BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

George Achebe

There are no cathedrals left to build. This is the quiet knowledge that hums beneath the profession of architecture in our time. The days of Brunelleschi and Borromini, when an architect could spend a lifetime lifting stone to the heavens in the service of transcendence, are gone. Today’s work is different—more bounded, more briefed, more bureaucratised. And yet: there are those who persist in finding sublimity within the commission. Who, in spite of everything, still manage to make architecture do what it has always done at its best: remind us who we are.

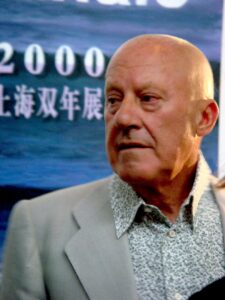

Norman Foster turns 90 this year. He is not just one of Britain’s most successful architects; he is the consummate 21st-century builder: international, collaborative, technologically attuned, and never once interested in the kind of starchitecture that reduces the building to a signature and the city to a sketchpad. His is a practice not of bombast but of clarity. And that makes him, in some ways, the last great modernist.

To speak of Foster is not to speak of one building, or even of many. It is to speak of a way of working, and—more importantly—a way of thinking. Foster’s buildings are often described as clean, minimal, restrained. But in truth they are generous. They believe in the future, and they place human beings at the heart of that belief. That’s why so many are places of work, of assembly, of movement. They are never precious. They are used.

He has always been interested in what it means to work—not just as an architect, but as a citizen. Look at the Reichstag in Berlin. That now-famous dome of glass doesn’t just let in light; it makes visible the workings of power. The visitor spirals up, the parliament sits below—an architectural metaphor rendered legible to all. Germany, so often a land scarred by the 20th century, found in that gesture a reassertion of democratic dignity. And Foster, for his part, found a symbol not of his own ego, but of restoration.

Germany, Berlin – Reichstag

He has long had a particular relationship with Germany. His office has employed many of its brightest young architects, and he is held in high regard not only for the Reichstag but for his sense of order and clarity—qualities deeply admired in a culture that still reveres engineering as a poetic discipline. But Foster is not national. He is global in the truest sense: a student of the built world who sees in each site an opportunity not to impress, but to elevate.

The Commerzbank Tower in Frankfurt, completed in the 1990s, was the world’s first ecological skyscraper. Not because it sought the label—this was long before the age of LEED certification and ESG metrics—but because it was designed to breathe. With its atria and gardens spiralling up through the structure, it was a provocation in steel and glass: could even a financial tower have soul?

Commerzbank Tower, Frankfurt

It turns out it could. And that has been Foster’s gift: to find, amid the constraints of budget, legislation, and use-case, the flicker of the transcendent. That’s not easy. Today’s architects are hemmed in by regulation, by planning committees, by clients who want more and pay less. The work is rarely about vision alone. It’s about compromise, iteration, and endurance.

But in that world, Foster has managed to do what few have done: create a language that is instantly recognisable without ever being self-indulgent. The Gherkin—30 St Mary Axe—is a perfect example. It is often spoken of as iconic, but it is really pragmatic: shaped as it is to withstand wind loads, to minimise light loss to the street, to require less air conditioning. It is a building that teaches you, if you listen, that beauty is a by-product of intelligence.

30 St Mary Axe, ‘The Gherkin’

This, too, is Foster’s genius: his intelligence is technical, not theatrical. He has always been an architect of the real. And that is no small thing in a profession often tempted by spectacle. The reality of architecture today is not of lone visionaries but of teams. Foster’s firm employs hundreds—designers, researchers, engineers, model-makers. His research studio doesn’t just test materials; it models futures. It asks how cities will move, how buildings will age, how energy will flow. And it does this not in the hope of being noticed, but in the hope of being useful.

That word—useful—is rarely associated with art. But it should be. Particularly in architecture. Buildings are not sculptures. They must serve, support, sustain. And Foster’s do. They do not just gleam. They function.

His work at Apple Park in Cupertino is testament to that. Commissioned by the late Steve Jobs and built after his death, the building is a circle: vast, inward, quiet. It is a campus not of dominance but of meditation. Trees in its core, solar panels on its roof, silence in its design. It could have been a monument. Instead, it is a working environment—albeit one that redefines what a working environment can be.

Apple Park

And what of employability? That often-ignored measure of architectural success? Foster has created not just buildings but jobs. His practice has trained thousands. It has become a proving ground for the best talent from every continent. He has shown that architecture, when properly run, is not only sustainable environmentally, but economically. It is a career, not a calling. A practice, not a fantasy.

This is vital. Too many young architects emerge from university with vision but no footing. Foster’s legacy is not only in glass and steel—it is in the architects he has sent into the world: rigorous, well-trained, realistic, yet still capable of dreaming. And in this, too, he echoes a truth larger than architecture: that the highest form of vision is that which includes others.

Turning 90 is, for most of us, a slowing. But Foster shows no sign of stopping. He is still sketching, still questioning, still listening. His firm continues to work across every continent. It advises on city planning, on energy systems, on new ways to live. For Foster, architecture is not the creation of forms but of futures. It is not about fame, but about continuity. It is about the quiet thrill of making something that works.

And perhaps, in the end, that’s what separates him from so many of his contemporaries. He has never chased eccentricity. He has chased excellence. He has not sought to disrupt, but to clarify. And in that clarity lies something radical.

We may live in an age without cathedrals. But if architecture still has a sacred task, it is this: to make the world more liveable. To create spaces where work can happen, where life can unfold, where democracy can be seen, and where beauty has a chance to emerge.

Foster has done that. For ninety years, and counting.