BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

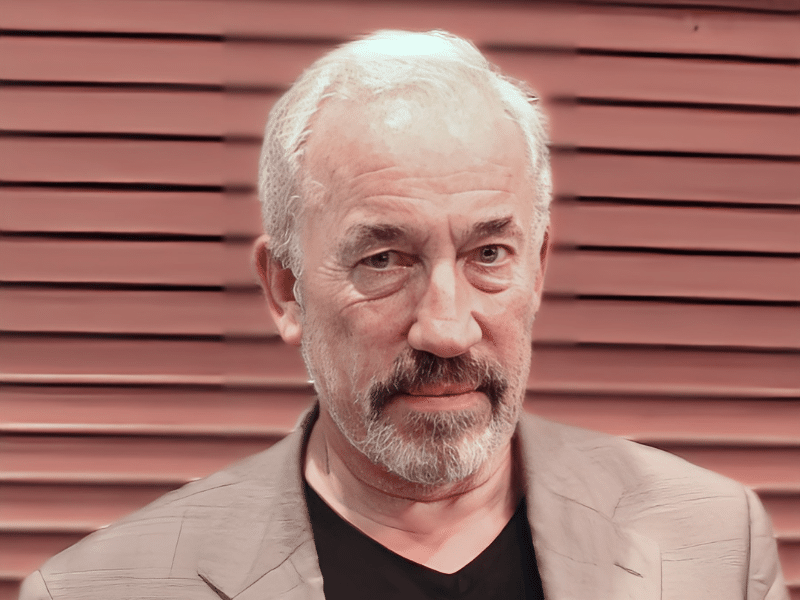

Simon Callow

I am sometimes asked by young people who want to be actors whether I can help – realistically, there’s not much I can do because I’m not Laurence Olivier so I can’t invite people to come and work in my theatre.

But when asked for advice, I tell young people that it’s a very, very hard life. If you are considering this route, you must first ask yourself: “Do you need to be an actor?” Unless your life depends on it – unless it’s the only thing that you can imagine yourself doing – then don’t even think about it because it’s a life of rejection and disappointment.

I lived in Streatham until I was five and then I went to live in Berkshire where my mother was the school secretary for two years, before we returned to Streatham. When I was nine, I went to Africa; we returned eventually in 1962, and I lived then in Gypsy Hill.

I didn’t think I was going to be an artist until much later. I had no idea but my grandmother had been a singer, and even been on the stage. She was a contralto – one of those deep female voices that you don’t really hear so much nowadays. But the life was not for her since she suffered quite badly from nerves so big concerts were difficult. However, she did sing at the Albert Hall to celebrate the end of the war in 1919.

She was a very theatrical human being as was her father – who was Danish and had been a clown in the Tivoli Club, and then became a ringmaster in Copenhagen where he married my great grandmother, a bare back horse rider. He came from a long line of equestrian folk and came to London and became an impresario. So theatre was there but not close to hand.

As a child I was rather extrovert. When I was out with my grandmother shopping I would be doing routines and someone said to my grandmother: “This child should be on stage, he is very gifted.” My grandmother was delighted by that idea and told my mother the good news and my mother said: “Over my dead body!”

When I was in Africa, aged 9 or 12, in Lusaka, Zambia at school we did little playlets but tiny stuff. When I went to boarding school in South Africa at a school called St Aidens in what was then Grahamstown, I did actually act in plays but I have very little memory of it – except there is a photograph of me dressed up as an angry old man shaking my fist.

When I came back to England, I went to a school called the London Oratory which was in those days in Chelsea but subsequently moved to Fulham and became quite a famous school partly because Tony Blair went there. It was a pretty terrible school and we had no drama at all. I knew nothing about acting at all. But London was all around me, and from my personal experience, I was overwhelmed by the work of the National Theatre and the Old Vic. I wrote a letter to Laurence Olivier who suggested that I might apply for a job in the box office.

Since that time, I’ve been very lucky in my career, and I do get recognised, especially after Four Weddings and A Funeral. However I’m not Jennifer Lopez and I’m not Brad Pitt so the true burdens of fame aren’t something I’ve had to bear.

I’ve had my share of setbacks. Not all movie executives or financiers are especially responsive to my art, but then that’s especially normal when people cross over from theatre into film. Take Tom Stoppard, as an example, who has sometimes seen his scripts go unmade: he is essentially a playwright, and he knows what he’s doing. But when executives read a Tom Stoppard script they probably don’t see dollar signs. Instead they think: “This is very clever, this is very interesting but where’s the money and the audience?”

I have sometimes had to face the fact that I’m not commercial. I directed one film called The Ballad of the Sad Café which was a sort of mildly respected flop. An art house flop is the worst sort of film you can make. You could make an art house success, and that’s very good. You can also make a commercial flop – but if you brought it in on time and under budget then you would still be a safe pair of hands. But an art house flop is an absolute no-no.

Even so, things are looking up and I have some movies in the pipeline, which are very promising. But the thing about making movies is that it’s very expensive, and people don’t like spending their money – except when they sometimes go mad and think that they are making art like Warren Beatty’s famous flop Ishtar, where everybody spent more and more money because he was Warren Beatty.

This is all partly why I am quite nervous when I am doing plays with other people: on my own I am my own master completely and even if were to forget a lump of the text I can make it up, and I am now quite good at improvising Dickens and Shakespeare. I note that the solo play is becoming a trend. I see that Eddie Izzard has just done Great Expectations, and that Andrew Scott has done Uncle Vanya as a one man show. The only novel that I have ever done as a one man show is A Christmas Carol which works because it is this amazing magical performance where you can jump from one scene to another: the narrator of A Christmas Carol in our version is a conjurer and that makes sense.

I am often asked about my next one man show. I’m sure Gore Vidal would make an entertaining evening but I don’t think I would be the person to do it. I am always nobbling writers to write me things and they are always a bit daunted by it. They are adapting at the moment a novel by an American novelist called John Clinch. Clinch he writes two kinds of novels: straightforward narratives and prequels somehow interconnected to already existing novels. One he wrote was called Marley; I happened to review it for The New York Times – and I immediately took an option out on it because I could see huge cinematic potential in it, as well as solo performance potential. I’m on a third draft of it, and getting close to something performable now.

I’ve now been writing about Orson Welles for over a quarter of a century: I have become a more nuanced viewer of the human scene than I was when I was younger but that’s not surprising. But lately I’ve been thinking about fiction too: there are about half a dozen novels swirling around in my brain and I would love to write them, but I have so many other things that I have still got to do before that. I also want to write about my family – but not in fictional form: I have just got to get it out of my system.