BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

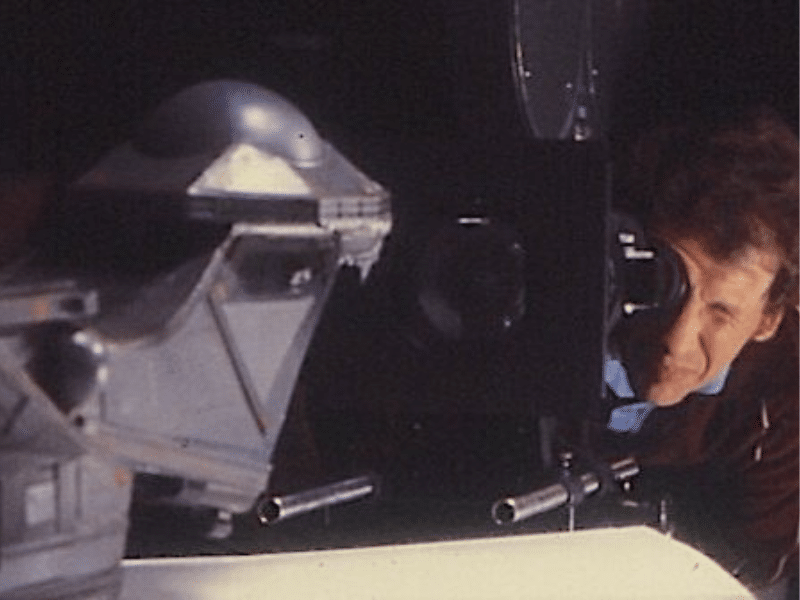

Photographer, artist and erstwhile Dr Who director, Paul Joyce, offers an insight into the making of the Time Lord…

One can almost hear the sigh of relief breathed by Idris Elba when at last the young cub was painfully torn from David Tennant’s side in an awkward and over-extended CGI sequence. A nod maybe to the book of Genesis but no mention of additional ribs or, thanks be, even a glance towards the other candidate for Eve’s existence, the baculum. Rather we are presented with an athletic looking young black actor of undoubted Achillean appeal and bizarrely sporting only bone-white underpants for the remainder of the show. For my money quite a lot of fuss over barely spilt milk. Welcome to the world of “Bi-Regeneration” (as opposed to simply ‘bi’) which will allow Tennant whose Hamlet and no doubt Macbeth and Lear will all be overshadowed at least in legacy terms, by his stuttering appearances as The Time Lord. As one horrified fan just wrote: “what the f*** so what now we get 2 doctors flying about ????” It is clear our David will not leave the show lying down.

In a hagiographic follow-up documentary aired immediately after the show’s first airing, an uncomfortable looking presenter, wielding an exaggerated Welsh accent (to remind us of the show’s Celtic credentials,) wandered around the set to demonstrate just how good the CGI is in the transmitted version. His first choice of interviewees included the 2nd assistant director, a Runner and a puppeteer. Oh yes, plus one of the producers who appeared briefly as did the show’s grandmaster, Russell T. Davies. Any documentary worth its salt covering filming of really any kind would usually figure the director at some point as being at least nominally a captain on the ship. But not here, not now, which symbolises for me the vacuum at the heart of Dr Who in its ongoing form since my brief tenure there 40 years ago. The director nowadays can be anyone more or less: in my time that might be a promoted first assistant director or junior producer eager to lap up the BBC philosophy of absolute loyalty to the crown (or in other words TV Centre). For me that view has not shifted much in the last four decades at least.

My quite genuine admiration for the show’s initial 20 minutes or so rested, now I consider my reaction more carefully, on mainly technical excellence; these included stunning views of cities with beautiful futuristic buildings running alongside believable recreations of Soho streets 100 years ago. British TV is attempting and succeeding in matching the mighty Hollywood dollar, aided by our indigenous and unequalled Special Effects facilities. The bolted-on documentary also showed what seemed like an army of Steadicam operators flying hither and thither about the set apparently filming anything that moved. I came from an era where budgets were tiny, special effects barely obtainable, and working conditions today would be truncated overnight by a number of trade unions and government acts.

Paul Joyce second from left with Tom Baker

In my day I had to beg, borrow and finally steal the first truly portable camera to enter the BBC’s hallowed walls, called, as I barely can remember, an Ikigami. Added to which I faced a hostile management at the BBC eager to have me fired, and with key elements of my crew resentful of my very presence on set. In retrospect my reputation was probably firmly set on its course towards oblivion long before I took up the reins on “Warriors Gate”.

It is important to mention that there is one crucial difference concerning a director’s authority between my time, and pre-production conditions today, and that is that he or she has no official control over casting, a major contribution to the success of any series. I like to think that my four episodes of “Warriors Gate” where I was totally responsible for casting (Clifford Rose; Kenneth Cope; David Weston, etc.), survives as well as many in those middle years, because of the strength and diversity of the talent I chose to work with. This was aided by basically a stroke of fate which left myself and the script editor, Chris Bidmead, with unworkable scripts which we had to re-write over the course of a week, thus losing valuable rehearsal time which I was not able to recover. Having altered the characterisations in our additions, this meant I had an intimate knowledge of what made my characters tick. So it was important to let my two Laurel and Hardy actors ( Freddie Earle and Harry Waters ) know that their roots had been laid down in the work of many authors such as Samuel Beckett and Tom Stoppard. A middle ranking BBC executive thrust into the role of casting director would have no notion of these, hopefully subtle, nods to familiar characters which can be traced right back to the Bard himself (aka.Rosencrantz and Gildernstern). So one crucial element of constructing a coherent show is cut away at a stroke, like nadgers from a bullock. This change from my days was not a spur of the moment management decision, but one made incrementally over time; one leading to a gradual erosion of the director’s authority, further buttressing those twin pillars of the BBC Establishment, the producer and the writer.

A friend of mine, a well-known presenter and actor, also well informed on the history of Dr Who, said that one director had told him that British TV deliberately places an executive layer in place in order “to protect the audience from the director”. I found this a very intriguing notion and it is certainly true that the BBC keeps directors as blank as the outline posted on eBay or Instagram before you fill in your personal details. Ghostly interchangeable presences flitting from drama to drama, obedient boys and girls wedded to the great corporation and fully plugged-in to its necessary support systems. It was certainly my experience both on “Warriors Gate” and a Play for Today that I wrote and directed in Pebble Mill, that one is expected to work to a rigorous schedule which takes no account of creative differences, matters of interpretation, second thoughts or even the weather. And going over a studio session by a single minute means the plug is literally pulled. Now this practice might have changed by now, and I really hope it has, but the driving force behind BBC programming is to produce saleable product first and foremost. In the past the BBC nurtured towering talents, the likes of Ken Russell, Peter Watkins, Ken Loach and Tony Garnett, but those days are long gone, lost like traces of special-effects gunpowder on the fields of Culloden. All of the above mentioned fled from TV into the alternative minefield of film-making where the stakes are even higher but success comes to those with persistence and talent, finally rewarded by the enviable credit, “A Film by…”

A scouting shot by Paul Joyce for Dr Who at Powys Castle

The recent strike by film and TV writers in the US has reached an uneasy compromise but the threat of AI hangs over all of us. Mozart is already composing his 42nd symphony. But if actors are frightened of being cloned and resurrected from the dead, what about directors? Could we make one like Sam Peckinpah whenever we want a great shoot-out? Or a Spielberg for any Si-fi or underwater picture? Seriously now, I can see a time when a robot could not only organise a script, but create a workable storyboard, issue instructions to actors based on pre-ordained movements (computer checked beforehand) then supervise an individual shot; a robotic decision could then be based on a) if everything in frame was in focus, b) actors delivered their lines without hesitation or repetition c) any special effect proceeded according to plan. Voila! Direction by numbers, but aren’t we almost there already? The days of “Sorry sir, there is a hair in the gate” are well behind us now.

There have undoubtably been fine directors on the series during its unprecedented 60 year run, but for me the problem remains, now as it actually did just as well then, how few have gone on to become true originators and in creative terms, real auteurs. In America’s golden age of live TV, mighty talents like Sidney Lumet and John Frankenheimer, Michael Mann and Robert Altman emerged and then went on to become kings in the kingdom of Hollywood films. It is difficult to come up with a complementary list here in the UK.

I can see why more or less anyone competently trained in state-of-the-art technical capacities, particularly computer graphics and CGI generated images, could command a set of this kind today, and bow to the will of the writer’s vision. In this sense nothing has changed since “Warriors Gate” where I tried to bring at least a hint of the director as auteur to the proceedings. But I was cut off at the knees by the establishment’s twin-peaks, namely the producer and the writer. This has barely changed from the era of the show’s founding producer, Verity Lambert up to and including Russell T. Davies today. So a homogeneous product is born to satisfy the needs of voracious salesmen promoting BBC Worldwide, and where a show is judged by its longevity rather than on its individual and intrinsic merits. Who amongst us older directors can forget that the first episode of the Peter Falk TV series Columbo was directed by a teenage Steven Spielberg?

So here we have it, an all-new, no-expense spared Russell T. Davies extravaganza with bells and whistles (literally), flying galleon ships (straight out of Pirates of the Caribbean) and a baby hungry monster Goblin (or was it Gremlin) looking like a giant overfed cowpat. What more could a child want, I asked myself, settling down on the sofa to watch with my soon-to-be teenaged granddaughter, Zsofia? She took the precaution of supplying us with large fluffy cushions to hide behind during the scary bits. Scary bits? Well, that’s another story…

Of course, we are all watching out for the hugely talented Ncuti Gatwa to don a pair of real trousers after flouncing around in boxer shorts for his prequel introduction. And he gave us that smile as well, countless times, showing a set of teeth well capable of blinding half the audience as well as severing the appendages of any alien previous seen on the series. Looks, charisma, athleticism and even I suspect a good singing voice. What more can one ask for, except perhaps a new companion to bounce off? “Say no more”, mouths Russell T. and with a sweep of his pen, lo and behold, a companion appears as blond as he is black and as straight as he is gay. The whole world in his arms!

So where is the problem? At the very root, I’m afraid, with the very bedrock of the programme, the script itself. Part religious analogy (baby in a manger) part time-travel with missing baby (black or white, both are there, but which is which) and a chorus of singing Gremlins (or maybe they are meant to be Goblins?). It all seemed to hinge on some kind of time warp (but unfortunately not as funny as Rocky Horror) where Ncuti rescues one of the babies who apparently develops rapidly into his next companion, a blond goddess called Ruby (Millie Gibson). All well and good but what about the story line in an episode which must have cost, in my calculation at least, the BBC about 6289 licence fees? Just one word covers that I fear, simply “cobblers”.

After the first 40 minutes or so, when a nest of Goblins/Gremlins formed a chorus line and prepared to belt out something sounding like “Hello Dolly”. I turned to dumb-struck Zsofia and asked if she could make head nor tail of what was going on? She shook her head sadly, cushion still rooted firmly in her lap. “What’s that for then” I asked her. “Oh” she replied, “I was watching an old Matt Smith episode of some dolls in a cupboard. Really scary!” “What about this one, do you think”, I enquired gently. After a momentary pause came back the unequivocal: “Not scary enough!”