BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson

Geniuses never do what we want them to: if they did, they’d be just like us. There’s recompense for the dismay we sometimes feel at the trajectory of our heroes. After the initial confusion comes comprehension, forgiveness, and awe – followed by amnesia about the traversal of that progression. Soon you forget why you ever struggled; they’ve normalised a place you’d never have got to under your own steam.

Such phases – capped with delight – apply to the work of those of high achievement whose output we get to follow in real time. Imagine a fan of the Picasso blue period confronted with the invention of Cubism eight years before the outbreak of the First World War; or the Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man devotee faced in 1922 with the mystifying beauties of Ulysses.

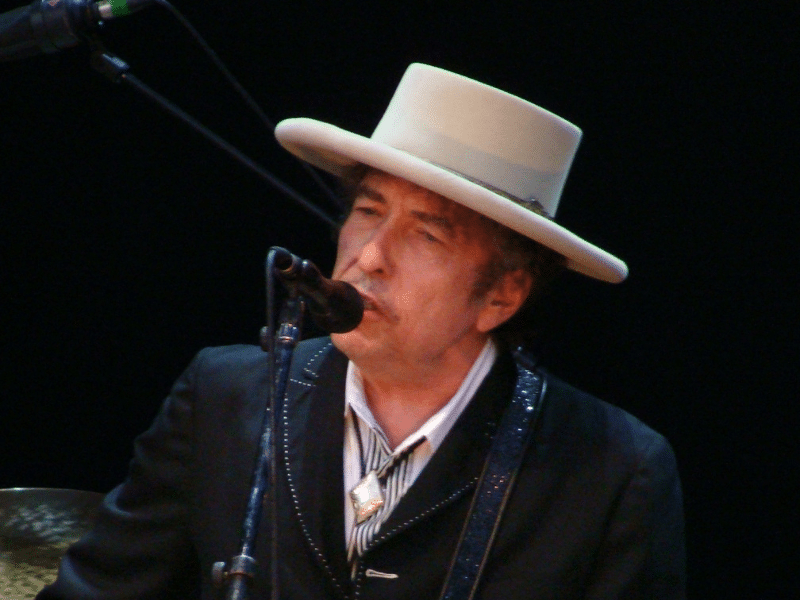

Bob Dylan is the chief perpetrator today of this kind of rewarding bafflement. He’s been outmanoeuvring us for 60 years.

When we were used to Elvis’ platitudes, he gave us poetic song. When we demanded more folk, he smiled and gave us skirling Rimbaud-esque electric guitar; when we asked for more of that, he more or less invented Christian rock. By the mid-1980s we wanted to hear his hits as on his records, so he played them out of time and out of tune for around 30 years.

It didn’t stop there. When we didn’t care whether he painted or sculpted at all, he did both – and well. By the 1960s, when we were advising him to write something comprehensible, he eventually handed down from on high the wild madness of Tarantula (1971). Later, when we didn’t solicit his recollections, he wrote Chronicles Vol. 1 (2004).

Having greatly enjoyed that, we pleaded for a second volume, but he didn’t give us one, despite the logic that a first volume implies and necessitates a second.

In 2016, we gave him a Nobel Prize for Literature, to nudge him along in that endeavour. That didn’t work either. He didn’t accept the prize with any degree of normality, and instead delivered a speech with a backing track which turned out to be the beginning not of anything literary, but instead a prototype for ‘Murder Most Foul’. This 17-minute song (which always seems to me to finish in about four, as if Dylan has bent time) was then released at the start of the pandemic, making sure we paid attention to a completely new kind of song just when we had nowhere to go and couldn’t avoid listening to it.

But back in the late 1990s, when silence had seemed to be the best that could be hoped for, he gave us a masterpiece Time Out of Mind. Even that was complicated: it was produced by Daniel Lanois in a murky swampy sound which meant Dylan had to release a re-recorded version earlier this year, which many fans – this reviewer included – now consider to the be the right one.

By 2023, the strangenesses keep forking across our vision like some sort of improbable laser system. Last year, Dylan gave us The Philosophy of Modern Song (2022), which turned out to have no philosophy in it, and even less modern song. He then matter-of-factly released a new whisky. What will he do next? Become the world’s first 82-year-old ballet-dancer?

But every time you learn to be content, and to want more of what you didn’t need to begin with. Everything’s a phase, a stop, a navigation point. His career is all movement, restlessness, energy – for the listener, it’s a process of constant addled reconciliation to puzzlement.

All of this accounts for the particular note of coverage which attaches itself to everything Dylan does: it is the sort of excitable speculation which would make sense only in anticipation of a thing. Instead, the debate is occurring at the tangible – an album, a book, a painting – which is there in plain sight.

Shadow Kingdom was initially an esoteric streamed film released last year for the cheeky ticket price of $25. It entailed Dylan and some actors performing in a fictional Casablanca-style bar called The Bon Bon Club. The music percolated around the Internet, but here is the official release.

Instead of naming it Bootlegs Vol. 18 as he might have done, Dylan has allowed these nostalgic recordings to stand to one side under this title.

This decision draws additional attention to the title itself. Readers of Richard Thomas’ study Why Dylan Matters – a moreish work which shows definitively how Dylan has lately been drawing on the classical world – may think of Homer’s and Virgil’s underworlds, and embark on the futile process of defining what the direct connotation might be.

It doesn’t matter. What’s clear is that at the peak of cultural achievement at the age of 82, Dylan is reaching into pockets of forgotten time and doing some crucial rearranging, and possibly purifying. Inversions, reflections and opposites: it’s Dylan through a distorting mirror – a negative.

So how does that sound? First up, he has chosen his set list cunningly. Though billed as a release of Dylan’s early hits, none of these – with the possible exceptions of ‘Forever Young’ and ‘It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue’ – is really first-tier Dylan in terms of being well-known. An album of his actual hits would have included ‘Blowin’ in the Wind’, ‘Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright’, ‘Mr. Tambourine Man’, ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ and ‘Lay, Lady Lay’.

Instead find ourselves in obscure suburbs of the songbook, and perhaps that’s part of the exercise: to remind us of those corners of the greatest oeuvre in post-War music which we might not have been listening to. So we get a balladeering ‘Tombstone Blues’, an almost entirely rewritten ‘To Be Alone With You’, and a deliciously slow ‘Pledging My Time’.

The other way in which the ‘Shadow Kingdom’ effect is achieved is through the absence of drums. The album in fact prompts an interesting thought experiment: what would the history of recent music have been like without drums, and therefore without the centrality of the animalistic and Dionysian figure of the drummer? Without drums we can still have rhythm – as these tracks do. But Dylan appears to be saying that other worlds – other kingdoms – are possible.

The opener is ‘When I Paint My Masterpiece’ which, like the album’s promotional single ‘Watching the River Flow’, was written in 1971. Both songs were first recorded by The Band later that same year, making them twins of a kind. These fine and underrated songs were written during that quiet period when Dylan was predominantly raising children. That ‘domestic happiness’ phase, when child-rearing swerved in to diminish his output, not only proved him mortal but proved him gratifyingly subject to the laws of parenting.

It’s of great interest that he feels the need to return to these two compositions, as if to reconsider the implications of a lost tranquillity. A lyrical change which dates from October 2019 nowadays occurs in the first stanza of ‘When I Paint My Masterpiece’. He’s no longer going back to his Rome hotel room for a date with Botticelli’s niece. Instead he’s:

gonna wash my clothes,

scrape off all the grease

gonna lock my doors

and turn my back on the world for a while

and stay right there ’til I paint my masterpiece.

Which is marvellous. The original line about ‘Botticelli’s niece’ – though a good rhyme, and amusing idea – probably didn’t quite fit, the painter having been a Florentine, and the song is meant to be set in Rome (I’m not sure I particularly like that towards the end it relocates to Brussels). But then Cicero’s niece might have been too remote and improbable a notion – better to think of another rhyme altogether.

There are hundreds of moments like this on Shadow Kingdom. Gore Vidal once wrote a memoir called Palimpsest (1995) a title which might also have suited this album. We are in permanent dialogue here between Dylan’s octogenarian self, and the younger succession of selves who wrote these songs.

This conversation across time takes three forms. Occasionally, we get a lyrical rewrite. Most notably ‘To Be Alone With You’ is almost entirely rewritten and is therefore the most important recording here, essentially amounting to the first new work by Dylan since 2020’s Rough and Rowdy Ways.

It has been noted that late Dylan contains an alarming number of instances of violent language, and there is probably more work to do to understand precisely what he’s doing here. This stanza in the otherwise lovely ‘Soon After Midnight’ from 2012’s The Tempest might be taken as representative:

They chirp and they chatter

What does it matter?

They lie and dine in their blood

Two-timing Slim

Who’s ever heard of him?

I’ll drag his corpse through the mud

We naturally suppose that this stanza isn’t autobiographical unless the next chapter in this storied career is to be The Trial of Bob Dylan. What seems to be happening is that he is admitting the possibility of murder into the consciousness of his characters: right next to all the grand and lyrical feelings of love and romance, we get the strange static of murderous resentment.

This does in fact happen in the human mind – and most particularly, in the jealous human mind – but it is still tremendously bold of Dylan to admit this into the world of popular song. It’s probably the chief development in late Dylan: it would be odd, for instance, if the singer were to start dreaming of murder in the middle of ‘Lay, Lady, Lay’.

All of which makes the rewrite of ‘To Be Alone With You’ – from the same album as ‘Lay, Lady, Lay’ – fascinating. On the 1967 Nashville Skyline recording the final words were relatively anodyne in keeping with that – intentionally? – tame album:

They say that nighttime is the right time

To be with the one you love

Too many thoughts get in the way in the day

But you’re always what I’m thinkin’ of

I wish the night was here

Bringin’ me all of your charms

When only you are near

To hold me in your arms

I’ll always thank the Lord

When my working day is through

I get my sweet reward

To be alone with you

When Dylan wrote that he was trying to put clear water between his latest work and the complex poetry of the great mid-1960s albums which culminated in Blonde on Blonde (1966). Now, in 2023, the whole thing is completely rewritten:

I’m collecting my thoughts in a pattern

Movin’ from place to place

Steppin’ out into the dark night

Steppin’ out into space

What happened to me, darlin’?

What was it you saw?

Did I kill somebody?

Did I escape the law?

Got my heart in my mouth

My eyes are still blue

My mortal bliss

Is to be alone with you

My mortal bliss

Is to be alone with you

The way Dylan sings ‘my mortal bliss’ – especially the second time, full of gravelly yearn – is his great vocal moment on this album. But why are we suddenly talking about killing? We can be sure that if the narrator had killed somebody, he would remember. Assuming therefore that he hasn’t, it seems likely that his love is ignoring him for no clear reason, and he’s asking rhetorically, and half-jokingly: “What, did I kill somebody?” But it expands the emotional range of the song for death, and the whole darker side of life, to be incorporated into what used to be a sweet and straight love song.

More generally in Shadow Kingdom, the words are intact and the real shift is in Dylan’s vocal delivery – now a reliable sandpapery croon. In ‘Watching the River Flow’, there’s a marvellous moment:

What’s the matter with me?

I don’t have much to say.

Dylan rasps the word ‘say’ – and it feels like an old man’s emphasis somehow. This repeats more tellingly on ‘Pledging My Time’, where the word ‘time’ is given repeated aching inflection, making us acutely aware that what time means to a twentysomething, when he wrote the song, is necessarily different to what it feels like to an 82-year-old. It feels like Dylan has walked round the song and seen something else, as a Cubist painter might do.

Finally, some of the songs – as happens day in day out on the Neverending Tour – have very different melodies, and none of them is anyway near identical to what we heard on the original albums. My favourite of these is ‘Forever Young’, which has grown a descending bass line in its introduction, and has an additional gentleness to it in the famous lines: “May you build a ladder to the stars/and climb on every rung’. It’s one of two great songs about parenting which Dylan wrote; the other being ‘Lord Protect My Child’.

That song isn’t on this album. And how many people know it? How many also know ‘Blind Willie McTell’, ‘Angelina’, ‘Lay Down Your Weary Tune’, ‘Girl from the Red River Shore’ and scores of others which were deemed inadequate for album inclusion when they were written. This is the enormity of Dylan: he could record a hundred Shadow Kingdoms and we’d still need to visit them.

I don’t think this is a major album, except in the sense that everything by Dylan, being by him, is part of the gigantic edifice of his work. The slowed down songs feel more successful – especially ‘Tombstone Blues’ and ‘Pledging My Time’. In the former, I can now hear, which I couldn’t on Highway 61 Revisited (1965) that mama’s not looking for food in the alley but for a ‘fuse’. This makes for a nice full rhyme with ‘shoes’ and ‘blues’ which surround it; but I’ll always imagine her looking for a snack of some kind. The sped-up track ‘I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight’ is less successful for me, like someone trying to jumpstart a car which doesn’t want to move.

Dylan’s place in the pantheon has been secure for half a century. But he’s still in the game; who’s he competing with beside himself now? To find his equal among polymaths you have to go back past Picasso, and leapfrog your way over several centuries to Michelangelo.

This isn’t to say Dylan is flawless, or that he has ever done anything as well as Michelangelo sculpts – in fact, he’s probably the most untidy great in the history of culture. This is why there are still legions of people, with no known achievements to their names, prepared to testify solemnly that he’s no good at all. But the Australian critic Clive James was right when he complained that there’s no song where you don’t wish he’d done something differently.

But that’s because there’s never been an energy like this: already moving onto the next thing even while in execution of the present task. We have to take the greatness we get, not the kind we might have authored ourselves. Because we didn’t do it ourselves; Dylan did, and so he gets to decide.