BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

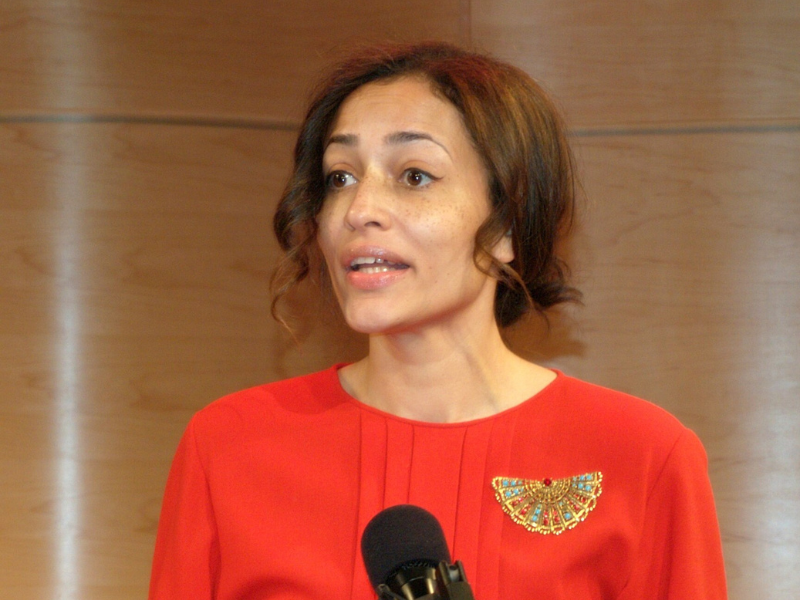

Zadie Smith

One morning recently, I opened the internet and saw an extraordinary painting by Tracey Emin of the Passion. It’s in the Royal Academy and has rave reviews, but the review said: what could be more shocking than a painter like Tracey Emin painting the Passion?

That got me to thinking of when I was a baby writer. I remember reading these lines by Foster Wallace: “If you worship money, you will always feel poor. If you worship beauty, you will always feel ugly. If you worship power, you will always feel weak.” I remember thinking: “If you worship God, what will you always feel?”

When I wrote White Teeth (2000), the comedy of that book was that there were two groups of religious people — Muslims and Jehovah’s Witnesses — and then a third set: liberals. The joke was that the third set thought they didn’t have a religion, but they did. That’s what interested me, and it’s partly because I grew up in radical atheism. Once, when I was about nine, my boyfriend bought me a Bible for my birthday, and my mother threw it out of the window in front of his face.

But looking back, I never lost my interest in religions as philosophical systems. I was fascinated by people breaking fast, and seder — I was always intrigued by religious solemnity of any kind. After White Teeth, I wrote The Autograph Man (2002), which is about Judaism and Buddhism. My third novel On Beauty (2005) is about the worship of art. Then there came NW (2012), which for me is an Anglican novel. Swing Time (2016) is about a syncretic African idea of the world, where many thought systems merge. To me, The Fraud (2023) is a Catholic novel.

Having said all this, and having written all these books, I’ve realised, after 25 years of work, that if writing is a way of being good, then it’s a very slow process. This is a very laborious way of becoming a slightly better person.

At NYU, I would meet truly evil moral philosophers, selfish poets, or brutal novelists — and I include myself in that last category. I thought: “This doesn’t work. Look at all these people — and look at me.” When I moved back to London, to the same street I was born on – living now in the nice house, and not the council estate across the road – I was again surrounded by Jews and Muslims and Catholics. Like the Jews, I don’t have heaven and hell; like the Muslims, I believe in surrender to contingency; and like the Anglicans and Catholics, I find the story of Christ inspiring. And like the Hindus, I have many gods.

There’s a local church in my area, and it’s the church I used to dance in when I was a kid — a big 19th-century church, and half of it was sold off to flats around 1987. I found myself going one day and I walked in, feeling very nervous. The congregation, on a good day, is 12 people — half of whom are heroin addicts. The first day I walked in, the vicar didn’t come — and one of the congregation, a homeless man, was giving a eulogy for for his dog. I thought: what am I doing here?

I think I had an alibi in my mind — an Iris Murdoch alibi. I think, to me, the idea that God exists universally and in every culture is God — and that is what interests me. It’s still an alibi — but on that occasion, it led me to a situation where I was in an Anglican church worshipping an Alsatian.

I still go. Every Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, we feed people in the community. When I walk through the neighbourhood, I now think: that’s not a meth head, that’s Dave. I see every layer of my community — because I know these people now. It’s that thing: how do you want to be connected with people? It’s also about being in a place where, for thousands of years, people have gathered to be quiet. I suddenly found that a not-contemptible idea.

The language of Anglicanism is meaningful to me — and the whole conception of prayer has interested me more and more. I’m not in any way an effective, good, or faithful Anglican, but I was so interested in the idea that this space — in a world dominated by contemporary capitalism — is not available anywhere else.