BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

You may not have heard of the late Jim Haynes, but he was a pioneer in the world of hospitality. His insight was simple: we should get to meet as many people as possible. Haynes died in January 2021 and was known in his obituaries as ‘the man who invited the world over to dinner’.

He did just that. Haynes lived in Paris in the 14th arrondisement, and on Sunday evenings would have an open-door policy. Anyone could come. His death during the pandemic, saddening though it was, arguably made a kind of sense – as if a man who all along craved human interaction, should exit the world when that interaction was no longer possible.

And what of those of us left behind who might want to honour his spirit? As the Deliveroos mount, and as – to quote the restauranteur Jeremy King – we remain ‘entombed in our homes’ that seems harder and harder.

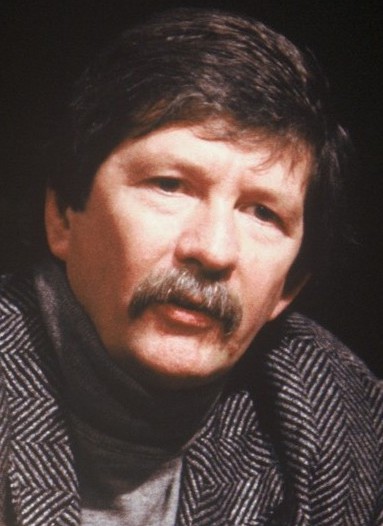

Jim Haynes (1933-21): ‘The Man who Invited the World for Dinner’. (Credit: Commons licence 3.0, attributed to Open Media Ltd.)

But I would like to present the solution in the shape of a remarkable Israeli chef, Orr Barry, who has become a phenomenon in south-east London during the pandemic.

Like all the best things from The Queen’s Gambit to the furlough scheme, Barry has operated by word of mouth. In Dulwich, if you bump into someone friendly at school pick-up or in the park, the conversation might turn to Safta Cook, the name of Barry’s highly personal delivery venture. “Did you try Orr on Friday night?” It was a safe topic of conversation. You could be reasonably sure the person you were speaking with had.

I meet Barry outside his spot on Lordship Lane, and ask him why food matters so much to him. “For me, it’s something that takes you into memories and nice moments, certain feelings like you’re trying to kind of recreate something very social.” That’s what makes Barry’s food special – the sense that he is trying to communicate to his customers something almost intangible.

Another way to put it is to say he’s cooking with love. That has to do partly with his past. Barry grew up in the centre of Israel about equidistant between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem, but his heritage mixes central European, northern African and the Middle East. That comes across in his food.

But Safta Cook was also created out of necessity. Having been furloughed from his job as a new product development chef at Gail’s, Barry realised he had to keep cooking. Moreover, he could still access interesting ingredients: “I realised there was no limitation of supply. I wanted to be open and to tell people who I am through food – it was a way of practising my heritage.”

What distinguishes a Barry meal is the eclectic playfulness of his cooking, as well as the care – the handmade menu, the personal delivery – with which it’s presented. This is also healthy food at a time when the temptation – yielded to all too often by some of us – has been to fall back on pizzas and burgers. “You don’t want to go through an entire pandemic on pizzas,” Barry commiserates.

Orr Barry at his Saturday stall on Lordship Lane

But really Barry has demonstrated the possibilities of food when it comes to community. “Now when we’re walking down my street, I know all the neighbours,” he says, proudly. His is a very pandemic story – it is an example of how we might still reach one another while separated from one another.

There’s another aspect to this. Stuck in our locality, Barry invites the world into your home, just as in his different way Jim Haynes used to do. “I love to take the menu sometimes into the Jewish tradition – but sometimes you’ll find a twist of Asian food, whatever interests me at the time. I try not to repeat myself, because people want the unknown.”

We’ve learned that freedom and hope are deeply intertwined: in ordinary times, we feel optimistic about the time ahead, because it’s in our gift to make of it what we will. That’s what the pandemic has robbed us of: instead of the ramifications of freedom, we see only limits. Barry is in opposition to that.

Barry – who used to run the no.1 Trip Advisor-rated restaurant in Tel Aviv – doesn’t want to turn Safta Cook into a restaurant once the restrictions are lifted: “A restaurant is like a military regime,” he says.

The following Saturday, I show up at Barry’s Saturday morning stand, and purchase some oysters, a shucker knife, and a mix of salads and vegetables, then back home eat my best meal of the pandemic. As I imagine the food must have tasted at Haynes’ house in Paris, Barry’s tastes of that rare thing nowadays: liberty.

Christopher Jackson