BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Martin Plantinga

Washington D.C. was never considered a particularly auspicious site for a capital city. For a start, you have to be a fairly unpleasant river to generate your own diseases. The Potomac which runs through the nation’s capital was always considered disease-ridden. Even today, veterinarian manuals tell us all about the symptoms of Potomac horse fever.

Today, the notion of Washington D.C. as being in some way pestilential still percolates in the language: numerous presidential candidates have come here speaking of their intention to ‘drain the swamp’.

To those who lived early on in the Republic, it would have been expected that the capital city would be New York, as indeed it was when George Washington, the first US President, was sworn in.

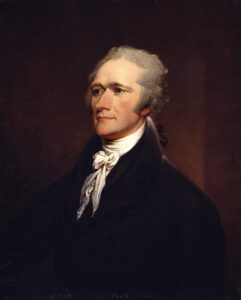

Like so much else at the start of the American journey, the decision to locate the capital in Washington D.C. is attributed to the country’s first Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton was arguably the most gifted of the Founding Fathers and, until Lin-Manuel Miranda got his hands on the subject matter, the least well-known.

In Hamilton, that great opera of our times disguised as a musical, the central song ‘The Room Where It Happens’, shows Hamilton brokering a deal to get his financial plan through Congress by making the capital city of the country Washington and not New York. ‘Wouldn’t you like to work a little closer to home?” James Madison says to Thomas Jefferson. “Actually, I would,” replies the third president.

Now we have, for the second time, the most outsidery president of them all: Donald Trump Jr. The last time I was in town I had a good-ish steak in the then Trump International Hotel just down from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue. The place was full of visiting dignatries: no doubt you wouldn’t want a meeting in the Oval Office to begin on an awkward note if the President of the United States asked where you were staying and you had to give the wrong answer.

Of course, Trump is a New Yorker even more than he is an honorary Floridian. Florida is where he often happens to be: New York is what made him who he is. The same of course was true of Hamilton himself who in all his rambunctious energy, and wild drive, is the archetypal New Yorker.

Perhaps Trump’s win in November 2024 over Kamala Harris might be deemed a sort of reclaiming by New York of Washington itself. Trump, so often caricatured by his millions of detractors as a sort of confederate, is really a Hamiltonian: the author of The Art of the Deal believes in accommodations just like the one Hamilton cut with Jefferson over 200 years ago.

But Trump found during his first tenure that Washington’s inertia isn’t easily undone. That’s because the swamp is an ecosystem: its inhabitants have their own survival instincts. Glad-handing Joe Biden was one of them, and Biden modelled himself to some extent on Lyndon Johnson who, according to his biographer Robert A. Caro, was the Master of the Senate. Johnson understood better than anyone the culture of shady compromises which tends to mark – and mask – modern politics.

It is possible to make a distinction between the sorts of deals Trump excels at and the ones which Johnson used to cut. Trump’s business deals, however crass they can be, usually have a clear outcome: almost always some kind of building. Washington is murkier: you’re never quite sure, to quote Miranda again, ‘how the sausage gets made’. Quite often you’re not sure what the policy is, who really drove it forward, and why it was enacted in the first place. This is from Hamilton again:

We dream of a brand new start

But we dream in the dark for the most part.

That uncertainty regarding what is really going on beneath the surface can easily lead the gullible in the direction of conspiracy theory. Obama wasn’t born in the US. Trump colluded with the Russians. Each is as untrue as the other – and most people in this country at one time believed one of them while at some other point deeming the other patently absurd.

But this doesn’t mean that suspicion about the political classes isn’t sometimes appropriate. It isn’t gullible to be suspicious of something which doesn’t work for you – and it’s that suspicion now which has come to define the American attitude to its politics.

Much has been written about how 2024 was a repudiation of Obamaism – and to the extent that this is true this city has changed. On the surface at least, Washington D.C. is a sort of electoral chameleon which seems to reflect the tenor of the times. The removal men come for the last lot; the next administration come in.

Obama was the most talented politician of his generation; his gifts of eloquence, humour and communication still seem almost spooky. But there’s no use denying it: he was clearly blindsided by Trump’s election victory in 2016. In a sense it was a classic tale of hubris. The 44th President mistook the pull of his charm for popularity at what he actually enacted as president. Once he was no longer on the ticket, the limited appeal of his Party was exposed. Obama is quoted as talking about Trump to his aides after the surprise 2016 win: “I’m trying to place him in American history.” One can hear a bafflement in the reported cadence – a rarity for a man so certain of his gifts.

By 2025, one can begin to see Obama’s presidency more in the rearview mirror – for better and for worse. Was it Obama’s error to view history as something which might conform to his sort of template? It might be a weakness in a writer-president to presuppose narratives like this – and then find that life isn’t a story, but more chaotic than that. Trump, full of what the rapper Kanye West called ‘dragon energy’, was the polar opposite of cerebral Obama, and for that reason Obama didn’t see him coming – and not once, but twice.

At any rate, Trump’s strange zest for politics, his talking to the gut, and his talent for the media cycle, all seem to be preferable for millions of Americans to the intellectualising Democrats.

In 2024, America showed the world that it is allied now more firmly than ever before to the brazenness of Trump if it leads them somewhere different to where Obama, through Biden and Harris, was planning on leading them. It’s as if the electorate were saying: “We’ll take our chances. This looks more fun.” What’s not clear is for how long this will be fun.

It can sometimes seem that the name most uttered here isn’t that of Trump but that of Elon Musk. My suspicion is that it’s Musk, famed for his demonic mode and his epic fallings out, who will cause the 47th President his first problems. Musk is simply too rich to be accountable to anyone – and besides it’s not clear that he cares about people anyway. In Walter Isaacson’s authorised biography he recounts Trump visiting Musk in 2020 in electioneering mode, and saying as he walks into SpaceX: “So who’s for four more years?” As Isaacson recounts it, Musk rolls his eyes and simply ignores him. The time will come when he will do so again.

But even if he doesn’t, the Trump movement is just as vulnerable as the post-Obama Democrats were, to what in business is known as ‘key man risk’. Trump in wildly different ways, is just as much an unusual man as Obama, and will leave just such a gap should he retire in 2028/9 as the Constitution says he ought to do.

But in the meanwhile, Washington D.C. knows that it has witnessed the most remarkable of political comebacks. The Trump Organization sold its Washington property to the CGI Merchant Group in 2022: it felt symbolic at the time, a sort of strategic retreat. Nevertheless it probably netted him around £100 million in profit. We now know a little more about Trump’s resilience than we did in 2020: perennially underestimated, he knows how to make money, just as much as he knows how to manipulate the media. Nobody on the left foresaw that the Twitter ban would lead to Truth Social – not least because they can’t see Trump’s appeal to his supporters.

Nevertheless, Washington D.C. is never going to be Trump country. 90 per cent of the District of Columbia voted for Kamala Harris in 2024. It remains a city of erroneous chatter and strained gossip, all carried on in the Dupont, and in Oyamel Cocina Mexicana, where punters hope to catch a glimpse of Obama eating at his favourite restaurant.

Londoners tend to feel at home in Washington. Its great buildings have that imperial look which we see in the National Gallery and the British Museum. This is borrowed from Rome, and Rome in turn borrowed it from Ancient Greece. It is a place of Corinthian pillars, and imposing façades: it can seem so sure of itself as to its external appearances, yet as time has gone by, some seasoned observers are coming to suspect a certain fragility to it all. The plaster is cracking.

That’s partly due to 6th January 2021 of course – a bad day for American democracy, when Trump, at his petulant worst, did all he could to prevent the certification of Biden’s victory. It is an astonishing fact that 6th January 2021 didn’t destroy the career of Donald J. Trump Jr.

In fact, 2024 arguably shows how little America cares about American democracy if it doesn’t deliver improvements in their own lives. We now know for sure what we suspected in 2016: there is another America out there in the small towns and in suburban areas which not only dislikes Washington D.C. but actively loathes it.

Why did Trump manage to ride out January 6th? One possible explanation is that people are beginning to wonder whether the Union has definitely turned out to be a good thing. Over the years I’ve begun to wonder whether Washington D.C. has some sort of falsity in it: the Union is something hallowed to Americans but it is certainly an unwieldy coalition. It is hard to think, for instance, of a single thing which Gavin Newsom’s experiments in California have in common with, say, the Florida of Ron De Santis. Heavily centralised government leads to great concentration of power, and this in turn can create the refusal, or inability, to address local issues – and even in many instances to even know what those issues might be.

We quite often think of local issues as being of no importance: they are, in our current parlance, of lesser importance than the national interest, and even than the direction of the species globally. Yet most of us visit and revisit the same parts of our local environment. If the money isn’t there from the centre to help make them better, things sour quickly.

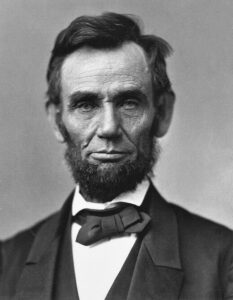

In America, at the centre of this argument, is the immensely mysterious figure of Abraham Lincoln. The city leads you by a process of time-travelling logic from the Hill, down past the Washington Monument to the Lincoln monument.

Lincoln is without question one of the strangest men ever to live. He is one of the few people I can think of who Trump hasn’t been rude about – and Obama of course reveres him. He said many wonderful and wise things, but presided over extraordinary carnage. His public persona is loveable, and nobody is any doubt about his brilliance as a politician who knew all about timing.

I have always loved his speeches, especially the Second Inaugural Address, though I have also often found his anecdotes and prairie jokes somewhat tedious. His decision to emancipate the slaves was an act of statesmanship which isn’t easily matched in the annals of political history – and yet I am never sure of his motives for anything. A deep sadness was lined on his face, and it coursed through his being. There never seems to be a decent reason for it. Something ailed him.

A deep study of Lincoln’s life and speeches can lead you to surprising conclusions.

All the evidence is that Lincoln’s motivation to end slavery sprang from his love for the Union, and yet what is never stated is why he loved the Union so much. We think of the Union as an inevitable thing, but it could easily been otherwise had Lincoln reacted differently to secession. It is easy, for instance, to imagine the American continent as a number of states living in harmony where slavery had been ended over time in the south without the need for the civil war which Lincoln insisted upon.

If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone I would also do that.

There is something chilling about the logic of Lincoln’s words. Furthermore, it’s clear that by 2025 we have failed to get government by the people, for the people and of the people as Lincoln envisaged at Gettysburg: what we have is a system which works to such a limited extent that people will vote for a narcissist like Trump in the hope he might change, in preference to the highly centralised and stagnant status quo which was the inevitable result of Lincoln’s decisions. If on some fundamental level Americans have turned against America – this country which is, according to surveys of its people perennially on the wrong tack – then we must also understand that they have turned against Lincoln’s America. Yet Lincoln remains their saint.

Saint or not, the simple fact is that around 620,000 people died during the Civil War, and Lincoln was absolutely clear that they didn’t die for slavery but for the Union. That is to say that they died for an abstraction which he was always very careful not to go into too much detail about.

So why was Lincoln so keen on the Union? The frightening answer which comes out of the silence is: “Because it made him President and kept him there.” Without the Union, he would have been President of a lesser nation and I don’t know that this would have matched the ego which one sometimes sees lurking underneath the folksy persona.

“I am the President of the United States, clothed with immense power, and I expect you to procure those votes,” he is meant to have said to Congressman James Alley when it came to securing the 13th amendment, which would forbid chattel slavery.

Alley recalled it 23 years later but ever since Steven Spielberg had Daniel Day Lewis say it so memorably in his film Lincoln (2012), it has been an uncomfortable moment for Lincoln lovers. Naturally, there has been a desire to claim that he never said it, or that he said it differently. But what if he said it? What if, deep down, he was like that?

It is a big question for any American to face. This is why the real Lincoln hardly gets a look in in Washington D.C. Instead we have a presiding saint and buildings which keep the tourists coming. There are fine art collections, important-looking buildings, and of course the White House.

It’s rare in the US to find churches of any particular interest but across from 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue, you find St John’s Lafayette Square. It has a fine gospel choir and at the back a pew which Lincoln is meant to have come and sat down in during the Civil War.

We’ll never know what really animated Lincoln deep down, how he would have felt when he came to pray here, if he prayed at all. History is essentially psychological. It matters hugely what our presidents are like internally: the meaning and intent of actions is more important than anything. Furthermore, as we change, our perception of history changes too: my sense is that Trump, despite his appalling flaws, is a far more consequential figure than Obama since he marks America’s move away from Lincoln’s America towards a more fluid, chaotic, and hopefully energetic nation.

It was this which made the Trump assassination attempts, especially the first one., so significant. It humanised Trump, as well as showing his courage. But it was more than that: it made voters think he might yet be a better man, and undergo some kind of transformation – or metanoia, as the Greeks called it. They felt this at the same time as knowing that he could articulate their concerns, however goofily, far better than Harris, Biden and Obama.

The decline of the power of Obama is far from certain: nobody should underestimate his gifts of persuasion and rhetoric. The extent to which his wife is an asset has also grown over the years: Michelle is often deemed more popular even than Barack.

But something has shifted irrevocably in this country – and what’s perhaps most notable is that Washington doesn’t seem to know it yet.

Biden and Obama both won around 92 per cent of the vote there: results which would gratify Vladimir Putin. Either Washington D.C. is sorely mistaken about the nation it is meant to be governing, or else it is in possession of some sort of absolute truth which it isn’t effectively communicating yet to the other 49 states.

This unruly and questing energy simmering beneath the surface of imperial structures has its origins in history. The first to arrive here were enterprising seekers, prepared to imagine another life for themselves – a new frontier. That spirit persisted enough to create an original nation, ruled from the centre. Ever since the main question has been: how loose and free is central government to be?

Hamilton’s answer to the question hinged on the fact that the nation was also born in debt: it would require a strong Treasury in order to get the nation into credit and to secure its long-term future – a future which turned out to be Lincolnian.

And is our future now therefore Trumpian? All that depends on the strength of the Lincoln legacy, however much it might seem to fraying. In one sense it’s personal, to do with a myth – just as Britain’s contemporary sense of itself rests on the Churchill myth. Everything in this country keeps coming back to Lincoln, that strange man who spoke so cryptically, and occasionally beautifully. It doesn’t matter that he was a far more inept war leader than is usually taught in school – what matters is that his myth at a certain point in time, and partly due to the circumstances of his death, was accepted by the vast majority. The more you study him the more you realise that Lincoln worship has in some way stagnated the country because it prevents us from seeing the Union and slavery as different things.

They inhabit different categories. Slavery is for most of us a clear moral question to do with personal freedom. When it is financial or to do with employment it is, we hope, easy enough to point out and therefore to eradicate. It might even be worth fighting a war for – though even there I would prefer the William Wilberforce route to Lincoln’s. The underestimated British Prime Minister Theresa May has made modern slavery her most important cause. She could hardly have found a better one.

But the Union simply isn’t of this nature: its proper place is in political philosophy and in notions of good and bad government. It is an institutional question and it is possible to imagine a highly centralised government full of superb and caring officials who did a good job for their citizens. It is possible to imagine a less centralised government doing the same: it would depend on individual motivation.

Slavery is not like that to the same extent. If we take somebody’s freedom we do something very fundamentally evil to that person.

What happened was that two different kinds of questions became conflated: the political structures of the country and the moral evil of slavery. Historical circumstance did this, in that the two questions were live at the same time; it was up to Lincoln to unpick them, but he ended up yoking them together as intertwining aspects of his own myth.

It was a brilliant balancing act. He was able to state that he was primarily motivated by the Union question, while simultaneously hinting that it was all to do with the slavery question really in his heart of hearts.

Conversely, when he emancipated the slaves, he was able to say at the same time that he was doing it primarily to win the war.

Quite likely, like every other politician, he just wanted to be President. When that was achieved, he wanted to be President of the most powerful country within his grasp. Having done that he wanted to go down in history as the best President of that country, by also saying some memorable things. He was unusually gifted and so he did all that.

But what are we left with? America was built on the ambition of a few men talented enough to enact their dreams. The American dream which they bequeathed has now become unobtainable for many since power became concentrated, and to add insult to injury, slavery never entirely went away.

Will Trump change this? It is quite possible that he is a sort of bizarre John the Baptist figure sent to loosen structures and that some later President, less weird than he is, will pick up his political project and really give new life to this exhausted land. Trump certainly won’t be the President we need him to be without some internal shift: he would need one feels to become rapidly kinder and wiser.

My sense is that he likes power just as much as all his predecessors, though I sometimes think he sees its silliness a little better than many of them. It isn’t much to cling to, but this vast cacophonous country has a curious way of enduring.