BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

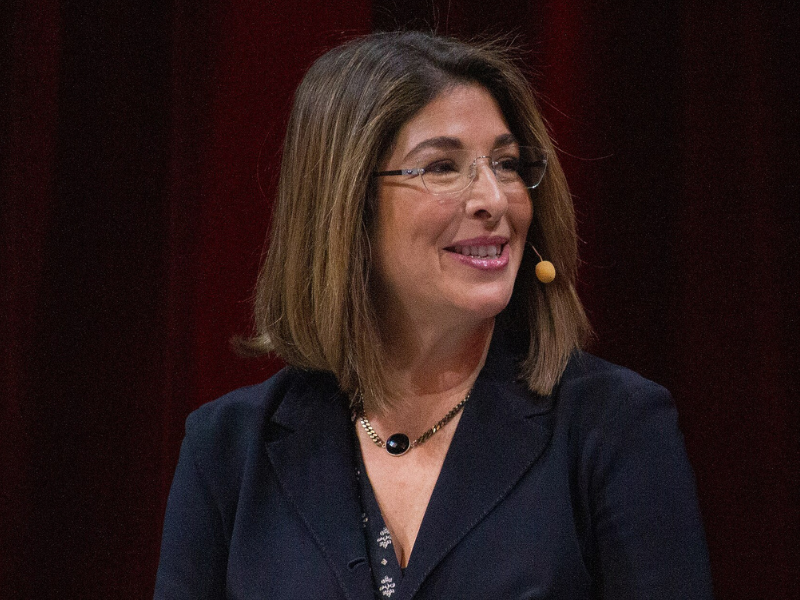

Naomi Klein

It’s hard to overstate the weirdness of watching an idea go from laughable to inevitable. When I published No Logo in 2000, the idea that an ordinary person could or should become a brand was something we laughed at. At the time, personal branding was mostly reserved for celebrities – Michael Jordan could be a brand, maybe Richard Branson – but for the rest of us, it sounded absurd. Who had the time, the team, the resources? What would it even mean?

But then came the iPhone. Then Facebook. Then Twitter. And suddenly, we all had ad agencies in our pockets. Social media handed us tools that had previously been the exclusive domain of corporations and marketing firms. They were “free,” we were told. But of course, nothing is ever really free. These tools began to shape us in their image.

What followed was more than just a technological shift – it was the logic of the corporation entering the soul. The rigid disciplines of branding – consistency, repetition, simplicity, and emotional clarity – migrated from the domain of sneakers and soda to the terrain of selfhood. And that shift has changed not just how we present ourselves, but how we organise, how we resist, how we dream. When I look back at No Logo, it was an attempt to understand the rise of lifestyle branding and the early stages of global consumer culture. It emerged from a moment when travel was becoming eerily homogenised – when you could land in any airport in the world and hear the same song playing, buy the same products, eat the same food. It was a warning about the creeping sameness, about the way branding flattens difference. But what I didn’t fully grasp back then was how quickly that flattening would fold inward.

Now, a generation later, we see something even more intimate: not just global homogenisation, but internal homogenisation. We are encouraged – no, expected – to distil ourselves into fixed, static icons. Like Coca-Cola or Apple, our personal brands must be instantly legible, unchanging, digestible. We must be on-message. We must perform well.

And yet, none of this really was inevitable.

The rise of personal branding didn’t happen in a vacuum. It emerged out of economic desperation. It came on the heels of outsourcing, of mass layoffs, of the dismantling of stable employment. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, corporations restructured themselves to be leaner, more flexible. They sold off physical assets, fired full-time workers, and replaced them with contractors and temp staff. The old promises – of pensions, of lifelong careers – were broken.

In this context, personal branding wasn’t just a novelty; it was a survival strategy. “Don’t worry,” management consultants chirped, “you can be your own brand!” You didn’t need a job – you just needed hustle. It was the gig economy’s founding myth: reinvention through performance. And to be clear, this wasn’t about self-expression. This was about monetisation. It was never really about authenticity. It was about survival.

That’s the part that often gets left out when we talk about influencers or streamers or online creators. We frame them as self-made digital entrepreneurs, avatars of empowerment. But when I talk to my students – many of whom are actively engaged in this world—I hear a different story. They aren’t building brands because they want to; they’re doing it because they feel like it’s the only viable path to stability. They’re performing not because they’re free, but because they’re afraid.

And this logic hasn’t only colonised individuals. It’s reshaped our movements.

When No Logo came out, the anti-globalisation movement was just beginning to crest. The Seattle WTO protests, the mobilisations in Genoa – these were organic eruptions against corporate rule. And because I had just written a book on anti-corporate resistance, I was suddenly thrust into the spotlight, asked to speak for a movement I hadn’t organised, hadn’t built, and wasn’t elected to represent. It felt awkward then, and even more so now, because there were no mechanisms of accountability. I was just a person who had written a book. But the media needed a face, and I was convenient.

Today, that process is even more exaggerated. The structure of social media means that visibility becomes power. The people with the biggest followings become the presumed leaders—regardless of their organising work or their relationship to the community. A movement can be reduced to a hashtag. Organising becomes branding. And collective action begins to resemble influencer marketing.

This isn’t to say that these platforms can’t be used strategically, or that visibility is inherently bad. But when our movements start to mimic the very logic they were meant to challenge, we have to pause. We have to ask: what are we replicating? What are we internalising?

Because at its core, branding is about sameness. It’s about stability. A good brand doesn’t change too much. It stays familiar, repeatable. But humans are not brands. We grow, we contradict ourselves, we make mistakes. Real solidarity – real politics – requires the space to be messy, to be wrong, to change. But when we are all busy curating and controlling our image, how much room is left for actual transformation?

What frightens me most is how totalising this logic has become. Even oppositional movements, even anti-capitalist projects, can become mirrors of the system they fight. We brand ourselves against branding. We sell resistance. We trade in radical aesthetics while the underlying economic structures remain untouched.

And yet, I don’t think the answer is a retreat into nostalgia. We can’t go back to some imagined golden age of organising. But we can interrogate the terms of our engagement. We can ask harder questions about the infrastructure we rely on. We can be more conscious of the ways in which corporate logic infiltrates our thinking, our movements, our sense of self.

Ultimately, Doppelganger – my most recent book – is in many ways a return to these same questions, but from a different angle. It explores what happens when identity is consumed by distortion, when we see ourselves split and refracted through the funhouse mirror of digital life. If No Logo was about the rise of branding, Doppelganger is about the psychic toll of living inside the brand.

We are, I think, in a fin de siècle moment – a time when one world is ending but the next has not yet emerged. The branding of the self, the algorithmic shaping of the public sphere, the monetisation of personality – it all feels untenable. And yet, we don’t yet know what comes next.

What I hope for, in this liminal space, is a return to a different kind of knowing. A politics that isn’t driven by spectacle, but by substance. A self that isn’t flattened for profit, but expansive in its contradictions. A movement that doesn’t seek to go viral, but to go deep.

We may not be able to un-invent the technologies that turned us all into brands. But we can reclaim our humanity from their grip. And that, I believe, begins with remembering: we are not products. We are people.