BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson tours a fine new exhibition at the Sainsbury Centre about the many ways drugs impact our lives

After reading about the death of Liam Payne in Buenos Aries recently, one felt a sense of grim recognition. It was another story of a famous person with a bleak ending up, where the prime mover in the tragedy was drug addiction. This followed on from Matthew Perry‘s sad death the previous year.

But you don’t have to look far in recent history to find others: Amy Winehouse, Jimi Hendrix, Jim Morrison, Michael Hutchence. It is a grim roll call of squandered talent. The trouble with talent is that it all too often distracts you from learning how to live. Know thyself, was the injunction above the entrance to Plato’s Academy.

Drugs certainly can prevent that process, but the Sainsbury Centre has embarked on a larger mission: to consider drugs from many angles and therefore to arrive at a deeper sense of what drugs have meant to the species recreationally, socially, politically, in healthcare, as well as artistically and even spiritually. The results are shown in a series of exhibitions, and also in an accompanying book which is both well-written and beautifully designed.

It was Gore Vidal who, in his usual lordly manner, said he’d tried each drug and rejected them all. He settled in the end on alcohol as his main source of recreation and it didn’t do him a huge amount of good, especially in his old age. But most people in their forties and fifties today will have dabbled in some form of drug, usually when too young to know precisely what kind of self they were supposedly meant to be experimenting with.

This has without question hugely contributed to the mental health crisis which we see all around us. It manifests all too often as an employability problem, but this is ordinarily a symptom of addiction and not a cause.

There is much in this exhibition to warn us off drugs, with heroin singled out as a particular disaster area. This was the tipple of the great Nick Cave, and he got through by the skin of his teeth to his present incarnation as a musical seer and global agony uncle.

Cave always made sure he was at his desk at 9am, and wrote some of the great songs of this or any age while in the clutches of this particularly brutal drug. The section of the exhibition called Heroin Falls makes it clear that the high-functioning heroin addict is likely to be an extremely rare phenomenon.

One such is Graham MacIndoe who chronicles his own addiction in photos of raw power. MacIndoe wasn’t robbed of agency by his addiction – or not entirely – and found that the drug made him focus with considerable obsessiveness on lighting his pictures.

My Addiction, Graham MacIndoe

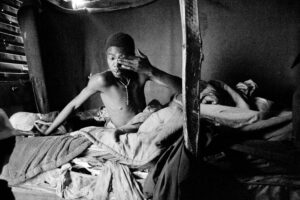

And yet heroin remains a grim topic whatever spin you put on it. That’s even more the case when you consider the current trend in South Africa for Nyaope, known as ‘poor man’s heroin’. This is highly addictive and can contain anything from detergent to rat poison or antiretroviral medications. Anybody who has been to Johannesburg knows that it can be hell on earth: and here’s why.

SOUTH AFRICA. Johannesburg. Thokoza. 2015. Thabang waking up in the early hours of the morning.

SOUTH AFRICA. Johannesburg. Katlehong. 2015. Bathing in Katlehong after a long day.

But the Sainsbury Centre frequently points out that drug use hasn’t always been this destructive. The message is that, as with anything in life, it helps to know what you’re doing. There still exist today peoples in South America with a positive relationship to Ayahuasca.

Richard Evans Schultes, The Cofan Family that met Schultes at Canejo, Rio Sucumbios, April 1942

Richard Evans Schultes, Cano Guacaya, Miritiparana, 1962

Richard Evans Scultes, Youth on the Paramo of San Antonio above the Valley of Subondoy, 1941

These pictures show another setting to drug exploration: we are in the great outdoors where drugs really originate. Quite simply, they grow in nature, and it is a relief to the viewer to be out of the urban setting where drug addiction so often goes badly wrong, into landscapes where the existence of drugs has a saner context.

As interesting as they are, they rather pale in comparison to some of the images of visionary art in this exhibition, the best of which is Robert Venosa’s Ayahuasca Dream, 1994.

Robert Venosa, Ayahuasca Dream, 1994

All one can say about this picture is that if this is how the world looks on ayahuasca, you’d be a bit crazy not to want to try some. This is why people take drugs: they sense that the external world might be an end effect of something larger and that drugs might be a way to move towards that cause.

Venosa’s picture, with its sense of a drama we can’t quite grasp conducted involving figures whose identity we only vaguely know will touch a chord with many. It is impossible to look at something of this scale and beauty, and feel that drugs can be of no benefit to humankind.

Most people suspect that their mind is operating at a very low percentage as they conduct the rote tasks which the modern world can sometimes seem to require of them. They know they’re capable of more.

I think it’s more than possible to do all that in a state of sobriety, and that route will be better in the vast majority of cases, simply because so many people lack the willpower not to fall into perennial addiction. Who can sort the real drug mentors in the Amazon jungle from the charlatans?

But the Sainsbury Centre has done a great thing by tackling this subject in such an encyclopaedic fashion to remind us that though we each have our inner Amy Winehouse where everything can go badly wrong, we also potentially have a sort of Sergeant Pepper Lonely Hearts Club Band within as well – a new level to go to, whoever we are.

For more information go to: https://www.sainsburycentre.ac.uk/