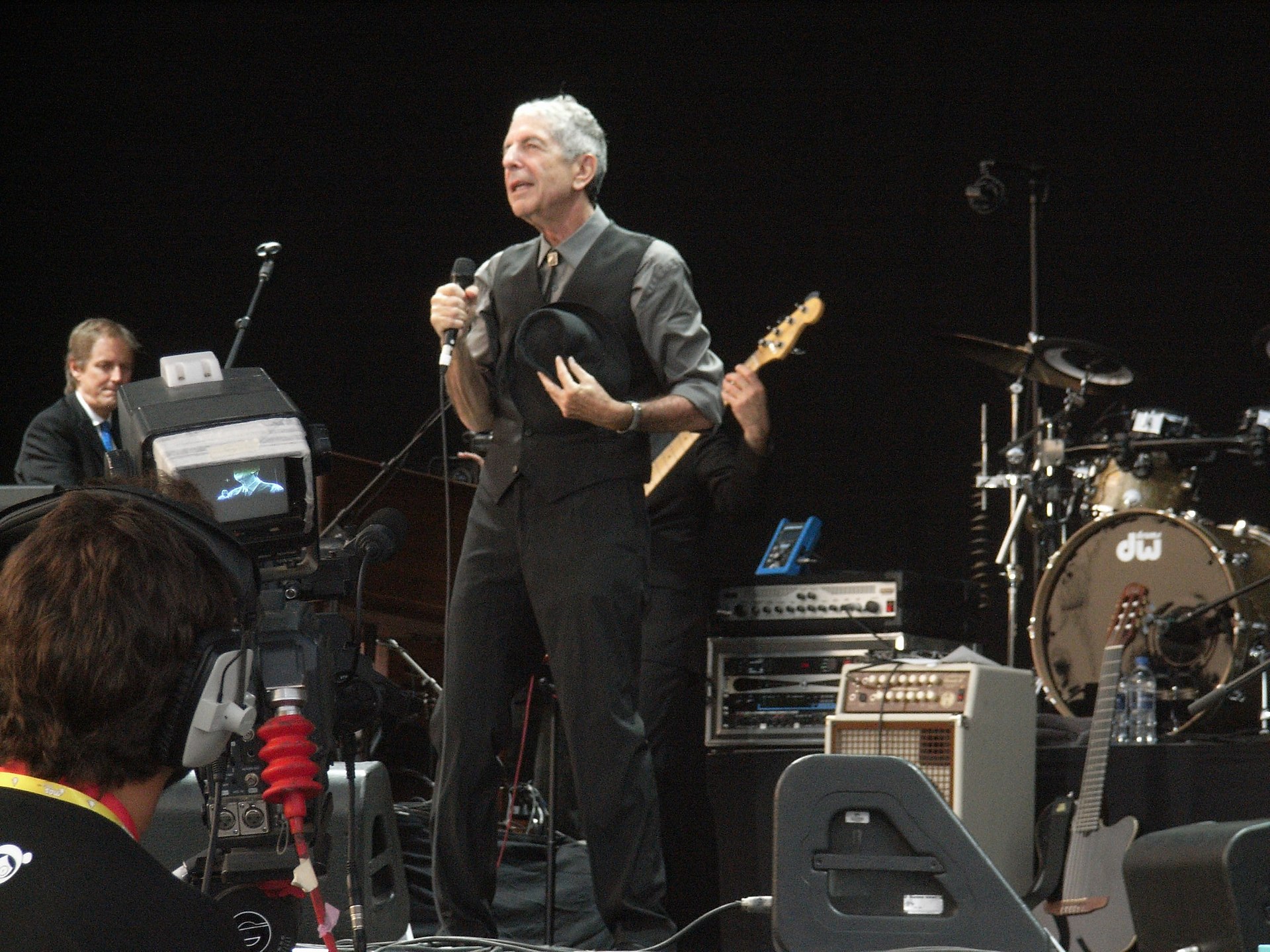

And then the cruellest blow: discovering late in life that his long-time manager had mismanaged and depleted his finances. He was nearly wiped out. Most people would have collapsed under the burden. But Cohen returned to the stage — partly out of necessity, partly out of gratitude that his voice, though changed, could still reach people. Those late tours became legendary: a man in his seventies and eighties bowing to his musicians, singing with generosity, wearing humility like a second suit. He said: “I never thought I would tour again. But now that I have, I don’t want to stop.” From catastrophe came a final creative flowering. Again, the lesson is unmistakable: resilience is not merely endurance; it is the capacity to transform necessity into grace.

Cohen never lost his poetic self. If anything, he grew more himself with each passing year. His lyrics remain some of the finest ever written, not because they are clever but because they are charged with atmosphere and honesty. Famous Blue Raincoat might be the perfect example — a song structured as a letter, so intimate it feels almost intrusive to listen to. The specificity is extraordinary: “the music on Clinton Street,” “so what can I tell you my brother, my killer?” The song never fully explains the triangle it describes, yet it feels complete. Cohen once said the song still troubled him: “I don’t know if it’s a good song or a bad song. It’s just the best I could do.” That is an artist’s truth: you aim for completion, not perfection.

His lyrics, at their best, combine the sacred and the profane, despair and humour, sensuality and transcendence. “There is a crack in everything,” he wrote, “that’s how the light gets in.” The line has become almost aphoristic, but it contains the central belief of his life: brokenness is not the end of meaning; it is its beginning. Over the years I’ve come to love the raw edge of his voice, the sense in which the guitar could fumble a little if it wanted to and not change the essential nature of what is being offered.

And so we return to Hallelujah, the song that has travelled further than any other he wrote. Why does it cross over so powerfully between genres, generations, and contexts? One simple answer to this is because Jeff Buckley ended up singing it like an angel. But the real reason is because it balances the divine and the human with absolute clarity. “Love is not a victory march,” he sings, “it’s a cold and it’s a broken hallelujah.” Few lines better describe adult life: the mixture of hope, fracture, tenderness, wrongdoing, persistence. The song patiently acknowledges the complications of desire, faith, and failure — and yet insists on praising life anyway. It teaches us that dignity is not the absence of wounds but the willingness to continue singing with them.

What we learn from Leonard Cohen, ten years after his death, is that identity and career need not be opposites. He changed direction, but he never changed substance. He moved from page to stage, from monastery to tour bus, from obscurity to acclaim — but always remained a writer first, attentive to words, faithful to craft. He also teaches us to honour the long path: to embrace slow breakthroughs, delayed recognition, and the occasional necessary disappearance.

Above all, he teaches us that artistry is not about being loud, but about being truthful. “I’m not a very good singer,” he once joked, “but I can hold a tune for a long time.” And he did — longer, deeper and more steadily than almost anyone. That long tune, ten years on, is still teaching us how to work, how to endure, and how to pay attention to beauty with the seriousness it deserves.