BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

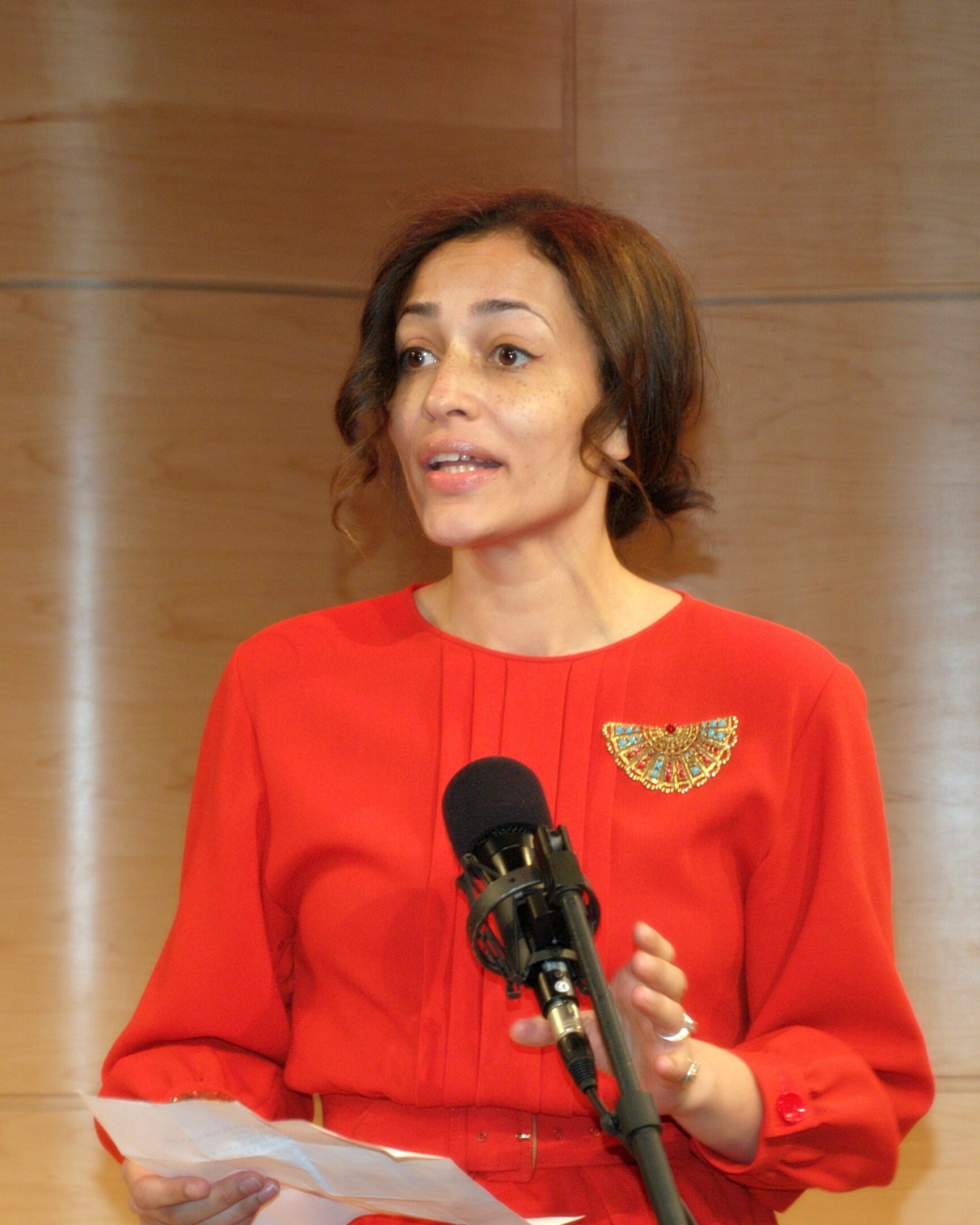

The great writer on why the dialogue around universality has shifted

For the past few years, I’ve been reading about Simone Weil with the idea of writing a novel about her—a great ethical thinker, a socialist, and, of course, a Catholic. There’s an essay I return to yearly, Human Personality, in which Simone considers what a truly afflicted person might cry out in their affliction. Not someone suffering a microaggression or merely offended, but someone truly afflicted.

She notes that one possible cry is: “You have no right to do this to me.” Weil is interested in this sentence because it draws on the discourse of rights, a concept she traces to Roman property law—usus, utendi et abutendi—the right to use and abuse what is yours. That very discourse, she reminds us, was once used to defend slavery among the Romans.

But Weil is searching for a different language—one not rooted in property or entitlement. She argues that the true cry of the afflicted is: “What you are doing to me is not just.” That cry, unlike the first, is not individualistic. It is universal.

So one question worth asking is: where does that language still live? I can think of three traditional places.

The first is faith. In this space, we hold that human beings are sacred because God created them. But of course, that language is often abused. Think of someone like JD Vance, who seems to suggest that the sacredness of the human increases with their Americanness or proximity to his own identity.

The second is the language of human rights, formalized after the disaster of the Second World War. We might ask what kind of disaster it takes for people to rediscover the human, to speak of humanity again.

The third place is literature. Here, the particular is used to express the universal. As a young reader, I spent all my time in this realm, in that belief system. You could say: “I too am Madame Bovary” or “I too am Leopold Bloom.” But for someone like me, the complication arises: I could joyfully participate in that universal, but could someone like me be the universal for someone else?

That became my project when I was twenty-three: to write novels in which people like me could be universal, too. I’m a comic novelist. I write funny books, mostly. In them, people meet across borders and build friendships. When I used to read those novels aloud, I did all the voices—I’m from a family of actors and performers. That’s how I grew up.

But 25 years later, although I still write novels about people encountering each other across lines, I no longer do the voices aloud. And why? Because the discourse around particularity and universality has changed. To do all the voices now is to risk being accused of erasing them, owning them, speaking over them. The entire literary conversation has, in many ways, been submitted to the framework of rights.

Each novel, one way or another, has become an expression of the rights of a particular group. That’s not a critique—because to get rights in a democracy, you often must first appear as a specific group. But the other language—the one that allows for solidarity—has started to vanish.

The late Pope Francis saw this clearly. He notes how technology plays a role: it promised us a total indexing of human experience. Everything became categorized, including people. Literature, in many ways, surrendered to this system—like the indigenous people lying down when Columbus came ashore. It submitted to this taxonomy.

Yes, many extraordinary novels have emerged from this period. But now the question remains: is there still a language for the universal? I don’t think it can be the language of the 19th century. There’s no point resurrecting that novelistic form. That human subject is gone for most people.

So the challenge is: what kind of novel might yet speak anew? How do we find a new foundation for the human—one that avoids nostalgia, and instead creates a space for solidarity, for the universal cry: “What you are doing to me is not just”?