BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson

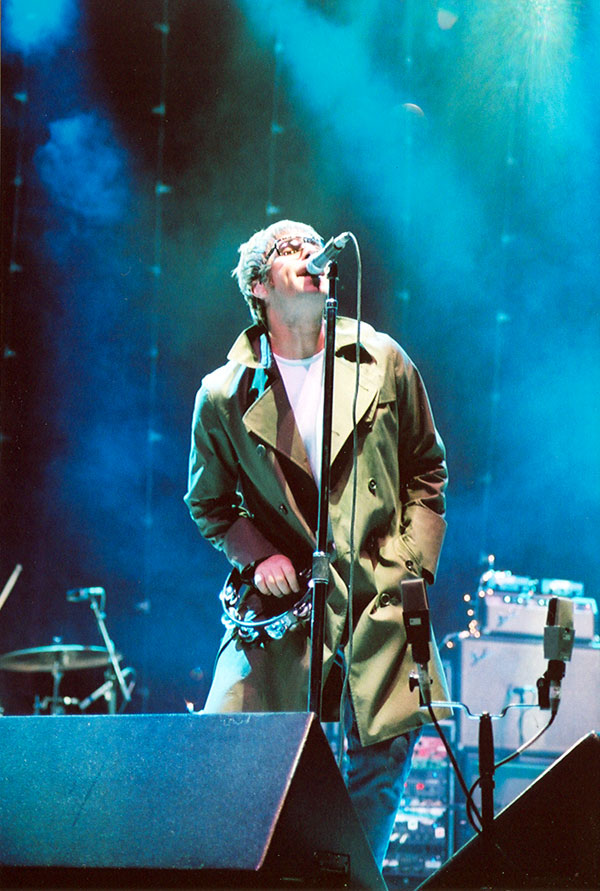

You’d need to have been without WiFi these past few months not to notice that Oasis are back in the public consciousness on a wave of 90s nostalgia.

This reunion tour, a performative truce undertaken for money (there is no new music in the offing), hasn’t exactly been a smooth experience. First up, the ticketing system was shown to be faulty, with touts causing a situation whereby at least four per cent of tickets have been selling at 40 times their resale value.

This caused the Starmer administration, not always noted for its responsiveness, to look into the matter. Culture Secretary Lisa Nandy released a statement: “The chance to see your favourite musicians or sports team live is something all of us enjoy and everyone deserves a fair shot at getting tickets – but for too long fans have had to endure the misery of touts hoovering up tickets for resale at vastly inflated prices.”

This is obviously true. There is an added awkwardness due to the fact that it’s the Gallagher brothers, meant to be on the side of the working people, who have presided over such high prices.

Secondly, a set list was leaked online, and Liam commented over X, jokily, that the set would be under an hour. Though this would turn out not to be true, enthusiasm was further dampened.

Time Capsule

Despite this bad start, it must be said that there is always something to be learned from nostalgia even if the reunion itself turns out to be a damp squib.

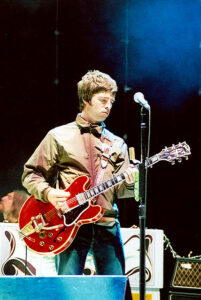

Oasis was all about nostalgia in the first place. In particular, it was a nostalgia for the Beatles and really what one might call a Lennon-first Beatles, where John, with his acerbic attitude, was slightly more to be celebrated that Paul with his essentially angelic gifts. Liam named his son Lennon not McCartney.

The success of Oasis was difficult to divorce from our openness to the particular kind of nostalgia they were peddling. The fact that the band was able to reignite a genuine excitement about a band who had only split up 24 years before the release of their album Definitely Maybe is instructive in itself.

What was the reason for it? For one thing, the world had moved so fast between the 1970s and 1994 that there seemed a definite gap. This sense was helped along by the fact of John Lennon’s tragic death in 1980, and by the rapid developments of Thatcherism. There was sufficient difference between the times. One doubts that people in, say, 1394 were quite so emotional about 1370 as we managed to be 600 years later about a similar passage of time.

Nevertheless, Oasis, and their rivals Blur and Pulp, arrived with news which shouldn’t have been particularly earth-shattering: the 1960s had been quite good. But there was another aspect in play: rock and roll is for the young, and their audience was young too. Born in 1980, I personally wouldn’t have heard the Beatles so early in life without the Gallagher brothers’ recommendation. Any appraisal of Oasis written by someone born in the 1980s should enclose an aside of gratitude.

Before the Web

Oasis’ brief period of ascendancy through their debut and their follow-up (What’s the Story) Morning Glory (1995) also inhabited that strange moment just before the world really became unrecognisable from what it had been: these bands were pre-Internet, and so also took advantage of the pre-Spotify industry model where things like Top of the Pops, the singles chart, and record labels mattered. Being signed meant everything. Nowadays everybody can get to market – or at least to some extent.

They couldn’t then, and so those who did had an exponential importance, and so were able to dominate the scene. If you weren’t signed you weren’t heard of – or heard.

So how good were Oasis? As one listens back to their two most famous albums, one can never be sure to what extent one’s enjoyment of the music is nostalgia-related and to what extent it has to do with the music itself. My guess is that the very fact we’re not sure is a sign that the music might not have endured well.

There are moments when to listen to Oasis is to be confronted by banality dressed up as inspiration. One also encounters subversiveness masquerading as deadly conformity.

It was Vladimir Nabokov who noted that in the 60s it was the shirtless drug-taking attendees at Woodstock – those who looked like, and claimed to be – the counterculture who were all along really the herd animals. The 1990s seem to have worked somewhat in the same way.

One thinks of the Adidas jumpers with two lines down the arms; the vapid swagger of the frontmen; the sad drug-taking ending up of most of them. It was a hedonism without any of the Timothy Leary and Aldous Huxley esoteric content. Some felt at the time that the advent of the Spice Girls and then Pop Idol spoiled the Britpop movement. But it was probably always redundant in the only place that mattered: within itself.

A La Vaudeville

This is partly because it was a rebellious movement which had nothing all that concrete to rebel against. Virtually all the gains had already been won, and so in some cases there was nothing to do but reiterate them, or even to simply utter nonsense.

The Sixties had railed against the Edwardian power structures. Peter Cook mocked the then prime minister Harold MacMillan to his face, and impersonated ignorant judges. But when you mock them a second time you are merely building on territory you have just won, and it was the winning of it that was the memorable thing.

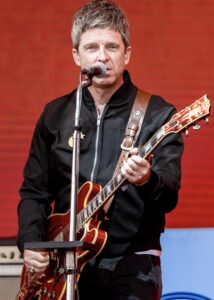

In ‘Cigarettes and Alcohol’, Noel Gallagher told a nation where cigarettes and alcohol were de rigeur that he wanted those things. This is a world away from Lennon’s explorations of the psyche in ‘Strawberry Fields Forever’, Harrison’s decision to go to India, or McCartney’s inspiration to use an entire orchestra in the middle section of ‘A Day in the Life’.

There is in fact a law in art that nothing much can be achieved in a given genre just after a great genius has come along. This is why there are no good plays in the years after Shakespeare’s death. Similarly, John Keats tried to write an epic poem in the early 1800s but found that Milton’s Paradise Lost, published in 1667, for the attempt to be viable. Great artists take up oxygen and the others come up behind them, panting for breath.

But there is nothing wrong per se with reiteration. But once you’ve established that Oasis not only attempted nothing new, but in fact committed themselves to pastiche, the question then becomes: how well did they carry off what was essentially a tribute act?

Words, Words, Words

To take the lyrics to start with, there is hardly an Oasis song that doesn’t mar itself with some version of nonsense. In writing things like: “I knew a girl called Elsa/she’s into Alka Seltzer’ in the song ‘Supersonic’ Gallagher was seeking to copy Lennon’s sublime gift for nonsense in ‘I am the Walrus’. The difference is that Lennon’s lineage goes back through Lewis Carroll, and at the same time is also capable of satirising the culture: “I am you as you are me as you are he and we are all together.”

His images are original – (‘see how they run like pigs from a gun’) – and emanate a strange confidence, even a certain knowledge. That song, and songs like ‘Glass Onion’ too, are what one might call serious jokes which work on two levels. This in turns means they can bear repeated listens. Meanwhile, Gallagher’s is just derivative of Lennon’s adding nothing but his own fandom.

She’s electric

She’s in a family full of eccentrics

She’s done things I’ve never expected

And I need more time

But if this doesn’t feel enough now, why did it feel so at the time? In one sense this is simple: we were younger then, and the world was too. Sometimes the excitement of a moment can catch us unawares, and we grow up around that moment, shedding that excitement as we go: the scales fall from our eyes. The art and music which endures is in some way impervious to the moment in which it arose.

Talkin’ ‘Bout My Generation

The reasons were also in part political, and sometimes seem to look forward to the levelling up debate which happened during the Johnson administration. This was the sound of Manchester, but made mainstream: the edgier sound of the Stone Roses given a popular twist.

But there are also points to be made in Oasis’ favour. To give Noel Gallagher his due, Oasis would never have been a pop culture moment at all, if it hadn’t been for Noel’s ability with a melody.

This was especially evident on the B sides: one thinks of ‘Half the World Away’, ‘Talk Tonight’, ‘and The Masterplan’ – songs written and sung by Noel, which always feel like they matter a bit more somehow. These are things he kept aside, and perhaps couldn’t quite bear to give away to a younger problem who he was already falling out with.

Even so, these songs still needed more work. Why, for instance, might somebody’s dreams be made of strawberry lemonade? There is an old and lovely Jewish saying that ‘Life is strawberries’ which would be a nice hook for a song, but with Gallagher one always feels that the words ‘made’ and ‘lemonade’ happened to rhyme. The rhyme was executed and left there: it considered just about good enough. But no true artist really feels that their first thought is sufficient. It was the Father Ted creator Graham Linehan who once pointed out that the best bit of writing is the second draft. With Oasis, everything feels like a first draft.

Likewise ‘Don’t Look Back in Anger’ would be better if we knew what Sally were waiting for; ‘Live Forever’ would be better if we knew more about where the garden is and what kind of thing might be growing there; and it is not clear if Champagne Supernova really means anything at all, meaning that we have seven minutes of euphoria without any decent reason to feel euphoric.

Despite all these reservations and more, as you listen to any highlights compilation of the 90s, you can feel that Oasis, more even than Blur or Pulp, can transport you to that time. Whatever the band’s deficiencies, they were invited to Number 10 by Tony Blair – and perhaps that shot of the then PM shaking hands with Noel was the defining image of that decade.

Thank You for the Music

We should add that if we want to understand that time, the music is more revealing than other art forms. True, the Millennium Dome and the London Eye, in their brash confidence seem to hint in architecture at Blair’s eventual hubris over Iraq, but they still feel like they had no true energy in them and that that was really their problem.

Likewise, although many, including Blur frontman Damon Albarn, enjoy the humorous nihilism of Martin Amis’ books like London Fields (1995), this was a time when people began to read less as the number of screens proliferated exponentially. It wasn’t really all that literary a time.

Finally, we all remember the Brit Art phenomenon and how we were meant to be impressed by Emin’s bedroom and Hirst’s shark. Who thinks about these things now? The truth is these were intellectual discussion points and never popular the way Britpop was. Nobody really cared about them then because they were never intended to stir the emotions and in the end that’s what counts.

But people cared about films like Trainspotting (which featured music written by Albarn) and they minded deeply about the music.

The Pleasure Principle

The music mattered because it was a gateway to hedonism. Hedonism is always a form of rebellion because it basically involves children giving their parents a fright about how far they might take it. In that sense Britpop was just an age-old generational acting up.

What is most notable is that nobody at the time seemed to pause and wonder if the example set by the Gallagher brothers was worth following or not. Blair, who had once been in a band The Ugly Rumours at university, calculated that it was a vote-winner to endorse them.

So, from the government down, it was time to binge-drink, be promiscuous and take drugs. ‘Lose control/hit a wall/but feel alright’ as Supergrass, one of the lesser bands of the time put it.

I can only find one warning about going too far in the whole cannon of Britpop. This is when Skunk Anansie in a song coincidentally called ‘Hedonism’ sing in the chorus: “Just because it feels good/doesn’t make it right.” They sound like John the Baptist surrounded by a sea of smoked spliffs.

In all this, there was only really Damon Albarn to satirise it and it’s not surprising that he clashed especially with Liam Gallagher. Albarn, a reader of Martin Amis as I have just noted, particularly promoted the Kinks. He looked like he understood that the excess around him wasn’t likely to prove in the long run all that it was cracked up to be. He satirised the package holidays scene in ‘Girls and Boys’, the mores of a typical London neighbourhood in ‘Parklife’, the longing for a placebo in ‘The Universal’, and the rat race in ‘Country Life’.

In one sense the Blur v Oasis battle of the bands was a simple class contest. The battle was initially won in the short term by Blur when ‘Country Life’ went to number one ahead of Oasis’ dire ‘Roll With It’.

In the medium term, Albarn was more sensitive to the opinions of other people than his rivals and so less suited to fame than they were. In the end, the band’s self-loathing album The Great Escape couldn’t compete with the carefreeness of (What’s the Story) Morning Glory.

Sharp tongues

But it’s possible today to wonder about the vitriol which the whole thing sparked. In the first place it had to do with the personalities themselves. Noel said he wanted Damon to get AIDS, and Damon wasn’t the sort of person to back down either. This childishness was gleefully reported during a time when, unlike today, the economy was thriving, and Blair was heading towards a gigantic majority.

There was simply less political jeopardy in the air than we’re currently used to: during the era of Brexit and Covid, we only have time for feelgood music stories around Coldplay and Taylor Swift. There is little debate in the culture headlines; that’s all disappeared back into the front pages where it probably belongs.

But really the issue was that the one was satirising the other in song – that is, Blur was capable of mocking Oasis, but the same wasn’t necessarily true in reverse. In interview, Noel can be as amusing as anyone, but it’s hard to imagine him writing ‘Charmless Man’. Albarn could easily spend all day satirising British society at a piano.

But in the end Albarn succumbed to the very mores he was meant to be mocking. As we move to the present time, the Blur singer cuts a grim figure on the documentary To The End. It’s a reminder that the best satirists are able to have lives wholly apart from the flaws which they point to in their work. Ian Hislop is a little like this; so too is Rory Bremner. Albarn, though he knew the 90s were vacuous and problematic, got sucked in.

There’s no shame in that – most of us did for a time, and then we grew up. This is the peculiar nature of reunion tours – they represent a kind of collective refusal to grow up, and for those of us who watch a brief bit of time travelling. In Oasis’ case there is little to celebrate besides entering this time loop, and realising we’re looking at it all with slightly wiser eyes now.