BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

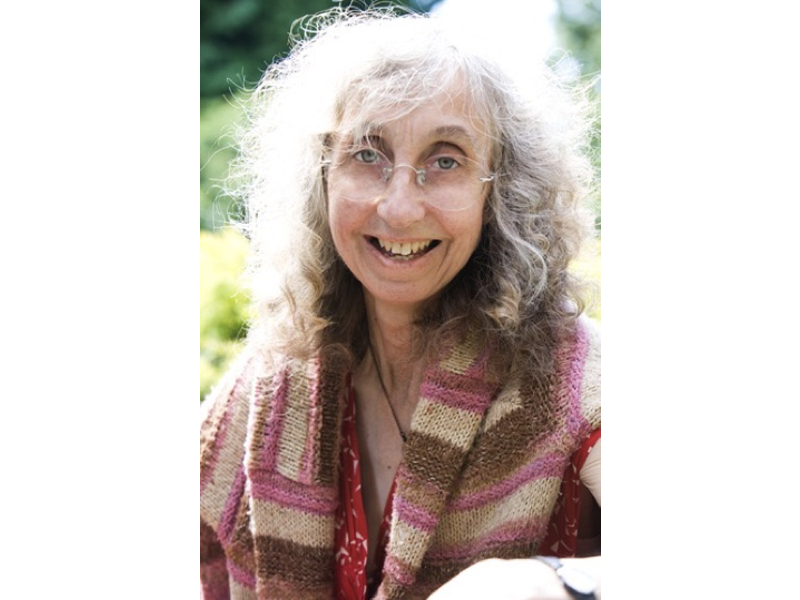

As part of our regular series which looks at the relationship between poets and the workplace, Alison Brackenbury discusses her how she has managed to juggle the need to earn a living with her commitment to her art.

Alison Brackenbury has had an unusually interesting working life. She won a scholarship to Oxford and left with a First in English. She subsequently married and moved to a small town in Gloucestershire, where she combined writing with horse-keeping, parenthood, grassroots politics and a variety of non-academic jobs. For twenty-three years, until retirement, she worked as a manual worker and bookkeeper in her husband’s family metal finishing firm.

Her poetry shows deep respect for tradition. It has a worked-at burnish and commitment to form which reminds us of manual labour. Brackenbury is a maker, too worldy-wise not to know that a poem must reach as wide an audience as possible. There is a streak of pragmatism in her poetry, which sits alongside – and is perhaps fed by – a rare knowledge of nature.

For Finito World, she has produced an exceptional poem ‘Metal Finishing’ which illustrates her many strengths: impeccable technique; a knowledge of the real world; the quiet humanity of her noticing. Above all, we always feel that Brackenbury, like Larkin – another poet who did actual jobs – understands that if poetry is to have any place at all in our busy lives it must be memorable.

And that, more often than not, will mean that it will rhyme. But the point is that it is an insight that could only have been arrived at by her having once been busy herself. Brackenbury is a great advert for the idea that in order to write you first need to have done jobs.

Metal finishing

Nobody worked like the West Midlanders.

I scrambled off my bike from one sharp frost

to find a driver dozing in his van.

God knows when he set off from Birmingham

to have his tooling first in Monday’s queue,

be ‘Just in Time’, words spat by me and you

as by steamed vats of acid or oxide

we plated, coated, fought off rust, then dried

laser-cut tools in our Victorian mews.

‘Like Dickens!’ grinned the driver while he chewed

three o’clock lunch, then roared down our back lane.

We quit. Accounts and knees reported pain.

Small margins were not hard to understand,

for decades, we wired robot parts by hand.

There was untarnished love in this, no doubt.

Our buildings saved us, sold, walls razed, dug out.

Milk bottles crash. I wake. It must be four.

I listen while the van throbs from our door.

Notes about the poem

Metal finishing: processes which protect metal from corrosion. I worked for 23 years in a tiny family company which spent half a century battling with rust.

Just in Time: a production system in which manufacturers do not hold stock. Components are delivered by sub-contractors, ‘Just in Time’. It was not popular with metal finishers..

Finito World: Metal Finishing is a wonderful poem. Whenever I read your poems I always feel: ‘This is someone who has done something else in their life other than poetry.’ Did your career empower you to write?

Alison Brackenbury: I think that my work – especially in industry – gave me material for poems which is rather unusual in British poetry. For example, there may not have been too many poems in the Times Literary Supplement about a van driver’s narrowly averted industrial accident…

I have always had paid jobs which had no direct connection with poetry. This did make me aware that many people are unacquainted with or even frightened of poetry. This strengthened my own desire to write poems which attempt to be as musical as possible, and relatively clear. There’s always room for a little mystery!

Conversely, what role did your love of poetry have in giving you confidence in the workplace?

Like many people – perhaps, especially women? – I have had to be pretty pragmatic about what I did, simply to keep the financial show on the road.

I have had three, very varied main jobs. When I ran a technical college library, I was regarded (rather optimistically) as a source of knowledge about literature and poetry. There was (then!) just enough spare money in the budget to buy a little poetry. I was amazed and pleased to find one day that a young woman police cadet had plucked a copy of Wordsworth’s poetry from a display and was reading it aloud to some remarkably meek male colleagues… In a public sector admin. job, I again had a rather undeserved reputation as an expert on literature and language. When consulted on knotty points of grammar, I would point out blithely, that poets simply dodged such issues and wrote something quite different, invented if necessary! In my hectic industrial job, few of our sixty customers knew that I wrote. But I was sufficiently fierce about language to be unimpressed by various waves of fashionable phrases, used in larger companies. Privately, I always referred to ‘Just in Time’ as ‘Just Too Late’. Post- Brexit, I fear that this international supply system may be ‘Much Too Late’…

The government has recently said that poetry should be optional at the GCSE level – a significant demotion in its importance on the curriculum. What is your view on that and what do you feel the impact will be?

I have great admiration for teachers, but I’ve never taught, and my daughter is now in her thirties. So I don’t consider myself an expert on poetry in the curriculum. But I do know that many people ONLY know – and value – those poems which they encountered at school, especially if they learnt them by heart. If they don’t come across poetry which appeals to them in their curriculum, the one chance may be gone.

What poetry should be on the curriculum? I can only offer three observations. First, having to study one set text which is the work of a single contemporary poet may have the very unfortunate effect of turning many pupils against that poet! I’ve heard this widely reported from university lecturers, who find that most of their students are prejudiced against the major living poets on their former school curriculum. Secondly, I think that the subject matter of a poem may be more important than its period. My daughter reported from her (very mixed) comprehensive that the boys in her class were truly impressed by the poetry of the First World War. Finally, I think there is a case for studying an anthology – possibly a themed one, with poems from various periods? There’s a better chance, in that variety, that a student will find one poem whose sense speaks to them, and whose music stays in their mind.

Was there a particular teacher when you were younger who turned you onto poetry?

No, although I did have some very good teachers who introduced us to a range of work. I remember poetry books being available to read in the later years of primary school. I discovered much! But I could have been put off poetry for life by my first class in that small village school. Our (untrained?) infant teacher used the dullest doggerel I have ever encountered. I don’t know where she found it. I dreaded those afternoons.

What’s your favourite poem about the workplace?

‘A Psalm for the Scaffolders’, by Kim Moore. It’s a compelling – and fiercely humorous – account of a dangerous, skilful job. Technically, the poem is entrancing, with its repetitions and powerful beats: truly, a modern psalm. Kim is much younger than me, and has so far only published one collection. She is a poet to listen out for – and she had her own skilled previous career, teaching children to play the trumpet.

I can reveal, after hearing her read, that the man who fell thirty feet (and lived) is her father… Here are the scaffolders: