BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Cézanne is the patron saint of those who don’t find their chosen path in life easy, writes Christopher Jackson

If genius is to do with fluidity and effortlessness then Paul Cézanne wasn’t a genius at all. This isn’t meant to be derogatory to Cézanne. Sometimes in great achievement we can still see the graft that went into it – a sense that things were never straightforward, and that nothing was ever arrived at in a flash.

That kind of achievement deserves a respect distinct from the awe we feel at genius when it has less hindrance attached to it. We can see in Van Gogh and Picasso that mark-making came unusually easily to them: mistakes were simply not in their nature and that there was an unusually easy relationship between world, eye and hand which almost always added up to something worthwhile.

It wasn’t like that for Cézanne. A new show at the Tate shows how long it took for Cézanne to become Cézanne. If you’ve ever thought in your career that you have something to offer, but that it might be a long time coming to fruition, then visit this exhibition and make the artist your patron saint.

The exhibition should be viewed in tandem with reading Alex Danchev’s marvellous Cézanne: A Life (2012), now experiencing a muted 10th anniversary. This book gives vital biographical detail which the placards in the exhibition don’t have time to cover.

So who was Cézanne? Cézanne grew up in Aix-en-Provence where he would eventually die: he is one of those who doesn’t need to travel much because he suspects the substance of what he has to do lies not in travel but in stasis. To broaden the terms of reference of life would be to create an insoluble complexity; but to stay still and really pay attention might just lead you to a coup. That was the Cézanne wager.

But early on in Danchev’s biography you learn that Cézanne was defined by a coincidence: he went to school with the novelist Emile Zola. This relationship – which isn’t paramount in the Tate Modern’s exhibition – is nevertheless the chief biographical fact about him. Many people who are creative or successful are influenced to an extent they might not wish to admit by chance. For the future painter, given to a certain sluggishness, one gets the sense it was important to have the rocket fuel of a close friendship with Zola right at the beginning.

Cézanne had his influences among the dead too: Rubens, Leonardo, Puget, Delacroix. But a great friendship can be an accelerator of development and it appears to have been so in this case. It also reminds us that Cézanne’s talent wasn’t necessarily pictorial in the first instance. In fact, Zola appears to have always harboured a secret sense that Cézanne would have been a better writer than he was. Here is Danchev:

On Zola’s side there was a certain sense of inferiority, perhaps early acknowledged and then long submerged. After leaving school he dreamed of writing a kind of prequel to Jules Michet’s L’Amour (1858): “if I consider it worthy of publication, I’ll dedicate it to you,” he wrote to Cézanne, “who would perhaps do it better, if you were to write it, you whose heart is younger and more affectionate than mine.”

This is a fascinating letter, especially in light of the subsequent difficulties which would later beset their friendship. Danchev makes it clear that on Zola’s side, these feelings of insecurity were a sort of time bomb which would detonate far later with the publication of Zola’s L’Oeuvre. But it is also interesting in that it opens up onto the possibility that Cézanne’s first gift wasn’t painterly at all – instead, in the opinion of his friend, it lay elsewhere. Zola seems to suggest he was made of the sort of stuff that can turn itself to any task.

Was this true? There seems to be something in Zola’s assessment. In Danchev’s biography, we read a fascinating description of Cézanne’s attainments at school. We glimpse a general talent which would find in the end a singular outlet, and not a unique aptitude for the thing for which’d eventually become known. Danchev writes:

He [Cézanne] was a prize-winning pupil. At the ceremony at the end of the first year (when he was fourteen), he won first prize for arithmetic, and gained a first honourable mention for Latin translation and a second honourable mention for history and geography, and for calligraphy. The years rolled by in like fashion. In the fifth grade he won second prize for overall excellence (after Baille), first prize for Latin translation, second prize for Greek translation, a first honorable mention for painting…

The fifteen year old who has a first prize in Latin can be a Latinist as much as a painter later in life, and there’s always the sense in Cézanne’s life that there was something arbitrary and quixotic about his decision to be a painter at all.

But this arbitrariness itself goes into the mix and forms part of his achievement. The sense is that only someone with a certain amount of ground to make up would consider to focus with the kind of ardour which Cézanne did on just a few subjects: his bowls of apples belie a determination to really look at the world which are different somehow from Van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’, wrestled with by an artist of genius and then not subsequently returned to.

Paul Joyce, the brilliant photographer and painter, agrees with this assessment, telling me: “I think art came with difficulty to Cézanne and I have the impression he struggled a great deal with perfecting his vision. My guess is that he destroyed more work than he actually exhibited or finished.”

This is certainly the impression one gets in the Tate exhibition. The first rooms see Cézanne groping for an identity as an artist, and while this is always the case with anybody’s early work, it could be argued that the greater the artist’s eventual achievement, the more unlikely it seems at the beginning. An image like The Murder, where Caravaggio-esque lighting and the ghoulishness of El Greco’s figures combines to make an image which teaches us in one fell swoop why Cézanne would never make a drama painter. The murder in this picture doesn’t matter to the painter as an apple or a mountain would later do. Ruction and disaster didn’t appeal to Cézanne as subjects. This isn’t to call him heartless; probably quite the opposite. It might be that he felt the calamity of murder too keenly to produce a valid picture depicting it; certainly he couldn’t look at it in the same way as he would find he could look at a bather. But then, aside from a murderer, who can?

But if The Murder was a failure of sorts, it was a promising one. Crucially, it must have been sufficiently promising to Cézanne, since he kept going. This fact alone is a reminder that perseverance is rarely rational: without it, nothing would ever be achieved. Persistence needs to be innate: if we weren’t wired to dream, few would rationally continue with their first efforts, since in the ordinary scheme of things these tend to be extraordinarily unpromising.

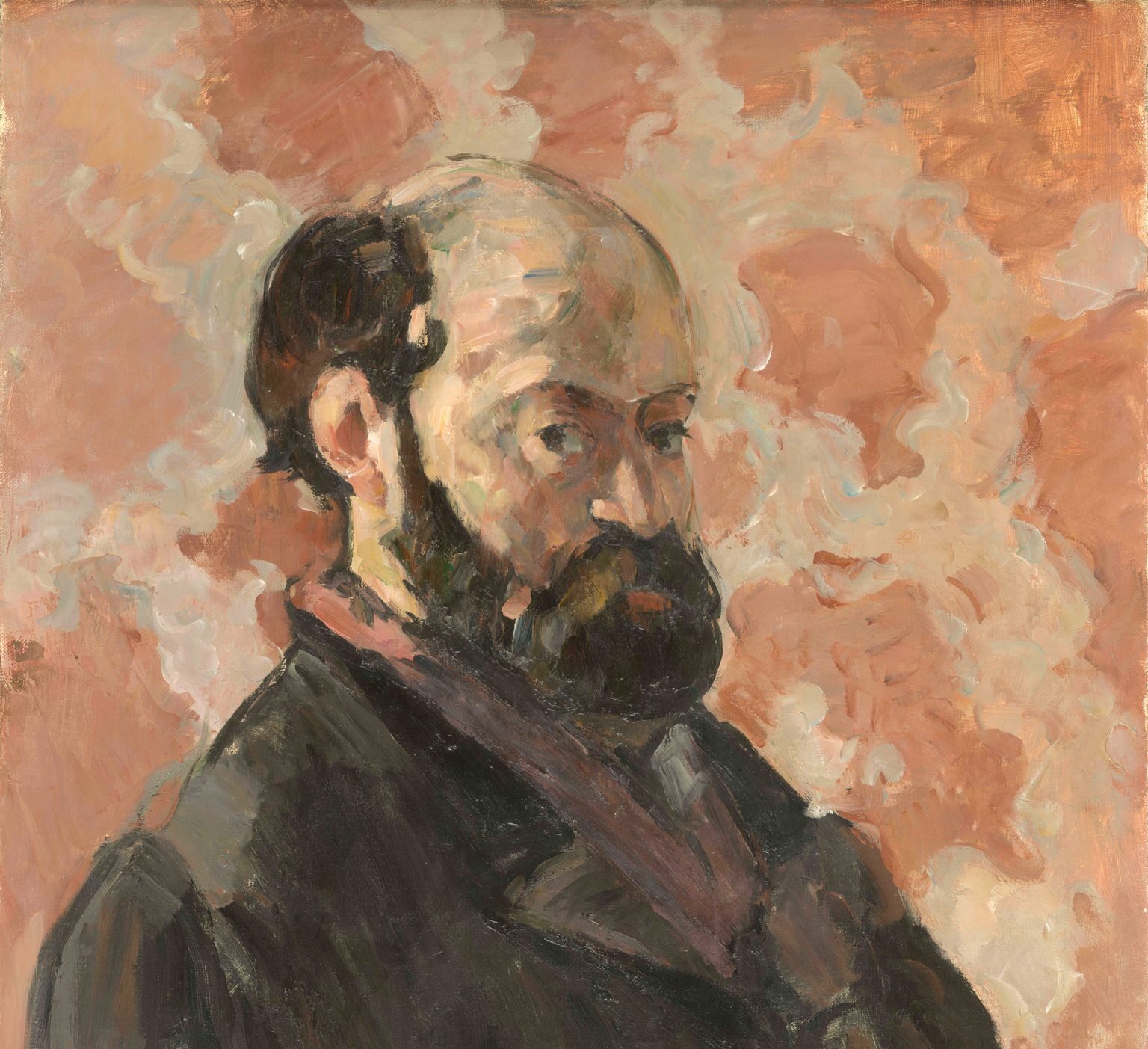

Success, then, is often against the grain. At the Tate Modern, a self-portrait of Cézanne against a pink background dating to 1875 seems to contain this knowledge. The colours of the face are applied with a delicate care which reminds you of the fragility of any human face, composed of little strokes which happen to be together, and which might just as easily rush apart. The eyes, tired as if with too much looking, also seem vulnerable: ambivalent about the tasks ahead, doubtful about the likelihood of self-fulfilment. It’s an arresting intimate image, bringing a fragile ego near. This portrait might give us our own permission to make inroads in our own lives, since we can see that one of the great names in history didn’t always seem confident of his value.

John Updike once wrote a review of a Jackson Pollock show which began very unpromisingly and then transformed itself in round about Room Three, with the advent of the famous drip paintings. “Beauty, how strange to find it here!” Updike exclaimed in that article. One wants to exclaim the same in the Tate exhibition as the exhibition ripens in its last rooms.

By this point, Cézanne has found his subjects: bathers, Mont Saint-Victoire and of course his famous apples. When I ask Paul Joyce what he has learned from these masterworks he replies: “There are really too many lessons to learn from Cézanne to simply list, and as you return to him and his work as your own career as a painter progresses, you realise that what you may barely grasp from him is that the closer you look, the more you see. Colour, balance, fluidity of brush stroke, command of the subject, ability to build “atmosphere” and movement into a still, flat canvas amongst many more things.”

That’s a good summary of what these last rooms offer. One might add that Cézanne, though he looked hard at the world, always looked with a consciousness of the limitations imposed on looking. A humility pervades his work, which is a possible reason for his popularity today. It is the genius as everyman, which makes us wonder if mightn’t we be great too.

His popularity may be set to grow again. Cézanne lived without too much pizzazz, and may therefore be an attractive figure in our own cost of living crisis. Danchev cites some evidence that the painter came to feel that his friend Zola, showered with plaudits in Paris, had come to live too grandly. Cézanne never did that; his was a quiet existence dedicated to work.

Nevertheless, though Zola is less admired today than Cézanne, this work ethic was an example which he had had all along from Zola himself. The novelist wrote to Cézanne when he was 21 that ‘in the artist, there are two men, the poet and the worker. One is born a poet, one becomes a worker.’

To some extent, Zola heeded his own advice: his complete works comprise a formidable number of volumes, most of them fat. He might be one of those writers who makes shelves groan more than he makes readers dream. The friendship between them reminds us that work for its own sake can lead to an inferior achievement: sometimes it can really be volubility. It was once said in relation to Proust that a bore is someone who tells you everything, and perhaps Zola was a bit like that.

In relation to Cézanne, one senses a greater focus – a more coherent and patient mindset about the task which needs to be accomplished. This had also, to an extent, been pre-empted by Zola who wrote to his friend in 1877 regarding his work: “Such strong and true canvases can make the bourgeois smile, nonetheless they show the makings of a very great painter. Come the day when M. Paul Cézanne achieves complete self-mastery, he will produce works of indisputable superiority.’ Though this might have been to damn him with faint praise, something like this prediction did in fact come true.

What was that legacy? Cézanne realised his own way of looking. Too often we tend to think of him as a staging-post in the history of art, but I don’t think this is quite right. All artists worth their salt do something unrepeatably unique. Too often, we compare them to those who came before and after, meaning we don’t properly take the measure of what’s in front of us. Maybe this is especially a problem with Cézanne, not only because he really does have antecedents and a legacy, but because something about his pictures feels hard to rise to. There are those whose opinion one respects, who would say: “Oh God, not another Mont Saint-Victoire”. We feel we cannot match his intensity and so we turn away.

What is his art ultimately about? The great landscapes flaunt the strokes by which they were compiled and yet each individual stroke which seems so apparently simple, adds to the alchemy of the whole. This art then comprises more than just a series of fragmented strategies: they’re shot through instead with honesty about our predicament as creatures dwarfed by the scale and complexity of things. That means that his landscapes and his apples are really unusual kinds of self-portraits because they are as much about the insecure position of the painter – and his integrity to admit that insecurity – as they are about the mountain or fruit which he is ostensibly depicting.

Van Gogh’s condition as a genius likely suffering from bipolar disorder was always impinging on his work. Cézanne was saying something else: that we’re all standing on shifting ground. It’s the kind of thing which, once said, has to be admitted by everyone. This accounts for his influence, and this has carried into the present day. There is some anxiety attached to high achievers: we think we might not be able to outdo them, and feel our own efforts likely to be paltry when set next to theirs. One can easily guess what Cézanne himself would have made of such a defeatist attitude. He would have liked the mantra of Sir Kingsley Amis: KBO (Keep Buggering On).

Paul Joyce tells me: “Artists are always anxious whatever their reputation or state of maturity may be. Each generation is influenced by the previous one and the History of Art is simultaneously one of constant homage and theft. My answer would be “be anxious, be influenced, then set out on your own path, like Cezanne!”

It’s sound advice – and you don’t need to be a budding artist to heed it.