BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

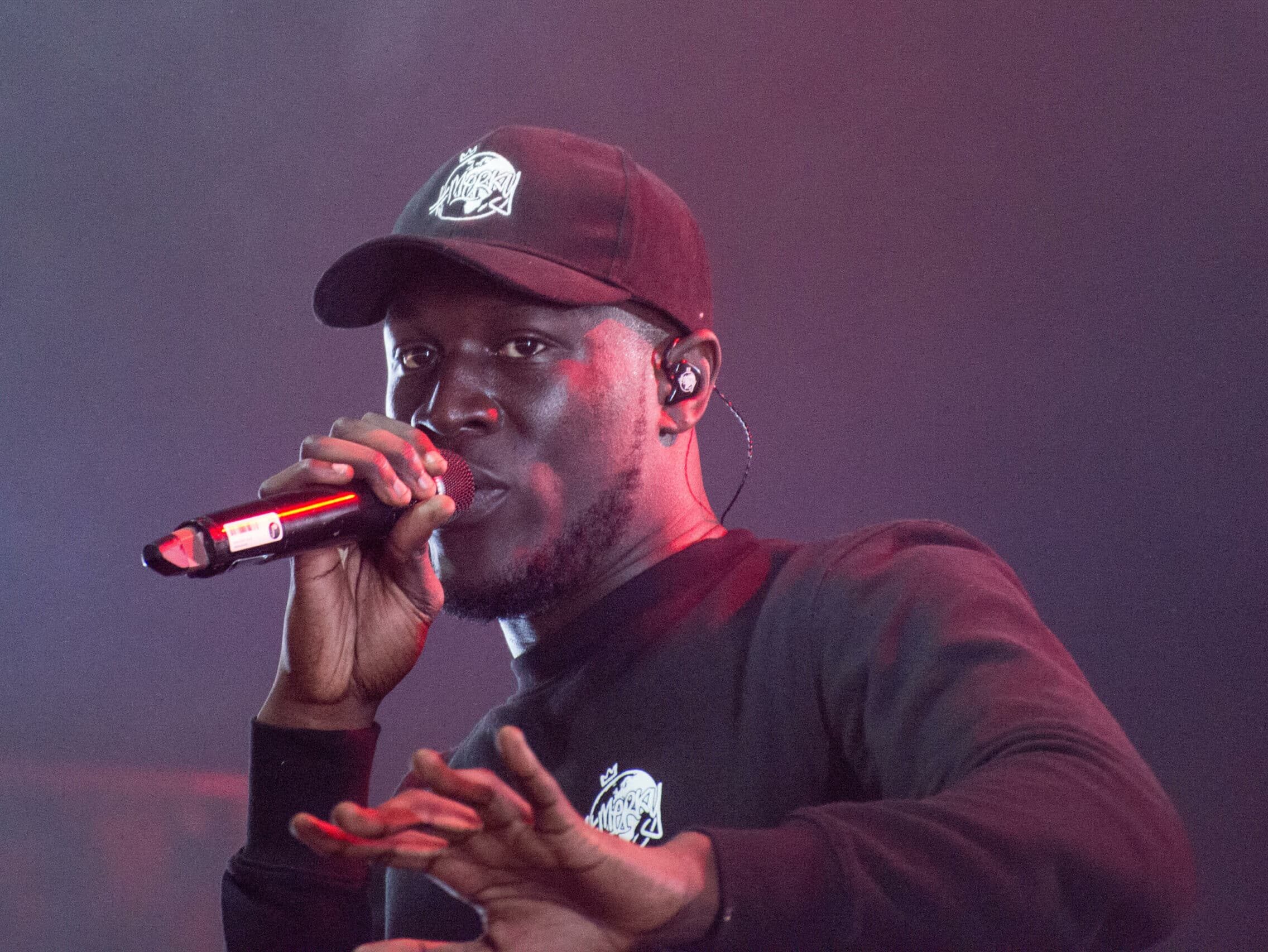

When you think of Oxbridge education, grime music probably doesn’t come to mind. However, world-famous rapper Stormzy feels right at home talking to Cambridge students and professors about his scholarship program for black students. At six-foot-five, the 28-year-old towers over the crowd outside the historic university buildings on a rare sunny day.

“Every time I see Cambridge students, I make it a point to let them know ‘you lot are sick!’ But because I’m a rapper, it can sound corny, like ‘stay in school, kids!’ But genuinely, as someone who’s tried to be one of you, it’s f**king difficult. It was so difficult, so I know first-hand.”

As Stormzy talks to the students, his respect for their achievements is clear. Growing up, Stormzy (then Michael Omari) excelled in school, earning praise from teachers and impressive marks. But, as he jokingly admits, he was also “the one to throw a sandwich at someone’s head during assembly.”

“I’ve always considered myself smart, but not arrogant,” he says. “I smashed my GCSEs, but when I went to college, I thought ‘wow, this is what it’s really like being a student.’ The transition was hard.”

Many students who breeze through early education don’t develop proper study habits, and Stormzy was no different. Although people expected him to earn a spot at a top university, he blames a lack of focus, complacency, and troublemaking for his failure to gain admission.

“I did alright at A-levels,” he admits. “A, B, C, D. At the time, I was gutted, but looking back, that’s not too bad. Then, I saw others with A*, A*, A*. When you reach that level, natural ability becomes secondary to focus, commitment, and hard work. That’s the hard part. I was naturally gifted in school, but that doesn’t work here.”

Stormzy was expelled from Stanley Technical High School after an incident where he “put loads of chairs on another student” as part of “just banter.” The administration disagreed, and just like that, his chance at Cambridge was gone. He laughs as he recalls how his perception of what it takes to get into Cambridge led him to create the Stormzy Scholarship.

“When I was younger, I thought I could come to Cambridge because I was smart. I didn’t think about anything else at the time. I wasn’t influenced by what society said. The idea of my criminal record never even crossed my mind!”

Stormzy has an admirable respect for learning. Despite criticism surrounding his public persona, it’s hard to overlook this central fact. “As much as people think rappers, footballers, and celebrities are glorified, trust me – learning, education, and reading is a much more powerful and beneficial thing,” Stormzy has said.

The Oxbridge experience has traditionally been white and male. But, along with Stormzy, Cambridge University is working to change that.

In 2018, Cambridge partnered with Stormzy to launch the Stormzy Scholarship. Initially, the scholarship supported two black students per year, covering full tuition and a maintenance grant for their entire time at Cambridge. This year, 13 students have received that opportunity. The high-profile program aims to change Cambridge’s image and emphasize that students from all backgrounds are welcome. Evidence shows that it’s working. Known as ‘the Stormzy effect,’ Cambridge has seen a significant rise in black students. Between 2017 and 2020, Cambridge saw a more than 50% increase in the number of black students admitted to undergraduate courses, along with a notable rise in applications.

Jesse Panda, President of the African and Caribbean Society (ACS) at Cambridge, is a first-year engineering student with big ideas on improving the black student experience at the university. We asked him about the so-called “Stormzy Effect.”

“I think that’s an accurate name. The support from someone as prominent as Stormzy makes black students feel more welcome at Cambridge,” Panda explains. “They see that there’s a system for them – even if they don’t get the scholarship, they know the university is making an effort to be more inclusive.”

The numbers show that Cambridge’s efforts to welcome black students are working. However, removing a centuries-long stigma remains a challenge. As Panda points out, even with record numbers of black students, white students still far outnumber them.

“The main problem is removing the stigma – the perception that Cambridge isn’t for black students. It’s still got a long way to go,” Panda continues. “I’m lucky, but I’m not as fortunate as I could be. I’m one of 180 black students, while a white student may be one of 2,000.”

That’s exactly what Stormzy aims to change. “When we first launched the scholarship, I always said I wanted it to serve as a reminder that the opportunity is there. If you’re academically brilliant, don’t think your background will stop you from studying at one of the world’s top universities,” Stormzy has said.

Panda and the ACS are working hard to show that Cambridge welcomes black students through events and outreach programs. However, due to the university’s lack of diversity, Panda understands if some black students decide Cambridge isn’t the place for them.

“We had an offer holiday through the ACS, where future students could see what the society was doing. It was more welcoming for them, showing that Cambridge isn’t just for white people – it’s for black people too,” Panda says. “We need more opportunities like that because Cambridge isn’t very diverse. The media portrays Cambridge as a place with no space for black people, but there are spaces. If someone doesn’t want to come here because of the imbalance, I understand.”

Despite these challenges, Panda remains optimistic about the future of black students at Cambridge, acknowledging that there’s still work to be done. He’s enjoying his first year, and the ACS has provided a space for him to connect with other black students and help create lasting change. However, the lack of diversity in the city is a stark contrast to his life in London.

“I think that’s always going to be there. As much as Cambridge is making progress, you still see a white environment. I haven’t been as intimidated as I thought I would be, because there are more black students here than I expected. But coming from London to Cambridge is still a big jump in terms of diversity.”

For Stormzy, the scholarship represents a symbolic continuation of his own halted academic journey. It’s a way to provide an opportunity to students he never had.

“I look back at my school years and say they were the best years of my life,” Stormzy says. “My teachers reminded me that I was destined to go to a top university, but I diverted and ended up doing music instead. I feel like I was a rare case who knew it was possible. When students are academically brilliant and getting the grades, they should know that studying at a top university is an option.”

Having risen to fame as a music star and lyricist, Stormzy’s views on education have often been sought. On one occasion, in a conversation with Charlamagne Tha God, Stormzy responded to criticism of the messages in his music: “You say, ‘Let’s learn about Shakespeare’, but Shakespeare tells stories of bloodbaths and murder, so I always say, ‘I am as positive as Shakespeare, I’m as negative as Shakespeare.’ Let’s put Shakespeare’s stories aside for a moment and go through them one by one.”

Of course, such remarks open Stormzy up to criticism. Some argue that he has a long way to go before demonstrating the nuance and poetry of the UK’s most famous writer. Others may even raise eyebrows at the comparison.

While Stormzy’s charity work is undeniably a force for good, reconciling this positive impact with the negative aspects of his lyrics can be difficult. Grime music doesn’t shy away from portraying life in underrepresented communities, often depicting crime, violence, and sexism.

Katharine Birbalsingh CBE, an experienced educator and chair of the Social Mobility Commission, disagrees with Stormzy’s influence. She believes his lyrics glorify crime and lead young people down a dangerous path.

“Some love Stormzy and other grime, drill, rap artists who are misogynistic, glorify violence, wear stab vests, etc.,” Birbalsingh tweets. “They don’t care about how it destroys the lives of boys in the inner city. Instead, they think it’s cool. Some even campaign to teach Stormzy over Mozart in schools.”

Birbalsingh later shared screenshots of a conversation with a prison officer who praised her for “exposing Stormzy as a poor role model.” The officer highlighted how prisoners often relate to such destructive media. Birbalsingh added, “Those of you promoting Stormzy have no idea of the damage you do.”

Grime music isn’t the first genre to be accused of corrupting the younger generation, and it certainly won’t be the last. Even Baroque music was initially viewed as an ungodly trend that would quickly fade.

In the 1930s, blues music was also blamed for corruption, largely due to racial prejudice in America and the fact that it was often performed by Black artists. Critics slammed blues as violent, sexual, and profane. It was even labeled “the Devil’s music.” For example, Robert Johnson’s 1936 song 32-20 Blues describes the murder of a woman who is disobedient:

’F I send for my baby, and she don’t come

All the doctors in Hot Springs sure can’t help her none

And if she gets unruly, thinks she don’t wan’ do

Take my .32-20, now, and cut her half in two’

The .32-20 refers to a powerful handgun cartridge, illustrating a violent, murder-driven narrative.

Much like the blues, grime is rooted in the experiences of the artists who perform it. Stormzy defends his lyrics’ depiction of violence, arguing that speaking about crime is far removed from promoting it. “The reason why we speak about these things is that they happen in our communities. We’re just being social commentators,” he explains. “It’s wild to blame grime music for the knife crime epidemic.”

Despite this, Stormzy acknowledges his role as a public figure. When asked if he considers the impact of his lyrics on younger listeners, he expresses awareness of his influence.

“Every time I write a lyric, I have the responsibility to tell my truth – positive or negative,” Stormzy says. “Now that I’ve reached a certain stage, I try to be more careful, but I won’t censor myself. My music reflects what I’ve lived, and I owe it to my audience to tell those stories.”

Stormzy also rejects sanitizing his experiences, arguing that his duty as an artist is to tell the truth, even if it makes some uncomfortable. “Some art should make the viewer want to look away,” he says. But as his audience has grown, so too have the complexities of being a public figure. “People don’t understand where we come from,” he adds. “Our truth is different, and I don’t expect everyone to get it.”

On the topic of sexism, Stormzy has become a trailblazer for changing the way grime artists talk about women. In 2016, before his famous Glastonbury performance, Stormzy held a Q&A at Oxford University. When confronted about the genre’s derogatory treatment of women, he had an epiphany.

“I’m sure many MCs are derogatory towards women, but we’re not as bad as the Americans,” Stormzy said. “I used to say the odd b-word or ‘sket,’ and now, hearing myself say it, it sounds bad.” Stormzy admitted his wrongdoings, acknowledging that grime often relies on misogynistic tropes, and promised to make a change.

He felt deep embarrassment when his mother questioned him about his harsh lyrics, prompting him to reflect on his music’s impact. Since that moment, Stormzy has stopped using sexist language and has taken steps to address misogyny in the grime community.

Stormzy, by Mark Mattock with art direction by Hales Curtis, 2019

The portrait of Stormzy, gazing reflectively at the Banksy stab vest he famously wore at Glastonbury, found its place in the Victorian Galleries of the National Portrait Gallery. I sat down with veteran photographer Mark Mattock, the creator of this iconic image, to discuss the process and what it means to him.

We met at The Eagle pub in Farringdon, a fitting location as Mattock once photographed food there early in his career. He shared the challenges and triumphs that led to creating the famous image. The first obstacle was scheduling, but Mattock was prepared for Stormzy’s late arrival.

“You need to expect these situations,” Mattock explains. “I knew Stormzy would show up at 3 PM, not 10 AM.”

Once Stormzy arrived, capturing the vision of the photo didn’t come easily. It wasn’t until Mattock sat down one-on-one with the artist that the piece started to take shape.

“At first, the ideas didn’t seem to come from him. It became clear that he wanted to portray something specific, so we focused on shooting him looking at the stab vest. I knew each photo would almost look identical, but there was something subliminal he was seeking,” Mattock recalls. “After a moment of frustration, Stormzy drew a square on paper and sketched himself in the frame, saying ‘I want it to look like this.’ Then we added the Glastonbury vest and other elements.”

With a clearer direction, Mattock incorporated British cultural iconography and classical imagery to transform the portrait into a thought-provoking piece, subtly addressing themes of race, empire, and royalty.

“The idea was to make it feel like a Renaissance painting,” Mattock explains. “I started with a Tuscan stormy sky and later switched to a green background—a British racing green with subliminal significance. The crown was added digitally, and we spent a lot of time tweaking the nuances to give it a painted effect. It’s actually a combination of five images.”

For Mattock, the significance lies not in the technical process, but in the context surrounding the portrait’s placement.

“I’m proud of it because it’s at the National Portrait Gallery,” he says. “It’s not just the work, but the social statement it makes. When I saw it there, surrounded by portraits of Britain’s so-called ‘greats,’ it became clear how powerful this was. The only other Black figure in that section is Queen Victoria handing a Bible to a Kenyan noble. The potency of that message is huge—it’s not a brick through the window, but it’s a strong visual statement.”

Stormzy himself describes it as “an honor” to have his portrait hung “in a gallery with so many incredible portraits of those from British history.” As a champion of Black British culture, he’s proud to see the National Portrait Gallery representing a Black artist.

“It’s not about the work; it’s about the social statement being made. That’s what I’m proud to be a part of,” Stormzy reflects.

For the National Portrait Gallery, Stormzy’s portrait signifies a shift toward a contemporary representation of major figures in British history and culture. Dr. Sarah Moulden, curator of the Victorian Galleries, explained the reasoning behind this decision.

“We wanted to represent Stormzy in the gallery after his Glastonbury performance, just before Heavy is the Head was released. We worked closely with Atlantic Records to determine the best location, and we felt the Victorian Galleries, especially the statesman’s gallery, was the perfect place for this,” Dr. Moulden says. “The juxtaposition between new and old portraits offers visitors a chance to reflect on the legacies of empire and colonialism, and the contributions people of colour have made to UK society.”

Stormzy portrait at the National Portrait Gallery, London

Mattock often discusses the painting “The Secret of England’s Greatness,” which shows Queen Victoria handing a Bible to a Kenyan noble, in reference to Stormzy’s prominent portrait at the National Portrait Gallery. While it’s not the only depiction of a Black person in the Victorian Galleries, it is the largest and most noticeable. Dr. Sarah Moulden describes how Stormzy was captivated by another portrait during his visit: one of Croydon-born, mixed-race composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor

“Stormzy and his team were drawn to that portrait,” Moulden recalls. “It’s about seeing yourself represented in the gallery. Visitors often say they don’t see themselves here, and we’ve taken that feedback to heart. Seeing Stormzy walk through and focus on Coleridge-Taylor’s portrait amidst a sea of white male figures was powerful. We may have gaps, but we can address them thoughtfully and consider diverse media.”

The portrait went on display in late 2019 and quickly attracted attention. Unfortunately, the NPG closed for renovations due to the pandemic but plans to reopen in Summer 2023.

When asked about his favorite line in his songs, Stormzy immediately highlights a line from his track “Cold”: “All my young black kings rise up / Man this is our year / And my young black queens right there / It’s been a long time coming I swear.” He reflects on the impact of this message: “I love that it resonates. With this one line, it becomes bigger than me.”

Many consider the word “rap” to come from “rhythm and poetry,” though its origins are debated. Some believe it stems from “rapport” or “repartee.” Regardless of its roots, “rhythm and poetry” offers a fitting definition. The debate over whether rap lyrics qualify as poetry has persisted. However, Todd Swift, former writer-in-residence at Pembroke College, Cambridge, believes it should have been settled long ago.

“Debating whether song lyrics are ‘literature’ or ‘poetry’ should have ended after Bob Dylan’s Nobel Prize,” Swift argues. “Now, few critics would deny the power and artistry of rap lyrics.”

So, will Stormzy be studied in the future? Swift is confident he will: “Based on the lyrics and poems currently taught in schools and universities, Stormzy is a canonical author. Why wouldn’t he be?”

Having established that Stormzy writes poetry, Swift delves into whether it’s good poetry. He analyzes the lyrics from “Crown” on Stormzy’s latest album:

Amen, in Jesus’ name, oh yes I claim it

Any little bread that I make I have to break it

Bruddas wanna break me down, I can’t take it

I done a scholarship for the kids, they said it’s racist

That’s not anti-white, it’s pro-black

Hang me out to dry, I won’t crack…

Swift sees much at play in these lines, from the mid-line caesura, echoing Beowulf, to the layers of ambiguity and religious themes. “The poem re-enacts the conflict between heavenly manna and earthly Mammon,” Swift explains, drawing connections to both Stormzy’s business and spiritual paths.

“‘Gotta stay around but make a comeback too’ is both a reference to Jesus and Stormzy’s business model,” he adds.

While not all poetry scholars may agree, Swift argues that Stormzy’s lyrics carry significant literary weight. The biblical and literary allusions demonstrate that grime is about much more than violence and drugs. Swift believes these lyrics speak directly to a post-colonial, contemporary black audience. “It’s not anti-white,” Swift points out, “but ‘pro-black.’”

Even figures like Northrop Frye, known for his literary analysis, would appreciate the depth of Stormzy’s lyrics, which engage with universal themes in a modern context. As Swift notes, the lyrics are prepared for any criticism from white scholars: “Don’t comment on my culture, you ain’t qualified.” As the poem says: “Amen.”

Stormzy performing on stage

Grime, Live!

Stormzy’s appearance on the Pyramid Stage at Glastonbury 2019 marked a major turning point in his career. Though he was already well-known, the performance is now seen as a landmark moment in Glastonbury history. At the time, Stormzy felt he had “completely blown it,” recalling the technical difficulties that left him unable to hear the sound for a while. “After about 20 minutes my sound blew and I couldn’t hear nothing… I came off stage bawling my eyes out,” he said on The Jonathan Ross Show. However, after watching the performance, he was relieved, thinking, “Thank God! I can’t believe this actually went well!”

Grime music has often been associated with controversy, particularly around its lyrics, which sometimes reference violence and drugs. In 2018, the BBC even published an article questioning if grime was “dead.” But for me and 1,999 others at the sold-out O2 Shepherd’s Bush Empire on May 11th, grime was very much alive.

I’m not a grime expert – I’m more at home with folk music and dad rock than contemporary genres. But after diving into grime music while researching for this piece, I found myself enjoying it. It became clear to me that to truly understand the genre, I needed to attend a live show. Fortunately, Tottenham-born grime artist Chip had a show scheduled the following week.

A Night at Shepherd’s Bush Empire

The Shepherd’s Bush Empire is the perfect venue for artists like Chip. It’s large enough for big names but intimate enough to feel personal. I chose standing tickets, and that turned out to be a great decision. Despite my initial trepidation, fueled by the violent image of grime music I’d read about, I quickly realized the crowd was welcoming and friendly.

The venue, built in 1903, had a charming mix of modern bars and vintage details, like large analogue clocks and signs that harken back to its history as the BBC Television Theatre. What struck me most, however, was the sheer number of people who make a live performance happen, from sound engineers to event promoters.

Daniel Maitland, a lifelong musician and teacher, offers a more realistic view of the music industry. “Most working musicians never got the capital together to buy a house,” he says. “That’s the trade-off – you live hand to mouth.” He reminds us that while pursuing music can lead to a fulfilling life, it’s not a surefire way to wealth or security.

There are many behind-the-scenes professionals who contribute to a successful concert. Live sound engineers, for example, can make up to £40,000 annually. Event promoters make around £30,000 a year, depending on experience and the venues they work with. Booking agents earn commission, often around 10-20%, depending on the size of the event they book.

When Chip took the stage, the crowd erupted in cheers. But the loudest cheer came when he revealed that his parents were in the crowd, seated in the second level. His set included older tracks as well as new songs from his album Snakes and Ladders. Chip’s energetic performance, combined with excellent sound engineering, made for a thrilling live experience.

What stood out most, though, was the strong sense of community at the show. It wasn’t about race or social status; it was about a shared love for the music.

Stories of artists like Chip and Stormzy rising from hardship to global stardom are inspiring. But is it practical or healthy to encourage young people to believe the same can happen to them?

To explore the connection between music, social mobility, and education, I spoke with Lee Elliot Major OBE, the UK’s first Professor of Social Mobility at the University of Exeter. He warns that most people don’t “make it” to the level of Stormzy. He also highlights the need for better access to the music industry for those from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“Stormzy is a great exception,” Major says. He notes that while Stormzy has committed to helping others, such as through his Cambridge scholarship, the industry still lacks enough support for young people trying to break into music. Major adds, “The dilemma for artists like Stormzy is maintaining authenticity. As you become successful, your working-class credentials can get lost. You may struggle to relate to your original audience.”

As artists gain fame, they often become detached from their roots. Stormzy, for example, has experienced moments where people were shocked by his success because of his race. He explains, “I’m going to live where I live, wear my hood up, and be in a first-class lounge… and be like, ‘Oh, you didn’t think young black people could be here?’”

Whether Stormzy’s rise leads to a disconnection with his audience remains to be seen. But Major argues that Stormzy has more influence over young people than top politicians. Reflecting on the lyrics from Stormzy’s song Crown, Major comments that Stormzy’s words resonate with the young generation far more than the political elites, who are often out of touch with everyday struggles.

Lyrics from Stormzy’s Crown resonate deeply with those from disadvantaged backgrounds: “Never had no silver spoons in our mouths, we sold (crack).”

Young people often look up to celebrities, and while this can be inspiring, it also comes with a risk. The narrative of “following your dreams” is often accompanied by unspoken limitations. Major warns against the American Dream-like narrative of rags-to-riches stories, saying, “Only a few people achieve this incredible journey.” He notes that, just like in sports, the combination of talent, hard work, and luck is not something that happens for everyone.

He believes that social mobility must extend beyond the few who make it into elite spaces like Cambridge. Instead, we need to focus on helping young people pursue alternatives like apprenticeships and local jobs to foster broader mobility.

Former Education Secretary Nicky Morgan believes that education is key to social mobility. She advocates for the return to pre-pandemic education norms and a focus on degree-level apprenticeships, which she says could significantly enhance social mobility.

“Education is one of the greatest engines of social mobility,” Morgan explains. “Ensuring that higher education is open to everyone and expanding access to apprenticeships are vital for increasing social mobility.”

The Stormzy Scholarship, aimed at promoting racial equality in education, is a step toward making higher education more accessible. However, Major and Morgan suggest that further efforts should target early education and apprenticeships. By supporting degree-level apprenticeships and underfunded schools, Stormzy could have an even greater impact on social mobility.

Stormzy at Ronnie Scott’s for the MOBO Awards nominations, 2015

The question of Stormzy’s impact is complex. On one hand, he reflects his own life and the experiences of those around him in his lyrics, which can sometimes be unsettling. Katharine Birbalsingh argues that these messages warrant a full condemnation of the artist. However, his achievements at Cambridge balance this out. While the Oxbridge experience is far from inclusive, Stormzy is breaking down barriers by showing Black students that there are systems in place to support them in what could otherwise be an uncomfortable environment.

The portrait of Stormzy at the National Portrait Gallery highlights his complexity. He is not a straightforward figure, but his influence on British culture is undeniable. Mattock and Moulden, proud to be part of this cultural shift, show that Stormzy’s portrait is more than a reflection of his success—it’s a symbol of his ability to challenge long-standing norms.

“It is clear that grime is both art and poetry,” Todd Swift explains. While not everyone will agree with comparing grime to Shakespeare, the genre clearly has a place in modern art and poetry. Stormzy’s story also highlights the gap we still face in social mobility, as both Major and Morgan point out. Without wider programs to support disadvantaged groups, social mobility will stagnate, and only a few lucky individuals will rise to the top.

To me, Stormzy is an artist who uses his platform for good. He understands the weight of his role, acknowledges past mistakes, and is committed to helping young people in the future. At 23, Stormzy has handled the pressures of fame more gracefully than many others.

A career in music is never easy, but Stormzy proves that talent, hard work, and a little luck can lead to success.

Read Stuart Thomson’s take on social mobility in the UK here