BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Christopher Jackson never set out to interview celebrities – but over the years he’s learned some lessons the hard way

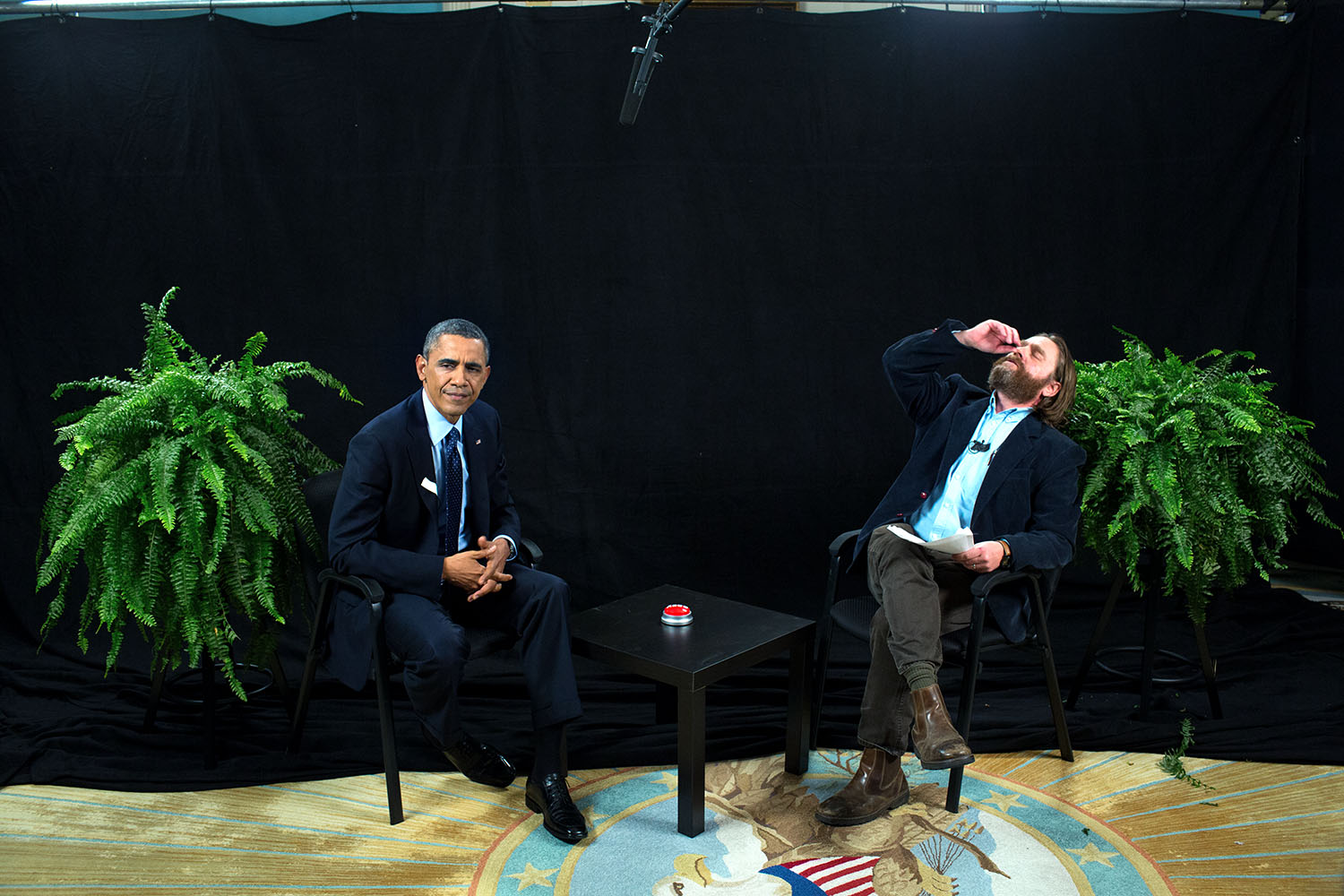

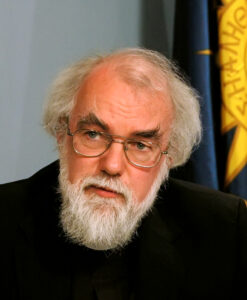

I remember the week I met Sting was the same week I met the then Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams. It was to be a lesson in the strange quirks of the celebrity interview.

I arrived in Cambridge to meet Williams, and walked past Pembroke to the Master’s House. The door peeled back and there was Williams, at least a foot taller than me. At such times, one feels slight bewilderment at the accuracy of television, together with something else: a vague sense of what it doesn’t tell you.

In Williams’ case, the famous face was here, assembled in the atoms of reality more or less exactly as the pixels of my television had done so for me before. But there was something else here: a nervous energy which I hadn’t been expecting at all.

In time I would discover a very simple explanation for this: Rowan Williams was worried because he anxious about missing his train to London. A certain realisation would follow from this: that an Archbishop of Canterbury worried about being late for his train strongly resembles anyone else worried about being late for his train.

But Williams was polite. I remember a high hallway, with a horizontal balcony beyond it hinting at recesses of space. The setup was too cerebral to be called luxurious but there was an undeniable sense in which one could see that being the Archbishop of Canterbury is a solid career move.

Over years of doing these interviews, I’ve been struck by the little details. Seeing Rowan Williams preside over Easter in a cathedral, one doesn’t necessarily think of him owning a Nespresso machine. But I happen to know he does.

The interview went fine, though Williams was evidently anxious due to the fact that he was worried about being late for a talk he was scheduled to do at the British Library. Trains do not wait for Archbishops of Canterbury. When I got him to sign one of his books which had once been my grandfather’s, the Archbishop’s desire to be rid of me was both palpable and understandable.

A few days later, it was snowing in Battersea as I presented myself at the 16th floor of Sting’s apartment. I knocked on the door and it peeled back to reveal a long dark corridor and a sense of unexpected hush.

Somebody with a clipboard went past me and said nothing – exactly as figures sometimes do in dreams. I was sent through to a kitchen where not one but two private chefs were rustling up for Sting and Trudie what looked to be a Michelin-level dinner.

They also said little, and I began to fear that I had entered a regime whereby everybody was terrified of speaking in case Sting flew in in some kind of temper.

I needn’t have worried: in fact, Sting and Trudie were doing a radio interview in the living room. While I waited, I studied the pictures which seemed to be of industrial sites in the north.

Then I was ushered through to the living room to find Sting and Trudie, as with Williams a few days before, looking awfully like themselves. There is a level of wealth nowadays which leads to multiple houses across various continents. In Sting’s case, there’s the Battersea house, the main house in Wiltshire, an apartment in New York, and a gorgeous Tuscan house: Villa Pallagio.

The existence of an extensive property portfolio can sometimes create a sense that none of the properties are really being lived in, and perhaps the Battersea apartment had the impression of a work in progress.

The long parquet floor had a triple aspect view of Putney to the west and Parliament to the East: there was an exercise bike on the balcony which you can still see from the train on the journey from London Victoria to Denmark Hill.

But Sting himself had a certain rooted energy which made me think that he has in some way more internal power than Rowan Williams. This might perhaps be because trains – or more likely private planes – do wait for Sting. He has more money and can arrange his life around his moods. The rest of us, whether we preside over high-profile Eucharists or not, have to fit in with National Rail and the M25.

But there was something else too: an inner confidence which had to do perhaps with being ratified over and over again by the world but to have retained a soul somehow. This is a difficult achievement and I have seen it from time to time.

In the years since I have sometimes said to people that talking to Sting was like interviewing an oak tree. Afterwards, he showed me the apartment, and then explained the photographs I’d seen in his kitchen. He said they reminded him of growing up in Newcastle.

You have to remember this when you meet well-known people: they have their backstory, which, except in the case of Royals, is usually a time when they weren’t famous. In a way your job as a journalist is to access that person – that essence. It has to do with what they were before celebrity came to them, which may be something they’re trying to be again now that everybody knows their name.

Writing Cricket Bats

All of this is what makes journalism such a curious job: it opens up onto such curious juxtapositions, of peculiar doors opening. Sometimes they open in a strange order which can feel designed to tell you something.

Looking back over the early part of my career, it would have all seemed very surprising starting out. Perhaps that’s partly because the wish to write and the wish to be a journalist are often separate wishes. Many writers get sidetracked by journalism – and some get sidetracked again into PR and never really write what they suspected they had in them.

Others fail to get sidetracked and never earn a penny and so get discouraged and oddly protective of their unpublished masterpieces. As usual some sort of middle ground is probably best: you need to find your way while also retaining some core sense of what needs to be written by you, for the simple reason that it needs to be written and nobody else can write it.

For young writers generally, probably at some fundamental level you simply want to write. That is an ambition to be respected within oneself, but often its provenance and even its meaning can be very vague. It leads to a series of questions. Write what? Write, how exactly? Every day or just when the mood takes? And also when? Am I ready yet? Do I need more life experience? For so many writers, the answer they arrive at in relation to the question of when can be an all perennial: tomorrow.

The answer needs to be: today. How do you learn to write a novel? The answer is so banal as to seem almost absurd. Try writing a novel again and again and again until you know how.

But journalism I think is different. It isn’t only to do with oneself and the keyboard. It comes instead with all the institutional structures of magazines and websites: editors, magazine staff, circulation, reach, clout, costs – these are parameters, and parameters might be deemed limitations.

That’s because they open up on to the very important question of who will actually be prepared to talk to you. This will be determined by your usefulness to that person – and that will be determined by brand, audience, and sometimes personal connection.

It can be a chicken and egg problem for a new magazine. If you happen to be running a magazine like this one, then your magazine will claim more readers if famous people will talk to you. That’s partly because of the largely regrettable fact that we live in a celebrity-obsessed era.

I never particularly planned to interview celebrities. It comprised no part of my motivation to begin writing. I was interested in poetry primarily – the sound of words.

I felt a jolt of recognition when I read Henry’s speech in Sir Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing:

This [cricket bat] here, which looks like a wooden club, is actually several pieces of particular wood cunningly put together in a certain way so that the whole thing is sprung, like a dance floor. It’s for hitting cricket balls with.

If you get it right, the cricket ball will travel two hundred yards in four seconds, and all you’ve done is give it a knock like knocking the top off a bottle of stout, and it makes a noise like a trout taking a fly. What we’re trying to do is write cricket bats, so that when we throw up an idea and give it a little knock it might travel…

I still think that’s sufficiently true to be worth quoting at such length. Stoppard was someone who I’d interact with a bit – and I would have pinched myself then if I’d known how that would go.

But always for writers there’s the question of money. This simply isn’t true for, say, people with a deep hankering to be a lawyer. In such blessed instances, it’s understood that money will take care of itself. In writing, that’s not the case: unless you can be the first person to come up with a YA novel with a bespectacled wizard called Harry, money categorically will not take care of itself. You could commit to a lifetime of writing cricket bats if you wanted, but would anyone pay you for it?

But they’d pay you for journalism – not very much, but maybe enough. And that was something – and it was that which led me to the celebrity interview.

Ray of Light

I remember my first assignment which had anything to do with celebrities. It was a somewhat bizarre event at the Sanderson Hotel behind Oxford Street. It was sponsored by Rolls Royce who had taken it upon themselves to create an occasion whereby new models had been made and matched to an existing rock star.

I didn’t quite understand the concept – and still don’t. But my then editor noticed that two of the celebrities were Roger Daltry and Ray Davies and I was sent down to try and get a diary story out of it. Diary stories are perhaps the hardest form of journalism insofar as you are likely to go to great lengths to secure a mere eighty words. I’ve known people who did the diaries for the nationals week in week out, and never understood how they didn’t go mad.

I remember as I arrived I was walking next to the hotel and noticed someone coming up behind me walking faster to me and to my left. I turned around to see that this rapid walker happened to be Roger Daltry himself. Nowadays, knowing it was a press event anyway, I would state my name, and politely request that I might ask him a few questions. If he said yes, I’d try and keep him talking for as long as possible. Who knows maybe I might make a feature out of it.

Back then, in my salad days, I wasn’t sure if that was appropriate. Which is why I find myself years later writing an article to tell young journalists not to do what I did: journalists must learn to be unabashed and realise that they have nothing to lose. I seem to remember I grimaced out a smile and said nothing: the exact opposite of what should be done. In reality one should just ask: very occasionally, a celebrity will be unpleasant. Usually they’re not – and always they’re just people, even if they are.

A few moments later, a car pulled up and Ray Davies, far more infirm than I had expected, sort of hobbled out. Daltry, who clearly knew him, said: “Is this guy the future or what?” It was a lovely thing to witness the laughter and the electricity of it all.

But I remember looking past Davies at the crowds of people watching him, and thinking: “But they have their lives too? Who decided these two were important and the rest of us not?” The answer to that is that nobody in the immediate vicinity besides Davies had thought to write and perform ‘Lola’ and ‘Waterloo Sunset’.

But I still think there’s something in the thought. Who knows what people are really like on the inside anyhow? It might be this which caused the great philosopher Maurice Nicoll to call life a drama of visibility and invisibility. I heard years later that Davies wasn’t always nice to people he worked with – and I feel sure that when it comes right down to it, his celebrity is no excuse for that.

But that electricity stayed with me – and of course I had a story to tell friends and family. I still think that the fun of it all is a joyful aspect of doing celebrity interviews – but it is also something to be wary of. As the years went by, I began to meet people who were either well-known in their industry, and sometimes those who were well-known nationally – and then, though not all that often, those who were known the world over.

An early insight came doing legal journalism. It was Jean-Jacques Rousseau who claimed that if we were able to look into the heart of mankind, we’d more often want to travel down the scale than up. Rousseau was seeking to idolise the poor and as was so often the case with him, he had things completely the wrong way around.

I remember one of my early roles was to interview those exalted lawyers who argue regularly before the US Supreme Court. Without any exception, they were polite and delightful to talk with. But it was also my beat to cover the East Midlands market for debt recovery – a far less rarefied world. And there I did sometimes meet with surliness.

John Donne observed that sometimes riches and fame are a sign of some sort of bestowed blessing: we shouldn’t, he argued, go around demonising the rich. Maybe they’re rich for a reason.

Of course, it’s not always so simple as that. Over the years it’s seemed to me that celebrity confers an enormous opportunity for the enactment of good deeds and noble purposes. Of course, it also contains a sort of temptation: if you’re well known you can usually get away with being fairly awful, and we’ve seen some of those people flushed out by the #metoo movement.

But in the happier first category was Andre Agassi, one of the greatest of all tennis-players, who I met at Wimbledon one year.

It was a bit of a journalistic jamboree. Sometimes, very well-known celebrities will try to deal with their press in one big go, and on such occasions, sometimes you and about 30 others are given 10 minutes with a star. It’s easier for them that way.

That was the case for Agassi whose reason for being had to do with an agreement he’d reached with Lavazza coffee. Lavazza would support Agassi’s education initiatives on the West Coast of the US, and in return he’d do a day for them at each of the major tennis tournaments.

The trouble was that Lavazza had just launched its new range of coffee cocktails: something to do with coffee, gin and champagne. I was told Agassi would be there in half an hour, but in the end he was three hours late.

Soon, I was four or give cocktails down. I suspect Agassi must have wondered when he met me who this red-faced and strangely confident journalist was. I seem to remember I in fact forgot to press the record button at the start of the interview. “Hey, man, is that even recording?” asked Agassi. Then we began laughing, and fortunately the wonderful photographer Graham Flack was over the other side of the room to catch the moment of realisation.

That turned out to be an education in transcribing your interviews as soon as possible, or at least uploading them to the cloud. A few days later, my recording only half-transcribed, I was at my niece Georgia’s second birthday party around a pool. I watched her with interest and then with mounting anxiety from the other side of the pool as I saw it occur to her that she could swim without armbands.

Needless to say she couldn’t, and when I jumped in to pull her out again in all my clothes, I had forgotten to take my phone out of my account with the Agassi interview on it. Young journalists beware.

The Rise of the EA

But what mattered then was that I could see Agassi was a kind man, determined to use his fame to help with the educational needs of people from impoverished backgrounds.

Sometimes, of course, a celebrity will do a lot of good very quietly, as the world discovered after the death of the late George Michael. Michael was compulsively kind – and he had the money to enact his kindness.

I would say that on balance over the years I’ve been pleasantly surprised by the people I’ve ended up meeting. There was one mega-famous TV star who has a saintly reputation who turned out to be rather rude, and then was rude to a member of my editorial team, as if to confirm to us that he really was that way.

But in general, I’ve found the staff that crop up around well-known people more difficult than the celebrities themselves. There was the impressive and formidable henchwoman of a former prime minister, who asked for about five exploratory calls before the interview only to raincheck for vague reasons.

Then there was the right hand man to an internationally famous actor who was in an almost permanent state of crisis. Before interviewing his boss, I had arrived at the conclusion that he was destined to be terrifying and had braced myself for some sort of grilling, and even wondered whether the interview might lead somehow to my death.

He turned out merely to be very particular, but at heart kind beyond expectation. What had happened was that his EA had got himself into a state about things potentially happening which didn’t bother his boss in the least.

Still, all these bodies around a well-known person can be bewildering to comprehend. A filmmaker friend of mine once worked with Robbie Williams. I asked him how it was. He said: “The trouble is that Robbie Williams can’t walk in any room without being flanked by seven other people.”

My friend pointed out that the difficulty is in actually talking to Robbie while simultaneously trying to figure out who all these other people are.

But looking back, the most wonderful thing is when you get to meet or interact with your heroes. Two of mine were Clive James and Sir Tom Stoppard.

Clive is no more now, and it was a bit of a race against time to get to interview him for The New Statesman towards the end of his life. Clive was in many respects a changed man by the end, humbled by media exposure over his extra-marital affairs.

I made sure I asked the right questions, and even permitted myself slightly longer questions than usual, though I subsequently edited out my bits, reasoning that the reader would be far less interested in my questions than in Clive’s answers.

This meant that to interview him was to have a sort of brief tango together – tango being the dance he most loved. I was delighted when afterwards I received an invitation to his house to the launch of his last epic poem The River in the Sky.

Sadly I couldn’t go as I had committed to a press trip with my family and wrote a poem about my predicament. Years later I got to tell Douglas Murray about this, and received his kind amusement at the poem. “But you should have sent it to him!”

Murray incidentally was less famous than he is now, but delightful to talk to for around three hours. He was also one of those people I met too early as I didn’t fully understand the importance of his work – as he could almost certainly tell. But sometimes this is preferable to not meeting people at all. Journalists may end up cringing at interviews, but overall to fear cringing is ultimately not to live fully and so one is better off risking an encounter you feel you might not be up to, and learning to live with your mistakes. Cringing is to do with a pride we’re still feeling now: journalists need to get over that – as we all do.

I think about his comment about my Clive poem sometimes – and it reminds me that after the Rowan Williams interview I walked around Cambridge and found myself next to Clive’s house. I stood briefly outside; it was just another house on just another street. But it was special to me because Clive wrote what he wrote in it.

We meet each other so fleetingly here – one’s journalistic career seems to be full of strange fragments like a dream. Sir Anthony Gormley using the word ‘orthogonality’ at an interview at the First Site Gallery in Colchester. Henry Blofeld forgot his hat and I ran out to give it him; he gave me that grimace we do when we’ve forgotten our hat and will likely not see again the person who’s just restored it to us. Jonathan Agnew, whose wife had recently recovered from cancer, was very kind when he heard about my own wife’s MS. When we went our separate ways he said: “Now look after yourself” in a way which struck me as very kind.

Sir Tom Stoppard and I had a few emails over the years – his kind and fascinating, mine overly voluble. My publisher and I decided that since I was talking to him I might ask him for an endorsement for my book An Equal Light. I wrote to him at what I now think of as ridiculous length that I was rather embarrassed to ask for an endorsement. “Don’t be embarrassed, let me be that,” came the lovely reply. We worked it out in the end – and the endorsement we ran mentioned Clive.

Overall, the celebrity interview has its pitfalls: you mustn’t become a namedropper – and I say this knowing that for many years I definitely was, and of course, have had to be so again in order to write this article. And perhaps that’s another lesson – it’s fun to namedrop a little bit, provided you never think that by meeting interesting people you’ve necessarily become more interesting yourself. You may, in fact, have become a bore without realising it.

But in general, there’s a binding fragility about us all, which we saw at the start of this year with the fires in Los Angeles. When you meet someone you’re meeting them in time, their time ticking at the same pace as yours. In fact, it is an astonishing thing to find oneself occupying the time of someone well-known – entering their story, when they had already entered yours by their deeds. There’s a privilege about it all which makes it worth its while if your career happens to go in that direction.