BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson

A while ago I wrote a book about Roger Federer. During my researches, I recalled a story of a friend of my father’s. This was Mike Eaton, who had been a formidable tennis player in his day, playing Junior Wimbledon. He subsequently fathered a son, Chris Eaton.

Chris, as some readers might remember, had an impressive run to the second round of Wimbledon in 2008. Chris was one of those players, a sort of early male prototype of Emma Raducanu, who relished the big occasion. He didn’t win his second round match that year against Dmitri Tursonov, the then 25th seed, but it was close for a while: “the Eaton rifle” as he had once been known at school lost 6-7, 2-6, 4-6.

Chris reached a career high singles ranking of 317. Thinking back to 2008, in retrospect Eaton was never likely to take a set off Tursonov. But if Tursonov had any temptation to gloat about it, it was swiftly removed: he lost in the next round to Janko Tipsarević. And Tipsarević at that time, as he would now admit, wasn’t realistically in the position of taking a set off any of the likely winners – then, as now, one of Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal and Novak Djokovic.

The Raducanu rise means that tennis continues to be a pretty reliable bet for any young person thinking of entering sport

Why do I bring this up? It’s because of a simple fact that Eaton’s father once relaid to me. Namely, that he had never once managed to return a single serve of his son’s. Let’s remember that Mike was a brilliant player in his own right. And let’s remember how easily Chris was dispatched from Wimbledon.

In a story like this we begin to gauge the sheer level which the best players are at. Most of us don’t need a reason to feel more admiration for the so-called Big Three: we feel it already. But it is sometimes difficult to know quite how good they are. The story of the Eaton family tells us.

The continued popularity of tennis seems assured, even though there must soon come a time when Federer and Nadal must retire, their bodies finally succumbing to decades on the tour. Djokovic will likely following suit in time, and surely will be the most gilded player of them all when he does so.

The success of the game hasn’t always seemed as certain as all that. I am old enough to remember the big serving nadir of men’s tennis in the early 1990s when people like Michael Stich and Richard Krajicek could win Wimbledon seemingly while possessing one shot. I remember the 1991 final, between Stich and an ageing Boris Becker, as an unwatchable fiesta of boredom, where one wondered whether equipment had begun to chip away at skill: the battle went to the biggest serving, which really meant it kept going to the tallest.

It was part of the magnitude of Federer’s achievement to change that, more or less on his own. People forget that in 2003, we felt excitement at the brilliance of his play – but also relief that we were now allowed to watch rallies again. And though Nadal and Djokovic both brought different styles to the game, they eventually learned to beat Federer on terms of Federer’s own making. It’s probably this which makes Federer fans so ardent: they remember what went before.

Looking ahead, there is a natural trepidation about any era where Federer, Nadal and Djokovic aren’t playing anymore. But if anyone had any doubts about the future of tennis: enter Emma Raducanu.

Raducanu’s success remains the most extraordinary story – and may even have been made more so by her subsequent decline in form, which I’m willing to bet, has nothing to do with core motivation, but all to do with her inherent instinct for the big occasion. The real test of Raducanu won’t be how she does in Transylvania but how she does in Melbourne in early 2022. After the dizzying heights of her US Open victory, it may take Wimbledon to get her fully motivated again.

The Raducanu rise means that tennis continues to be a pretty reliable bet for any young person looking to enter sport. Of course, nowadays, with prize money as it is, you can earn a decent living as a player even without lifting many trophies. To take a random example, the current world number 99 Henri Laaksonen – not a player I had heard of until Google turfed him up – has career earnings in prize money alone of $1,849,304. That approaches financial security. To put this into perspective, it surpasses the earnings of one of the true greats of the game Rod Laver, who is estimated to have earned around $1,500,000 in the 1960s.

So the money keeps pouring into this most gladiatorial of sports: and some of it trickles down into other career options. Some of these are advertised on the Lawn Tennis Association website which has a helpful Live Vacancies tab. A Tennis Relations and Events Manager at the National Tennis Centre can command £45,000 pa plus, although the ads also stipulate that you need to be at the office in Roehampton three days a week. The job is seeking candidates who will “provide and implement strategic event development opportunities across our Events business and support with the delivery of our Athlete Plan.”

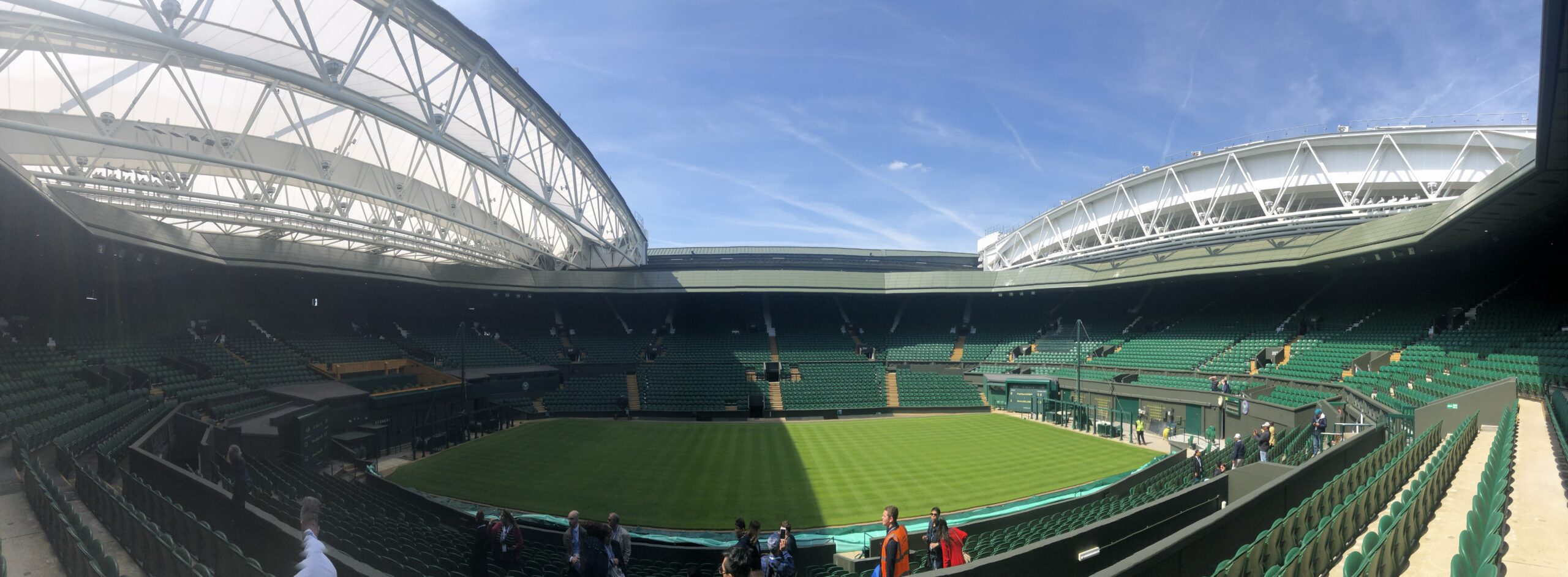

Other jobs abound on the web. There is an ad for a seasonal gardener at Wimbledon – an idyllic-sounding job if, like me, you feel that Wimbledon fortnight is somehow elevated above all the other fortnights the calendar year has to offer. This is advertised as a “flexible role across the whole Horticultural Department’ and in the ad at least sounds like a great opportunity to see how those lawns look so immaculate year in, year out – and join a dedicated team to boot.

Sometimes, there are also marketing initiatives which need staffing. The LTA’s current project is called “Tennis Opened Up” and its mission is to make tennis Relevant, Accessible, Welcoming and Enjoyable.”

There is just a hint here that tennis has fallen behind other sports – most notably football – in terms of appealing to those outside the fee-paying school system. But it also means that more and more, having taken part in Wimbledon fortnight isn’t necessary in order to have a fulfilling career in the sport.

Of course, as with every sport today there are a range of careers which touch on tennis: from sports agent to sports journalist and sports PR and sports charity, the major sports now touch every area of life. At Finito we have mentors with sports specialty and welcome all candidates seeking a career in the sector.

And Eaton? That’s easy, he now works as a tennis coach. He joined the Wake Forest men’s tennis staff as an assistant coach during the 2016-17 season before being elevated to associate head coach prior to the 2018-19 season. When I last saw his father, he still hadn’t returned one of his son’s serves.