BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

There’s nothing quite like a global pandemic to make people across society rethink their priorities writes George Achebe

Simon Ferrar knows exactly where he’ll be buried: he’s ear-marked a plot worth £4,500 under some rather splendid blackberry bushes in Surrey Hills. ‘As in life, it’s location, location, location,’ he jokes, looking at one of the premier positions in the cemetery.

Except this is no conventional cemetery, and Ferrar will also die knowing that he has been responsible for the burial circumstances of some 28,000 around him. He’s the founder of Clandon Wood, a natural burial ground, and a part shareholder in it as well. ‘I created a nature reserve because we were looking to encourage a huge diversity of wildlife here. We wanted to add another little corner of the natural landscape to the Surrey countryside,’ he says.

The funeral business is, of course, recession-proof and has even been helped by the pandemic. Natural burial involves graves made from biodegradable materials; each plot is three-feet deep and involves no vertical memorial. Ferrar explains another difference: ‘What’s unique is that we set up a trust fund. Every single person who purchases a plot here pays a one-off fee of £250 which goes into the trust. By the time we’ve sold all 28,000 plots, that trust fund will be worth in excess of £7 million.’

We drive out in a golf cart into the plots. Some of the graves look like large scratches in the earth. In other instances, one’s memorial is simply a tree, or some wild grass. He gestures at a plot. ‘Over there, there are buried two twins. One killed himself jumping off a building, and the other couldn’t live with it. Three years later his brother killed himself too.’

But the funeral, he says, was meaningful. ‘The mother said they weren’t meant to live long lives.’ He adds: ‘We care for the living here as well as the dead.’

A Morbid Culture

When the pandemic struck, it found a morbid culture. Ours is an odd, almost sanitized plague, so unlike the Renaissance and medieval counterparts: when the deaths rack up, they do so behind closed doors. We don’t see them for ourselves. And this fact has created communal space with which to discuss another crisis: our mental health.

Ferrar views his business as a ‘throwback to a couple of centuries ago where families can take the coffin on a handcart. We’ve been burying people on this island for about 30,000 years. It’s only in the last few hundred years, we’ve got used to the kind of Victorian funerals, the moralization and the grimness of that.’

At a time when our former structures have been removed, and we experience uncertainty as to whether our life shall return to anything like ‘normal’, Ferrar’s project can teach us perspective. As the world quietens, many have found that they had become disconnected from the real cycle of nature.

The £65K Club

It isn’t difficult to understand why some who have lost their jobs, or who have had their weddings placed on hold, or found themselves subject to domestic abuse, might be struggling at the present time.

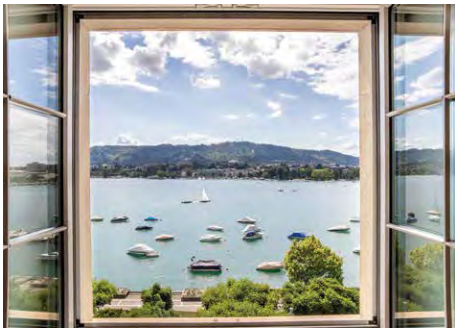

It’s harder to explain why mental health has become such a problem for FTSE250 CEOs and the superrich. But according to Marta Ra, the founder of Switzerland based clinic Paracelsus, which also has a UK branch and charges £65,000 a week, that’s exactly what has happened. ‘There’s this unconscious bias that the very wealthy are always happy. But actually, they’re often sadder than people with less financial strain,’ she says.

For some this will be a dubious sob story – and yet it tells us something too about who we are.

‘All individuals have their own private fears and problems,’ Ra explains. ‘Perhaps they worry for their employees, or the fate of their companies. And so they start turning to substance abuse. Or maybe they only did social drinking before, but now they start to drink heavily. And locked down with their spouse and children, they’re just as likely as anyone to think: “Who have I married? I can’t handle this.”’

It would seem that at a certain point the noise of life became so great – and what the Victorians called ‘the Battle of Life’ (the title of a Charles Dickens novella) became more intense. Sometimes one senses that the virus has been specifically designed to make us look again at who we are – at where we’re going.

Ra explains: ‘People who are stuck at home have to face themselves for the first time, and really face themselves.’ She adds: ‘Our society wasn’t functioning to be in the present.’

The depths of the forest

But what about those people who are trying to help us with our mental health? Before the crisis, buzz words like ‘mindfulness’ and ‘wellness’ had become ubiquitous, and when I meet Ferrar, I am struck by his laid-back intelligence. His is the sort of spiritual calm which the frenetic Londoners among us tend to envy.

Across from Clandon Wood, tucked away behind postcard-idyllic Shere, is the Forest Bathing Institute [FBI]. In May 2019 Dame Judi Dench became a patron of the organization, but it’s been more broadly on the rise.

I ask Gary Evans, CEO of FBI to explain its origins: ‘”Forest bathing” is actually a translation from the Japanese shinrin-yoku.’ he explains. ‘In Japan in the 1980s, the Japanese government decided they wanted to get people out of big towns and into nature.’ But this wasn’t some hippie whim: it was driven by hard science.

They were researching the health benefits of nature and woodland. When they looked at blood, they found improvements in the immune system. A prolonged exposure to nature caused blood pressure to come down in people who had high pressure, and caused those with low pressure to experience a normalization.’

Intrigued, I head to Surrey to meet with Kate Robinson who takes me into the woods near Newlands Corner.

Over the course of a few hours, I am asked to focus on the shapes of the trees, to explore the smells, to play with leaf litter, to share my thoughts of the forest, and to listen closely to the breeze playing in the upper canopies. The session finishes with a meditation. For a few days afterwards, I find that the wood seems to exist alongside me, in a way which it wouldn’t if I had taken a long walk.

I recall the words of Marta Ra: ‘You can be a billionaire at 23 and still feel fear and loneliness – and the uncertainty of the virus only adds to that fear.’

And perhaps there is something especially apt about all this. Coronavirus, after all, took us by surprise out of the wet markets in Wuhan, where to paraphrase Oscar Wilde, the unspeakable went into pursuit of the uneatable – and duly ate them. As Green peer, and former Green Party leader, Natalie Bennett recently told me: ‘The economy is a subset of an environment. There are no jobs on a dead planet.’ Perhaps part of our duty now is to think again about what surrounds us. And it might after all be that the right job revelation lies just as much on a long walk, as it does on LinkedIn.

Drawing Together

And yet, for some, that will seem too solitary. Others have sought their own reckoning by looking in new and exciting ways at community.

Sally Shaw at First Site gallery in Colchester had been busy in the run-up to Covid-19 with, among other things, a landmark exhibition with Anthony Gormley. Once the virus struck, she realized she had to do something to benefit the local community. ‘The NHS approached me during lockdown. They said: “We’re worried about the virus, yes, but the next thing we’re worried about is the mental health fallout for our staff and also those directly affected by Covid-19”.’

But that assessment proved to be the tip of the iceberg. Shaw lists the challenges: ‘Of course, they were also worried about the stress the pandemic will cause through mass unemployment, emotional pressure and not being able to grieve properly.’

Shaw thought of a way to help. The gallery is part of the Arts Council collection, which consists of 7,000 works collected over 75 years; it’s been built up with the national legacy in mind. Shaw continues: ‘We thought what we might do is invite people to interact with that collection and pick works which represent their experiences and, with a light touch, introduce talking therapies to people’s worlds.’

The gallery introduced a private part of the website where NHS staff in the region and care home workers can submit their stories to the portal. Shaw now plans to find ten distinct stories which will comprise a spectrum of experiences to ‘enable us to create a narrative around the different types of effects on people’s lives.’ The goal, she says, is to create a ‘creative conversation which may be an exhibition at some point.’

That sense of community is also evident at Clandon Wood where Ferrar regularly hosts theatrical performances. ‘We have things like Music in the Meadows where I invite local musicians down, and people bring a picnic. We had four Alan Bennett plays last year, and we had Shakespeare in the Meadow too. Then we have meditation mornings plus all the other events that we have to support grieving families.’

The Forest Bathing Institute too is looking at children’s days, in part designed to help take the burden off local parents, and give children experiences valuable to them going forwards.

It is an image of another life – one that would have felt impossible six months ago. We inhabit for the time being a world slower, quieter and in some ways smaller – but also one with the potential to be richer and deeper than what we had before. It’s a world where time and nature feel like more precious commodities than ever before. It’s also a period when money might matter less because our mortality has been vividly illustrated to us: we all lose our possessions in the end. Ferrar explains to me that a team of archaeologists found evidence of Bronze Age occupation at Clandon Wood. ‘We talk of possession, but the land is only ever held in trust,’ he says, as we pass another unmarked grave.

The curious thing is that this fact, which might make us despair, turns out to be a beginning of happiness. Mental health begins in being rooted in the facts. The virus, awful though it has been, has reminded us how transient we are, but in doing so thrust us back on ourselves, and forced us to renew.