BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

Paul Joyce

If I were to introduce myself to you as a gambling man, then I would be willing to bet you a pound to a penny that your reaction to the statement I will shortly make would be one of the following: a) a sharp intake of breath; b) a quick gaze heavenwards; c) a short swearword or lengthy blasphemy d) “You’ve got to be kidding me!” or “thanks for the warning!”.

So here we go: I am about to present my credentials to you as a reviewer of the latest releases of classical CDs, and I do not read a single note of music. There, and yes that’s indeed what I said, and once the smoke clears I will try and explain why I still feel this is a task I am not only willing to do, but possibly well suited for as well. Oh, and by the by, I worked alongside the wonderful opera director Jonathan Miller (on his mighty BBC Shakespeare series, and as his assistant on his final La Boheme at English National Opera) and he couldn’t make out a single note of music either!

Despite the fact that my prep school instilled in me a dread of music classes where small groups of children wielded reedy recorders to little visual or certainly audio effect, it was only a little later when I attended Dulwich College that one of those legendary teachers (we can all name one) provided me with a proper introduction to the language of Music. And here I really do mean Music with a capital “M”, and as to its unique language, for surely it is the only one that speaks without the need to master a foreign tongue (of which there are over 7000, I am reliably informed, spoken and signed.)

Once played and experienced, its universality becomes immediately understandable, and most significantly, a direct means of communicating all important human emotions: joy, sadness, pain, loss, regret, nostalgia, sentimentality, but above all (and this is why I own three thousand CDs), pleasure. In ideal circumstances a musical fanfare would announce our birth, then marriage, together with many highlights in between, and some previously selected individual track {“My Way”?} would finally see us into the oven or the ground. In other words, although we rarely think of it as such, we spend much of our lives within a musical envelope of some kind. Yes, even in the now infamous lift, so thoroughly despised by composer Peter Maxwell Davies (muzak, that is).

My job now is to help those of us with a traditional bent towards classical compositions, but who do not have a sea anchor to cling on to, to appreciate the wealth of recording both existing and yet to be laid down, which hopefully will now start arriving on my desk every month. I hope too that you will learn to trust my judgement, at least in part, flawed though it may be considered in certain circles, in at least dividing wheat from chaff. At the end of the year I will compile, like the venerable “Gramophone” magazine, a list of what I consider to be the finest new (or re-issued) recordings. Believe me there is a deep vein of musical masterpieces waiting to be mined, recorded and re-recorded, and then humbly presented by me for your future enjoyment.

I am thrilled to be asked to reach out to you every month or so with my strongest and best recommendations, and in return would urge you to communicate your own thoughts and experiences within the contemporary classical music market place back to me; for it is one which has regained its strength, curiously aided by the individual isolation during lockdowns, and is now thriving in a way unseen for some decades. I also have some tips on how to obtain CDs even on a tight budget. What I will not be able to help with, is the matter of streaming and downloads. I’m afraid I am locked into the notion of physicality of what I own, which is why I quickly abandoned Kindle nonsense and returned with a sigh of relief to my modest library. Who would have thought that expensive reference-quality vinyl pressings would be walking off the shelves, along with first, HDCD (High Definition Compact Discs) then followed shortly thereafter by SACDs (Super Audio Compact Discs). Sound frequencies are being captured that defy the human ear and only bats in belfries would understand. Enough of these boring technicals, so now, music maestro please!

David Fray is a comparative youngster (born 1981) at least compared to other older and possibly more easily distinguished pianists. He burst onto the scene in 2008 being named as Newcomer of the Year by BBC Music Magazine, and was immediately snapped up as a potential star by Virgin Classics. (Although Warner Classics now seem to be releasing his recent albums). Already his collaborations have involved many of the most prestigious names in the classical music scene; conductors Marin Alsop, Kurt Masur, Riccado Muti and Christoph Eschenback amongst others. Thus far he has recorded Bach, Mozart and Schubert and it is his interpretation of the latter’s works that I want to comment on today.

David Fray

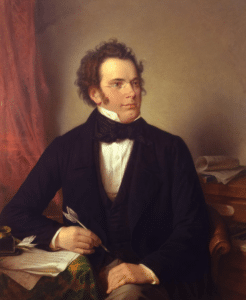

I will return to Schubert (1797-1828) quite frequently I suspect in this column, as he ranks toward the top of my “favourites” If not actually planting his flag on the summit already. Other contenders would of course be that legendary lion, Beethoven, carefully guarding the gates to a musical nirvana, with Mozart closely behind and Dvorak managing a spirited sprint towards the finish line. And with dear Franz who died at the frankly ridiculously early age of 31, we encounter, especially in his piano work, a soul-searching and maturity quite belying his few years on earth. It is funny (strange) how, if one survives long enough oneself, that likes and dislikes, passions even, come and go with the passing decade. For instance, when I first read Ernest Hemmingway’s “Across the River and into the Trees” in I guess what might have been my early twenties, I thought it immediately a masterpiece. Returning to it in my forties I considered it to be a cliché-ridden tract of an old man with nothing left to say. Now, as I exceed the age of the dying hero in this wonderful novel, I come back to hailing it as a much underrated masterpiece again. In other words, our own unique experiences in life mounds the way we respond to the world’s ability to wound us or transport us in the most unlikely ways. (Remember it was Hemmingway who said that one becomes strong in the broken places.) So it is with Schubert’s sublime sonatas and moments musicale. These seem to me to be the pinnacle of a genius who understands that ultimate sadness, and feeling of reluctant surrender to the enfolding arms of inescapable loss that we all experience as we trudge towards that inevitable darkness; the big sleep. At a later date, as I say, I will try and summarise my view of the great Schubert pianists, Radu Lupu, Sviatoslav Richter, Wilhelm Kempff, Imogen Cooper, Paul Lewis, Maurizio Pollini, Alfred Brendel, Murray Perahia , Mitsuko Uchida and many more dead and alive. No barrier to age or sex, each brings his or her individual talents to bear on Schubert’s timeless music.

Franz Schubert

So now to young (ish) David Fray, and I will discuss and address his two Schubert recordings which I note are about seven years apart (2008-2016). Fray approaches Franz with a deal of caution, which I feel to be only appropriate. Comparing Fray’s interpretations of say the moments musicale 1-6, with one of the piano’s grand masters, Wilhelm Kempff and his recordings stretching as far back as the 1960s, the timings between the two are completely different. In each case, Fray is drastically slower, in one case up to nearly three minutes behind Kempff, and the longest of moments is only just over seven minutes! Now there are musicians in the past who have seemed to wilfully adopt much slower musical tempi than others (including often the composers themselves) such as Otto Klemperer for example. And it is true that other great conductors, and here I am thinking particularly of Toscanini, have set records in brevity.

Thus, I am reminded what Sir Thomas Beecham quipped when questioned about the speed he adopted in a final concert piece, so saying “that’ll get the buggers home!” Sometimes speed can generate a direct emotional response in an audience, for example The legendary Hollywood Quartets’ version of Dvorak’s American Quartet, in my view the very best available. Something is clicking in my memory that Bernstein laid down a Mahler symphony where one movement doubled in acknowledged length in his hands.

But I digress, back to Mr Fray. He clearly divides critical opinion. At a live recital at Wigmore Hall more than a dozen years ago the Guardian critic Andrew Clements wrote: Fray certainly looks the part: bent low over the keyboard as if intent on drawing something personal and highly wrought from the instrument. But the slackness of his playing and its strange discontinuities were far from convincing…..and a little later in summary: Some fierce, almost brutal octaves in the finale of the Waldstein seemed surreally out of context, like a sudden fit of temper. Perhaps Fray was as disappointed with his performance as some of the audience. Hardly a ringing endorsement. And here is Hugo Shirley in “The Gramophone”: Fray’s approach is supremely seductive but it does occasionally sound as though he’s about to nod off… Well I would certainly not go that far but there is a tendency of his, in my view, to over-extend notes and chords to a point where some would find more than a hint of sentimentality emerging.

However, if I have to deliver a verdict on his Schubert, I think it is masterly, imaginative and the occasionally extended time he takes strikes me as being entirely in concert with the music itself. This to the point that, when I returned to old favourites (as in the list above) some sounded frankly hurried and pedestrian. Although in relation to my own age, many would assume any vote from me would go to Kempff, in fact my own X rests firmly on David Fray’s forehead, surrounded by his beguiling Franz Listian locks.

I shall be scouring the record label’s catalogues for upcoming new releases from Fray, whose talents at the keyboard stretch over many compositional centuries and musical styles. But I have a feeling that he is far from done with Schubert, and personally I can’t wait to hear his interpretation of the three final sublime works of Schubert’s genius, piano sonatas D958, 959 and 960.

Paul Joyce is an internationally renowned director, painter, photographer and writer.