BBC News

BBC NewsBorrowing was £17.4bn last month, the second highest October figure since monthly records began in 1993.

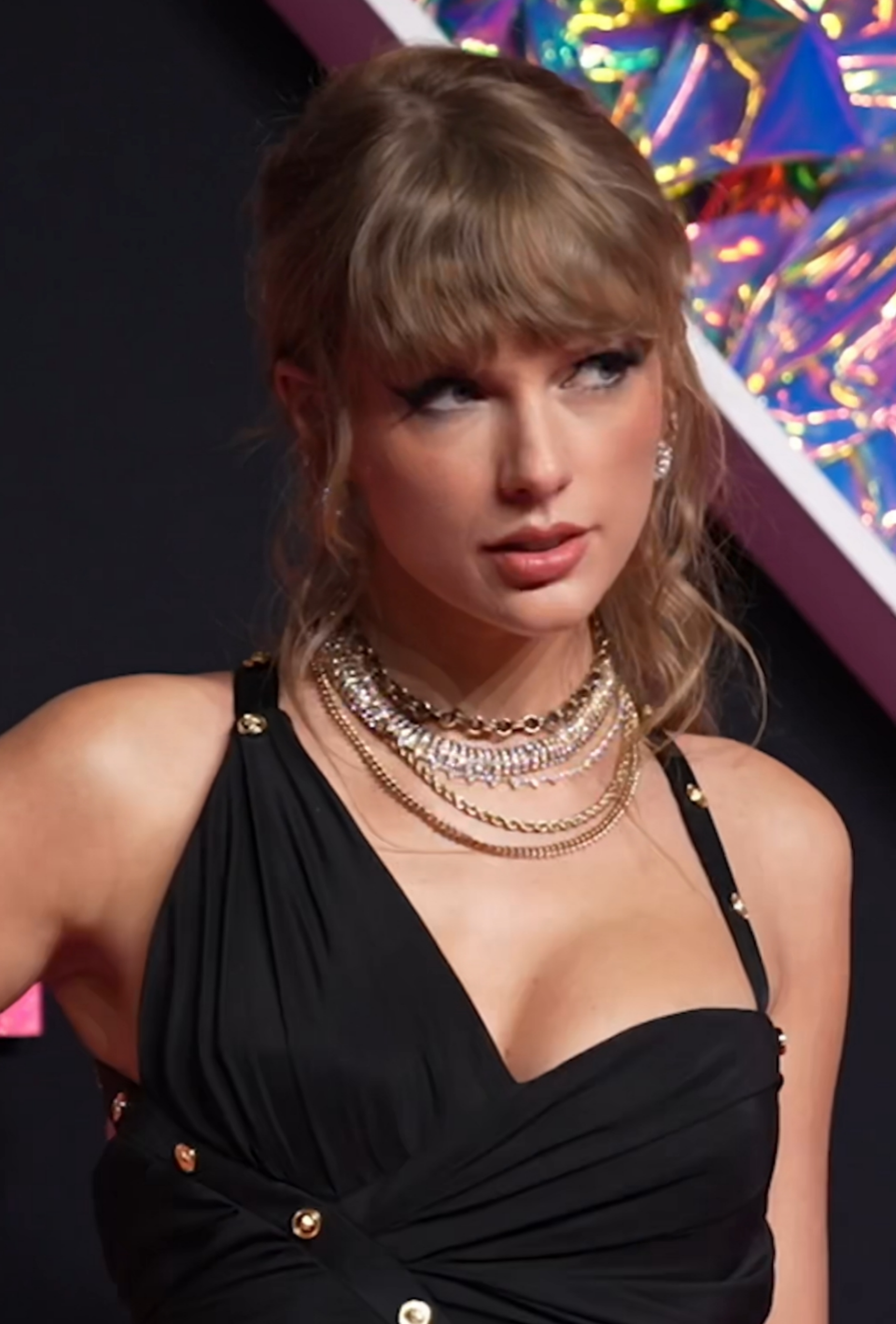

Christopher Jackson interviews the course convener of the new Taylor Swift course who tells us how he became a Swiftie – and why the singer is worth studying

Popularity and cultural importance and not always attributable to the same things. Bob Dylan is plainly popular and culturally important; Queen were popular but not necessarily important in quite the same way. Similarly, a whole range of unpleasant people become culturally significant, from Aleister Crowley to a range of unlovely politicians, without being in the least bit liked.

The question of Taylor Swift has partly become so gigantic because there is a growing consensus that she seems to be both. Some are in denial about this: there are still people prepared to say that her phenomenon is somehow the product of a gigantic misunderstanding and that her essential talentlessness will reveal itself in time. But they are in opposition to a growing number of devotees who now include Prince William, Sir Paul McCartney and Hugh Grant – and millions of others.

One thing which happens when you’re culturally important is that the universities begin to take you seriously, as they have long done Dylan, culminating in that Nobel Prize for Literature in 2016. Whether Taylor Swift will one day get the call from Stockholm remains to be seen but the ground is already being prepared. Dr Andrew Shields is the co-convener for a course in Taylor Swift studies at the University of Basel, and has worked at the university for 29 years. He tells me about his journey towards becoming a cerebral Swiftie.

What is it that makes people sceptical as a lyricist of talent arising out of her particular milieu? “If people are treating her as someone who comes from pop, there’s some sort of history to the idea that popular music doesn’t have much going for it in the way of lyrics. But the actual milieu which Taylor Swift emerged from is country, and that all has to do with storytelling – and storytelling was one of the first things I noticed about her.”

So when did he first hear Swift? “The first song I noticed was when a friend of mine played a cover of it at a gig in Switzerland in 2012. He played ‘We Are Never Ever Getting Back Together”. I didn’t know it was by her but I saw immediately that it had brisk and vividly sketched characters.”

A few years passed until Shields’ next encounter with Swift. “Later on, one of my daughters showed me a video of Swift’s song ‘Mean’. Recently I stumbled on how she said that the grain of sand that catalysed the song was a particularly nasty review of her performance at the Country Music Awards. I was bullied at school and so I like an anti-bullying song. Later when I stumbled on ‘Blank Space’, I came to understand that she was writing fiction. Even in songs where you think she may have just sat down and versified her biography, even there, there’s still fictionalisation.”

I ask him if any specific lyric struck him. “In her song called ‘Mine’ there’s this amazing line: ‘You made a rebel of a careless man’s careful daughter’. Today, when Swifties ask me what my favourite line is, which happens a lot, I say I will tell you the song, and you have to guess: they know immediately which line it is.”

So how did the course itself come about? “By the time Folklore came out, I was on the way to being a Swiftie – I like the way that album has much more space. There’s room to think and make the music meander. I also noticed there were many more good lines in that album. When I got the email last year as to what I wanted to teach in the spring, I said maybe Taylor Swift, and then the email came back: “Great idea.”

So did Shields and his co-convener Rachael Moorthy need to advertise the course? “I had to write a course description and that was posted in December in the list of courses.” The interest was immediate. “Some were Swifties who said: ‘This is awesome’. Others came to us and said, ‘I’m not an English student, but can I take it?’ We reached a peak where 180 people had signed up for the course, and we had a room originally for 90.”

The course itself looks at Swift purely from the literary criticism perspective – it doesn’t cover her exceptional business decisions down the years. “People said to me, ‘You’ll be able to explain why she’s such a megastar!’ Well, she writes good texts and that’s an explanation!” Shields says.

So how is the course structured? “Throughout the semester, we address one album per week, after an introductory session on Swift’s early song ‘Tim McGrath’. That seminar was about rhetoric and ambition, and Rachael spoke about her song ‘The Lakes’ where she described the relationship between that song and the Romantic poets’.

In one interesting week, Shields landed on perhaps Swift’s most famous song ‘Cruel Summer’. Shields recalls: “I picked that song because of the line: ‘What doesn’t kill me makes me want you more.’ I ended up talking about aphorism. That’s because Swift is here playing with a Nietzschean aphorism. I then talked about how her texts themselves become aphorisms out of which her fans make new aphorisms by playing with them.”

For Shields, the way in which these songs have entered our collective consciousness and then been toyed with by us all, is testament to the quality of the work. “The way the Swifties work with the language shows the quality of her texts – and the quality of her writing does play a role in the sheer scope of her success.”

This scope is indeed extraordinary and at time of writing seems to know no particular bounds. So what will students who take this course go on to do careers-wise? “People who study English in Basel often end up as High School teachers,” says Shields, “but I also have a whole bunch of former students who are journalists.

Two of the people who interviewed me this term about the course were former students. Others also go on to fill roles in the HR space. We also have a lot of psychology students take the course who now get the chance to see what it’s like to delve into literary texts as literary scholars and push beyond and really leave behind the issue that it must be because people can identify it that’s what makes it good.”

What is wonderful about talking to Shields is his sheer enthusiasm, which is a lesson in itself about how we learn, and we decide to with our lives. It is one, of course, shared by Swift – and by all those who achieve success in life.